National policy on healthcare is ultimately a statement of values: what a country chooses to protect, whom it chooses to serve, and how seriously it takes the well-being of its people. President Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr.’s emphasis on health spending in the 2026 national budget sends a clear signal that healthcare is not merely a social service but a pillar of national development and human security.

The ₱427 billion appropriation for the Department of Health and PhilHealth, complemented by more than ₱13 billion for specialty hospitals and over ₱1 billion for medical scholarships and tuition fee subsidies in state universities and colleges, reflects a renewed attempt to strengthen the country’s health system from financing to service delivery. These investments matter. But their ultimate success will depend not only on infrastructure and funding, but on the availability, competence, and equitable distribution of health professionals across the archipelago.

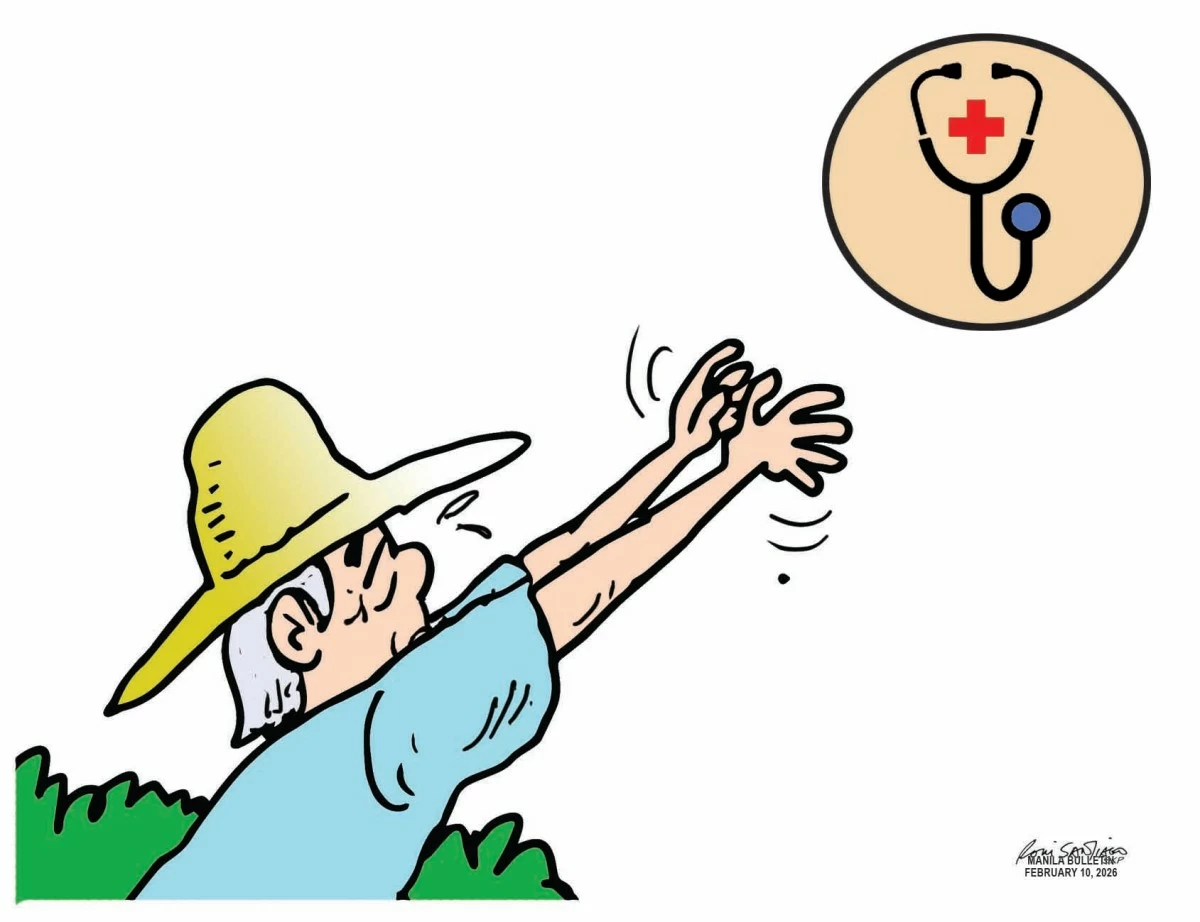

For decades, the Philippines has faced a paradox. We are a global supplier of nurses, caregivers, and medical professionals, yet many Filipinos—especially those in geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas (GIDAs)—continue to struggle to access basic health services. Rural health units remain understaffed. Doctor-to-patient and nurse-to-patient ratios in far-flung provinces lag far behind national and international benchmarks. The result is a health system that works reasonably well in urban centers but falters in the rural areas where the need is often greatest.

An ample supply of health professionals in all corners of the country is not a luxury; it is a necessity. Preventive care, maternal and child health, disease surveillance, emergency response, and the management of chronic illnesses all depend on trained personnel who are physically present in communities. No amount of hospital construction or insurance coverage can substitute for a doctor, nurse, or midwife who can examine a patient, make timely decisions, and provide reassurance in moments of vulnerability.

This is where investments in medical scholarships and tuition subsidies assume strategic importance. By lowering financial barriers to medical and allied health education—especially in state universities—the government can widen the pool of future health workers. But scholarship programs must be deliberately designed to serve national needs. Incentives, return-service agreements, and career pathways that encourage graduates to practice in underserved areas are essential. Training more professionals without addressing deployment risks perpetuating the same geographic inequities.

Equally crucial is retention. Health workers assigned to GIDAs face professional isolation, limited facilities, personal hardship, and security concerns. Competitive compensation, decent housing, continuing education, telemedicine support, and clear paths for career advancement can make service in these areas not merely an obligation, but a viable and honorable choice.

A strong health workforce also strengthens national resilience. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how quickly health emergencies can overwhelm systems that lack depth and reach. Future crises—whether pandemics, climate-related disasters, or demographic pressures from an aging population—will test the system again. Preparedness begins with people.

Health policy, therefore, must be pursued as a priority in long-term nation-building. Budgets must be matched by governance reforms, accountability, and coordination between national agencies, local governments, and educational institutions. Universal healthcare cannot be achieved through financing alone; it must be built on human capacity that reaches every barangay.

In the end, the measure of a healthcare system is not how much is spent, but who is served. Ensuring that every Filipino—regardless of geography—has access to a competent health professional is both a moral imperative and a sound investment in the country’s future.