The Manila of my Lola, 1905-1955

What was life like in old Manila?

At A Glance

- The map allowed me to visualize my own family history.

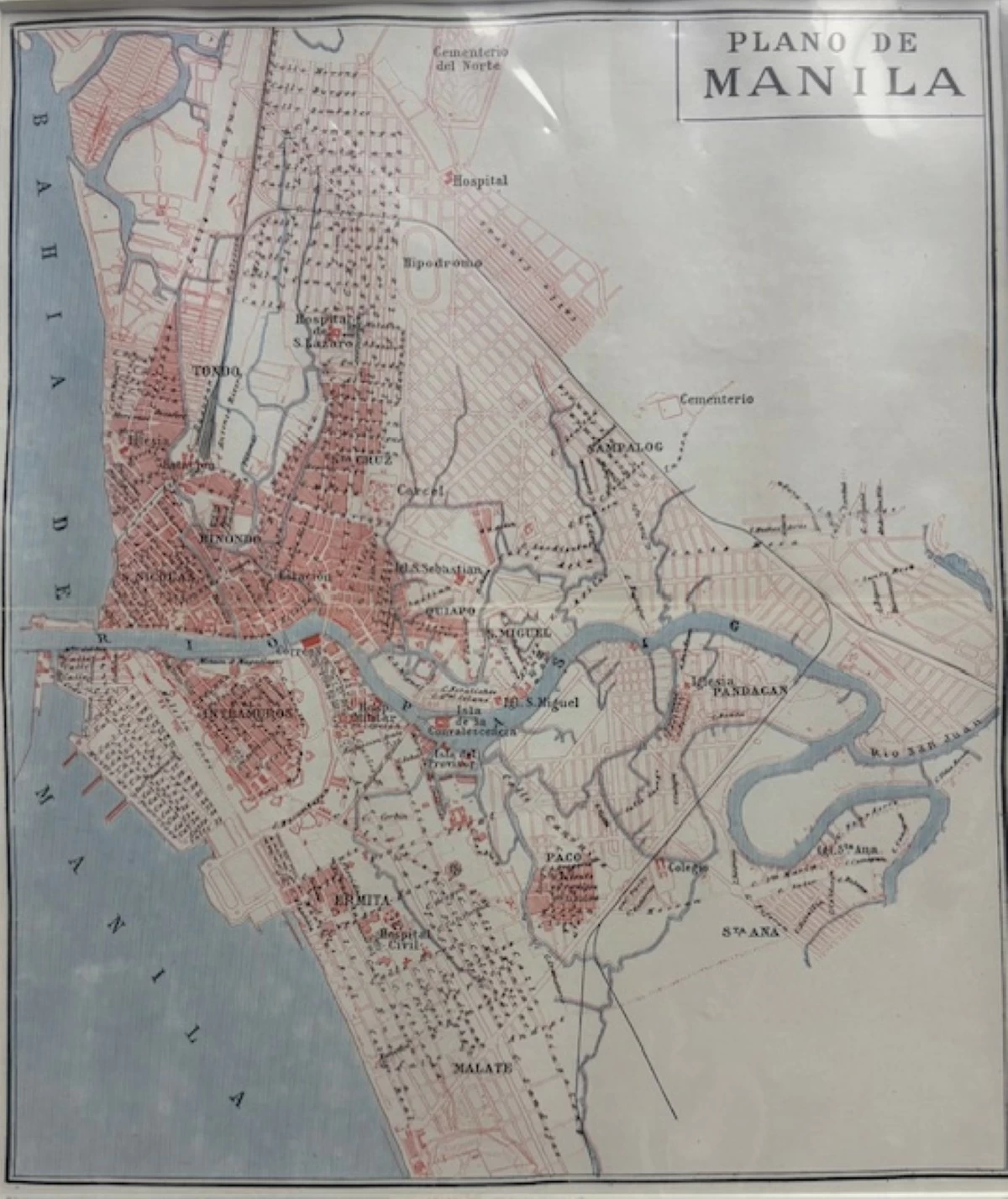

'PLANO DE MANILA' This map shows the layout of Manila in 1905.

I came across a map, “Plano de Manila,” showing how the city was 120 years ago, in or about 1905. That was shortly after we transitioned from being a Spanish colony to being an American colony. Streets were still called “calle,” but Taft Avenue and Avenida Rizal were already in existence, and streets were already named Pennsylvania, Colorado, Florida, and other US states that sent volunteers to fight in the Filipino-American War.

Land had been reclaimed south of the Pasig River to create the Port Area and the future sites of Manila Hotel, Wallace Field, and the Army and Navy Club. The Tondo shoreline, however, was still just meters away from Plaza Moriones fronting Tondo Church, and grand mansions on the west side of Calle Real (now M.H. del Pilar) backed directly on the beach.

