President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s approval of the National Digital Connectivity Plan (NDCP) is a policy milestone and a long-overdue admission that the Philippines’ digital journey has been built on paradox.

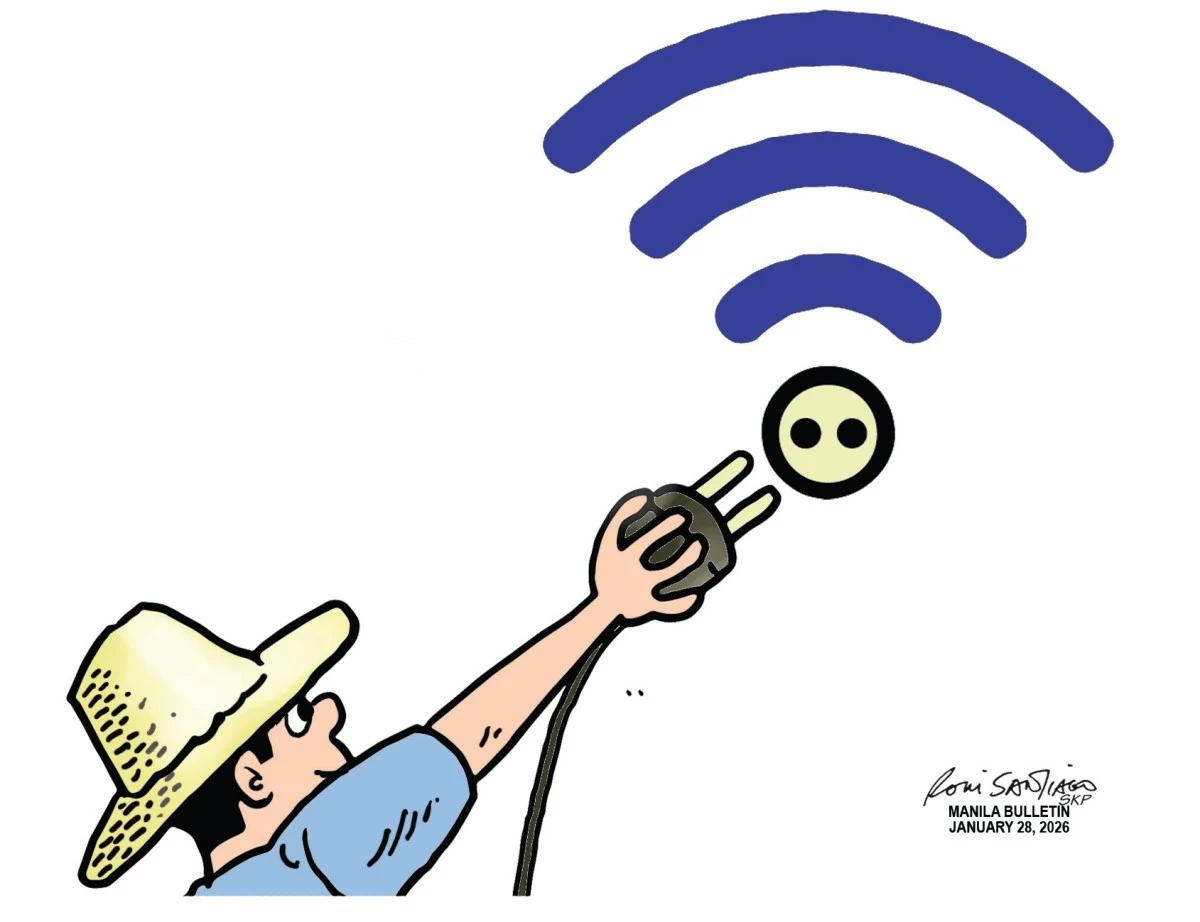

We are among the world’s most connected people socially, yet among the least connected infrastructurally. Filipinos spend some of the longest hours online globally, but millions still struggle with slow, expensive, or even nonexistent internet. The NDCP is a chance to resolve this contradiction—if we choose to use it boldly.

And the numbers are sobering reminders. The Philippines ranks near the bottom in 5G connectivity, and only about a third of households had fixed broadband as recently as 2023. And the gap could have even widened with population growth. This gap is both a technical failure and a social one. With almost every aspect of life going digital, poor connectivity limits access to education, health services, jobs, e-commerce, and civic participation. In a country where geography already divides opportunity, weak digital infrastructure deepens inequality, leaving rural and low-income communities further behind.

The NDCP, as a long-term master plan, must therefore be treated as a national mission, not just a policy in its bucket list. Government must ensure that broadband rollout prioritizes inclusion, not just profitability. This means pushing infrastructure into “unviable” areas—far-flung islands, mountainous provinces, and underserved urban communities—where the market alone will not go. Streamlining permits, enforcing infrastructure sharing, and aligning national and local governments are crucial if we have to attain this objective. So is transparency. Progress targets must be public, measurable, and regularly reported, so the plan does not fade into another well-written but poorly executed strategy.

But the government cannot, and should not be left to do this alone. The private sector plays big and crucial roles in the country’s connectivity challenge. Telecommunications companies, tower firms, satellite providers, and tech platforms have the capital, expertise, and innovation capacity to accelerate progress. Their role, however, must go beyond maximizing returns in already lucrative markets. If the private sector wants to be a true partner in nation building, it must strike a better balance between profit and service.

This does not mean abandoning profitability, which is crucial in sustaining business. It means embracing smarter models: infrastructure sharing instead of duplication, tiered pricing that makes basic connectivity affordable, and long-term investments that value social impact alongside financial returns. Public-private partnerships under the NDCP should reward companies that expand access, improve quality, and lower costs—not just those that move fastest where profits are guaranteed. Nowadays, connectivity is no longer a luxury product; it is a public utility in all but name.

Schools, cooperatives, and local communities can pool resources, promote digital literacy, and ensure that access translates into meaningful use—not just scrolling, but learning, creating, and participating.

Yet closing the digital divide is not only a government or corporate responsibility. Each Filipino has a role to play. Citizens must demand better service, support policies that promote competition and accountability, and resist dismissing poor connectivity as a norm.

The NDCP gives the Philippines a rare opportunity to align its digital habits with digital infrastructure. We, as individuals, are already connected in spirit. The challenge now is to become a connected nation in reality. Whether this plan becomes a turning point or another missed opportunity will depend on our collective will—of the government to lead decisively, of the private sector to serve responsibly, and of Filipinos to insist that in a digital age, no one should be left offline.