Stirring memories, savoring tradition

Celebrating a mother's culinary legacy through the flavors of the past and the warmth of home-cooked traditions

For Dr. Lydia Rodriguez Arcellana, the holidays were never about the twinkle of lights, festive music, or the bustle of commercial festivities. Instead, they were defined by the aroma of home-cooked meals, turning her childhood home into a culinary haven.

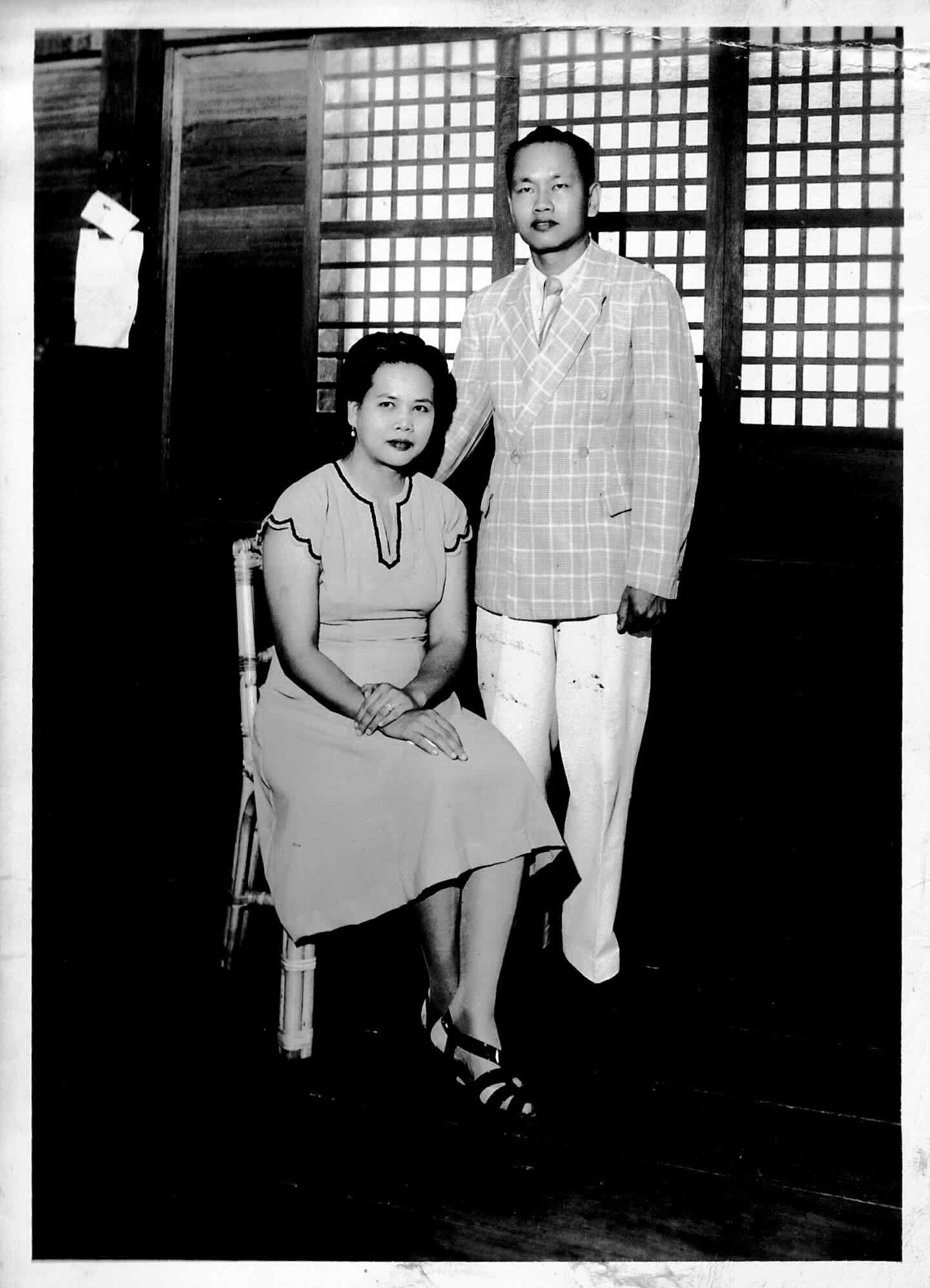

Now retired, Lydia, former professor at the University of the Philippines Department of English and Comparative Literature and one of the pioneering graduates of its College of Mass Communication (1966), carries a dual legacy. Beyond her academic contributions, she treasures a collection of Tagalog recipes passed down from her mother, Inocencia Tanchoco Rodriguez.

