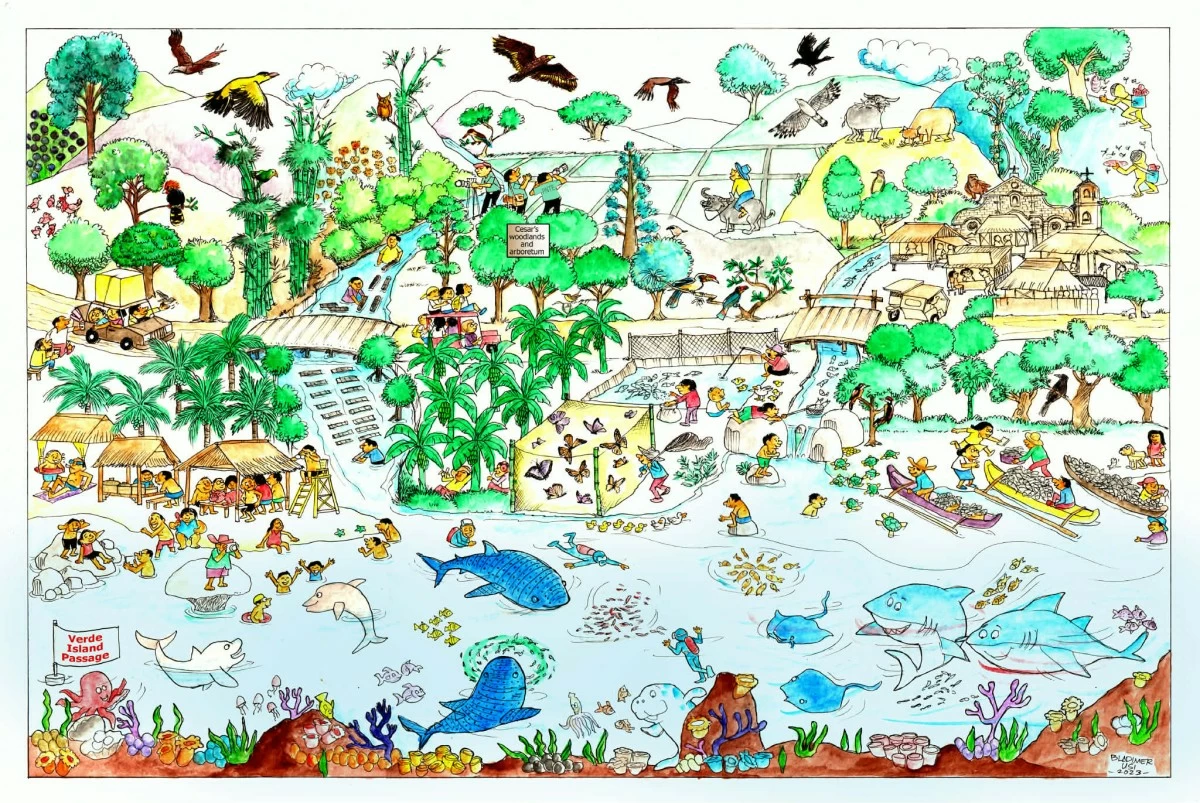

Various forms of life thrive at the Verde Island Passage. (Photo by Boogs Rosales)

The Philippines is home to a wealth of marine habitats, yet images of poverty and environmental degradation continue to define many of its coastal communities.

Spanning more than 1.4 million hectares, the Verde Island Passage (VIP) lies in the western Pacific Ocean and covers parts of Batangas, Marinduque, both sides of Mindoro and Romblon. Despite its global recognition as a marine biodiversity hotspot, communities along and beyond its coastlines are experiencing what appears to be a gradual decline in quality of life. Oil spills, loss of livelihoods and widespread corruption that weaken natural defenses remain persistent problems.

Scientists and experts have offered insights and possible solutions to address what has become a growing crisis. The message is consistent: listen to science and listen to the Indigenous Peoples (IPs).

A scarcity of scientists

“There are not enough scientists.” said Dr. Terrence Gosliner, a researcher from the California Academy of Sciences (CAS).

Gosliner and his team continue to document previously unknown species in Verde Island Passage, often discovering them faster than they can be formally identified.

