A buzzword has re-emerged—and captured—the attention and imagination of many Filipino economists and public intellectuals: “industrial policy”. Understandably so; our case of industrial failure is a remarkably exceptional one, even by the standards of developing countries.

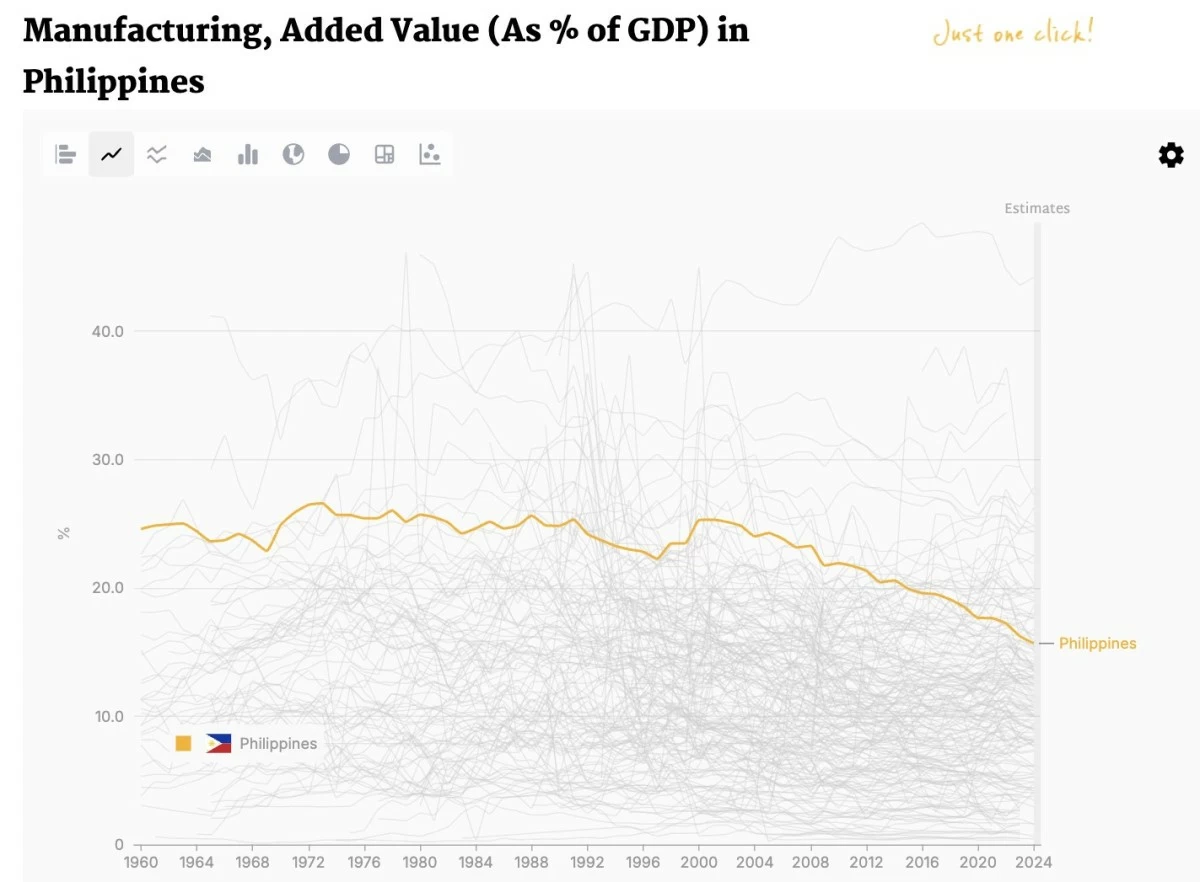

In 2024, manufacturing accounted for merely 15.7 percent of our GDP—an all-time low—dismal compared to the all-time high of 26.6 percent in 1973. It is also the lowest among our neighbors (Thailand at 24.9 percent, Vietnam at 24.2 percent, Malaysia at 23.0 percent, and Indonesia at 18.7 percent). This figure alone, setting aside nationalist sentiments, paints a stark picture of why a clamor for industrial policy exists. Industrial policy witnessed a global resurgence as an instrument for development, partly because of the successes of the East Asian “tigers”. This recent revival has been famously articulated by UCL professor Mariana Mazzucato, who reportedly met privately several weeks ago with Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim to discuss “green investment, technological innovation, and digital transformation” in Malaysia.

In recent weeks, the term has been frequently (and often loosely) invoked by our media-savvy political analysts. While their diagnosis of our economic problems often appears compelling, we must proceed with extreme care when discussing the cure.

This is not to say we should abandon discussions on industry or manufacturing. On the contrary, understanding the mechanics of a competitive manufacturing base is a necessary undertaking. It is sound economics to analyze our structural weaknesses—asking, for instance, why our electronics exports generate limited domestic value-add, or why our agro-processing remains fragmented and unscalable.

However, recognizing these structural flaws and labeling them as grounds for a Mazucatto-styled "industrial policy" require further examination of the term.