“My mom was an excellent cook, the best in the family,” Lydia recalls. Inocencia’s culinary reputation reached across family ties, drawing relatives from the Tanchoco clan in Nueva Ecija and the Rodriguezes in Malabon to her table.

Studying at Centro Escolar de Señoritas (now Centro Escolar University) in the 1930s, Inocencia balanced her training as a pharmacist with an innate gift for cooking. Her creations relied on instinct rather than recipes, her skill honed through years of practice.

“She would listen to the bubbling of the stew,” Lydia explains. “If the bubbles were slow and deep, she knew it was time to add the next ingredient or adjust the heat. It was like a symphony, with her as the conductor.”

Crafting edible masterpieces

Among Inocencia’s celebrated dishes was rellenong manok. Lydia vividly describes her mother’s precision: “She would carefully cut around the bones, peeling the meat back without breaking the skin. It was like watching a surgeon at work.”

The chicken, meticulously deboned, was stuffed with a mix of ground pork, chopped vegetables, breadcrumbs, raisins, hard-boiled eggs, and spices. Once reassembled, it was both a visual marvel and a culinary delight.

“It was magic,” Lydia says. “She made it look effortless, but the skill and patience it took were extraordinary.”

Another hallmark of Inocencia’s repertoire was tinumis, a tangy blood stew distinctive to Nueva Ecija. Unlike the richer dinuguan common in other provinces, tinumis offered a lighter flavor, with sampalok (tamarind) as the souring agent instead of vinegar.

“She never measured anything,” Lydia says. “She would taste and instinctively know what to adjust.”

Among her other specialties were Russian salad, a potato salad with carrots and red beets; paksiw na pata with banana flowers, a dish made with pork legs; and adobong palaka, or frogs’ legs, accompanied by a rich chicken asparagus soup.

A holiday tradition

In Lydia’s family, Christmas was anchored by halayang ube, a purple yam dessert her mother made exclusively for the season. Preparing it became an annual ritual.

“She would buy kilos and kilos of ube from her suki at the Malabon market,” Lydia says. The process began with peeling and grating kilos of yam using an aluminum grater reserved for the occasion. Her father, Dean Feliciano Roxas Rodriguez Sr. of Mapúa Institute of Technology, often joined in, stirring the thick mixture over a low fire.

The result—a creamy, velvety halaya—was presented in crystal bowls, becoming the centerpiece of holiday gatherings. It was proudly shared with neighbors and friends, earning praise from Lydia’s aunts as “Halaya ni Ateng yan (That’s Ateng’s halaya)!”

Preserving a legacy

Though Lydia’s career left little time for mastering her mother’s kitchen techniques, the early lessons stuck. “Cooking back then was

an art form,” she reflects. “It took time, patience, and meticulous effort.”

Inocencia’s insistence on fresh ingredients and traditional methods resonates today, particularly with the resurgence of sustainable practices, farm-to-table movements, and slow cooking.

“She would love how people now are rediscovering the beauty of cooking with intention and care,” Lydia says. “The way chefs and home cooks celebrate local, organic ingredients feels like a return to the roots my mother cherished.”

In honoring her mother’s traditions, Lydia keeps her family’s culinary heritage alive, reinforcing food’s role as a cultural treasure and a means of connection.

For Lydia, her mother’s legacy lives on in every carefully prepared dish and the memory of a kitchen filled with sounds, smells, and laughter. A bite of halayang ube or the tangy notes of tinumis transports her to a time when the holidays were more than a celebration—they were a testament to the irreplaceable warmth of home.