“The Verde Island Passage is the richest place in the marine realm. Everywhere you look, there's astounding diversity,” he said.

While scientists are trained and knowledge is shared more widely, Gosliner noted that the pace of discovery still outstrips available resources.

“We can't keep up. The discovery is too big. We need more people to be involved in this,” he added.

He also noted that the VIP has long been affected by international shipping and industrial development, pushing it closer to the brink of biodiversity loss.

“Our understanding of the Verde Island Passage has largely come from a scientific perspective, but we also need to consider historical relevance, community interaction, shipping activity, industrial development and fisherfolk livelihoods. Conservation strategies must embrace all these elements,” he said.

Protecting a fragile paradise

One common and damaging misconception, scientists said, is the belief that corals are merely rocks. Educating the public that corals are living animals is a crucial step toward protecting the Verde Island Passage, according to California Academy of Sciences (CAS) scientist Dr. Meg Burk.

Coral reefs face multiple threats, including pollution, climate change, unregulated industrial activities and unsustainable fishing practices. When corals bleach, their ability to obtain food decreases, making them more vulnerable to disease and predation.

“With warming oceans, you get coral bleaching. ‘Bleaching’ refers to corals turning white. It looks like someone poured bleach on them,” Burke explained.

She said that if bleaching is not too severe or frequent, the corals can still recover, regain their algae and survive.

“So many people around the world depend on coral reefs for food, ecotourism and storm protection. There is still hope. Once people understand that corals are living organisms, it becomes easier to see why protecting them matters,” she added.

Learning from indigenous knowledge

When biodiversity is at risk, experts stress the importance of consulting Indigenous communities. Archaeologist Dr. Ame Garong of the National Museum of the Philippines said indigenous knowledge must be integrated into present-day environmental analysis.

“Whatever we do, we have to ask them,” Garong said. “In Mindoro, before entering any site, we consult with Indigenous Peoples because they have their own understanding of sacred places that cannot simply be accessed.”

Across generations, Indigenous communities have consistently shared one principle: do not harm the land, flora or fauna. Yet these boundaries are often violated by unchecked exploitation.

Artwork on sustainability and Barako 77.

Remembering the VIP’s history

Long before the Verde Island Passage gained global attention, it faced an enormous environmental threat from a proposed copper smelter and fertilizer complex that could’ve caused widespread ecological damage. The project was halted after residents of San Juan, Batangas, known as San Juaneños, mounted a peaceful but firm community-led protest.

That resistance, together with the work of Barako Publishing, which released the book "Barako 77: The Story of Environmental Activism in San Juan, Batangas," later led to a municipal ordinance declaring Oct. 22 as Araw ng Pagkakaisa para sa Kalikasan ng Bayan ng San Juan (Day of Unity for Nature in San Juan).

During a recent commemoration held alongside the Asia-Pacific Regional Scout Jamboree in Botolan, Zambales, about 23,000 international scouts learned about this history, as well as the importance of environmental advocacy, biodiversity protection, water conservation and plastic waste reduction.

Barako scouts

Meanwhile, 200 scouts and scouters from the Department of Education’s San Juan East and West districts and Batangas Eastern Colleges gathered locally to reflect on the past and take action.

Publisher and camp organizer Ciara Marasigan Serumgard said these efforts help young people “develop a unique identity, foster a sense of belonging and understand the movement’s values and purpose.”

The activities were aligned with the World Wide Fund for Nature Philippines’ “One Planet Lifestyle” initiative and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, helping nurture a new generation of environmental advocates.

Barako Publishing executive director Farrah Rodriguez said that since the book’s launch and the passage of the municipal ordinance in 2024, their alliance has played a crucial role in shaping the camp.

“Making memories like Barako Camp, in nature, and in one’s hometown, deepens our relationship with San Juan and helps make us genuine caretakers of it,” she said.

In an era marked by corruption and environmental neglect, it is easy to overlook those who bear the heaviest consequences—local communities and biodiversity. Accountability for environmental abuses remains essential. Progress will come not from industry-driven growth alone, but from governance rooted in responsibility, science and indigenous knowledge. Only then does a measure of hope emerge.