To demonstrate why this leap can be dangerous, we must clearly differentiate between two vastly different approaches to ‘industrial policy’: (1) general (or "enabling") and (2) targeted (championed by Mazucatto). General industrial policy refers to broad-based assistance that applies equally to all businesses and industries to free up space for greater competition; it focuses on leveling the playing field through free trade policies, property rights protection, broad-based deregulation, tax simplification, and support for basic public goods like R&D, innovation zones, and regulatory sandboxes. In stark contrast, targeted industrial policy means exactly what it implies: the government actively picks winners and losers in the market by utilizing targeted loans and guarantees, selective tax breaks, trade protections, corporate bailouts, regulatory privileges, and noncompetitive contracts.

The danger arises when analysts advocate for the latter. Targeted industrial policy calls for active state intervention to shift resources into specific sectors it deems “strategic”.

This is a massive leap in logic: it is the difference between saying “we need better infrastructure” and decreeing “we will subsidize a national steel industry.” For the ordinary Filipino, the absurdity of the government picking such ambitious goals is obvious just by looking around. Targeted industrial policy requires immense, almost flawless bureaucratic competence. Yet, we are expected to trust that a state incapable of efficiently running a single-line metro rail system (where “single-line” and “system” already feel like an oxymoron) will somehow successfully execute a complex industrial policy, one that supposedly leads us to the heights of artificial intelligence, chip manufacturing, and complex materials processing.

To paint a clearer picture, let’s look at one historical example: The Progressive Car Manufacturing Program (PCMP). Launched in 1973, it was the quintessential attempt to legislate a targeted industrial policy. The strategy was to select five “winners” (including Ford and Delta Motors/Toyota) and mandate that they use locally made parts like tires, batteries, and glass. The intent was to create a robust ecosystem of Filipino suppliers. But in reality, the program ignored the fundamental law of manufacturing: economies of scale.

In auto manufacturing, immense fixed costs (such as expensive factories, heavy machinery, and specialized labor) mean that a single plant must churn out hundreds of thousands of cars annually to make them affordable. Yet, the entire Philippine market at the time demanded only 30,000 to 50,000 cars a year. The government forcibly sliced this tiny pie among five companies. With each plant producing a mere 6,000 to 10,000 units, the fixed costs per vehicle skyrocketed.

This lack of scale triggered a domino effect. Because the auto plants lacked volume, their local parts suppliers did too. Producing tiny batches of tires or glass drove local costs up to three times higher than mass-produced Japanese imports. To keep these inefficient local companies afloat, the government shielded them with tariffs and import restrictions. Filipino consumers were ultimately left holding the bag, trapped in a “captive market” and forced to pay a “protection tax” for overpriced, technologically outdated cars.

These state interventions merely cultivated “hothouse flowers”—businesses that look vibrant in a highly controlled, artificial environment but wither the moment they are exposed to the real world. Lacking genuine competitiveness, the PCMP's “winners” possessed no real financial resilience. When the macroeconomic crisis of the mid-1980s hit and foreign exchange dried up, the industry imploded. By 1986, production had plummeted to just 5,000 units, and four of the five state-sponsored automakers permanently shut down. As it turns out, the state can decree a policy, but it cannot decree a market.

What does this teach us? A lot, but primarily that a healthy dose of skepticism is required when discussing top-down government efforts. With current corruption scandals in the DPWH alleging budget leaks of up to 75 percent (with some critics even claiming 100 percent due to “ghost projects”), the burden of proof lies squarely on the government and crusaders of targeted industrial policy. This brings us to the core intellectual danger of the current industrial policy fad: the assumption that “state capacity”—the ability of a government to efficiently implement complex plans without dysfunctional corruption or inefficiency—is a tool we already possess, simply waiting to be wielded.

Economists Vincent Geloso and Alexander Salter, in their recent paper State Capacity and Economic Development: Causal Mechanism or Correlative Filter, argue that high state capacity is often an output of economic development, not necessarily the input that creates it. According to Geloso and Salter, state capacity emerges either to (1) engage in predation (by extracting wealth) or (2) resist predation (by protecting the wealth that growth attracts). In developing nations with weak institutions, attempting to build a massive, 'mission-oriented' entrepreneurial state through targeted industrial policy before the economy has matured often triggers the first outcome. When a state with low accountability grants itself the power to “pick winners,” it inadvertently hangs a “For Sale” sign on its policy-making machinery.

At its core lies the assumption that an inefficient, incompetent, and corruption-prone state can successfully “pick winners”, which is a code word for a new form of cronyism.

It is a train wreck in the making.

___________________________________________________________________

Jam Magdaleno is head of Information and Communications at the Foundation for Economic Freedom (FEF) and an Asia freedom fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and King’s College London.

Cesar Ilao III is a researcher and communications specialist for the Foundation for Economic Freedom (FEF). He is a lecturer at the University of the Philippines and was formerly a researcher at Monash University, Australia.