Intramuros had, of course, long been settled, as was the area north of the Pasig embraced by Azcarraga. San Lazaro Hospital had moved in the late 1700s from near Intramuros to its present location, then distant countryside. By the time of “Plano de Manila,” the area along Avenida Rizal up to San Lazaro was already urbanized. Ermita and Malate were still nipa hut territory, and the present districts of San Miguel, Sampaloc, Santa Mesa, Pandacan, Paco, and Santa Ana were villages surrounded by rice fields and bamboo groves.

Among the landmarks on the map are “carcel” (Bilibid Prison), “cementerio del norte” and a nearby hospital that was probably the Chinese General Hospital, “hipodromo” (the San Lazaro Race Track), another “cementerio” beyond Sampaloc (the one at Balic Balic), “hospital civil” (now the Philippine General Hospital) in Ermita, and “colegio” that must be Colegio de la Concordia. Tutuban Railroad Terminal and the railroad tracks leading north and south are traced.

The map also shows esteros leading north through the still rural area between Carcel and Sampaloc, and also south of the Pasig. There are few traces of them now, explaining why España near the University of Santo Tomas (UST) and Taft Avenue near Rizal Park are flooded with every downpour,

Today’s Quezon City is all blank, being agricultural land of the Tuason mayorazgo granted by the Spanish government to reward the family patriarch Son Tua for loyalty during the British Occupation (1762-1764).

Part of Sampaloc belonged to the Real Monasterio de Santa Clara. The monjas appear to have decided to cash in on their property, and several blocks of Calles Honradez, Sobriedad, Lealtad, Economia, Constancia, and Trabajo are already on the map. The vittues, by the way, happen to be near Calle Gardenia, a rather busy red light district. Dotted lines mark the virtues’ continuation towards San Lazaro. There is, however, no indication yet of the later major arteries Quezon Boulevard, España, and Dimasalang, nor of a site intended for the UST that moved from Intramuros two decades later.

The map allowed me to visualize my own family history.

My mother’s family is from Bulacan, but in the 1890s, my Lola Trining and her sister Lola Sanang, then orphaned teenagers, moved to live with relatives in Manila. I asked Lola Trining if she went to see Rizal’s execution, and she said, “No, I would have cried.” Lola Trining married and had two daughters, Nanay (nicknamed Binay) and Tia Juli. They lived on Calle Requesens near San Lazaro, called “Little Marilao,” where many townmates had settled. Later, they moved to Tondo, near Plaza Moriones, on Calle Anloague (now Juan Luna), where the large Iglesia ni Cristo church stands. Tia Juli related how they would dig for clams on the beach where Mary Johnston Hospital later stood.

Other relatives persuaded them to move to the new development in Santa Cruz near Hipodromo, and their two-story house rose in 1932 on 115 Karapatan Street, beside Tio Terio and Tia Hilda.

My mother went to Manila North High School on Calle Timbugan (later Teodora Alonso Street). One of her teachers was the then Miss Concepcion Hidalgo, who lived on Calle Magdalena, a short distance away. Nanay told me that one day, she invited the class to her home to show them her wedding dress. She was about to marry Claudio Sandoval of Palawan. In the fullness of time, I married the youngest Hidalgo-Sandoval daughter.

My father was born in San Manuel, Pangasinan, and went to school at the town’s public elementary school. There was only one public high school per province then, and at age 13 or so, he moved to Lingayen to attend Pangasinan Provincial High School and eventually to Manila to enroll at the University of the Philippines, where he met Nanay. Both graduated BSE in 1932. He taught English at Manila East High School (now Mapa High School) and lived, I believe, on Calle San Anton in Sampaloc until he and Nanay got married.

I was born in 1939 and lived on Karapatan Street until age 16. I went to Dr. Alejandro Albert Elementary School on Dapitan, and from 1945 to 1949, walked to school via the already completed Constancia and Economia Streets or along the railroad tracks.

So much has changed since the flood- and traffic-light city of “Plano de Manila.” Since 1928, when Nanay saw my future mother-in-law’s wedding dress, since 1932, when the house on 115 Karapatan was built, since 1955, when we moved away to a blank spot on the Plano that is now near the Skyway exit to traffic-heavy Quezon Avenue.

I hope Metro Manila planners are looking beyond flood control and Manila Bay reclamation in planning Manila of later in this new century.

Notes: (a) The map is from Encyclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana, published by Espasa Calpe, S.A. (Bilbao, Madrid & Barcelona, 1926). It was offered by Rudolf Lietz’s Gallery of Prints, and (b) Most of the Chinese community sided with the Brits in the British Occupation of Manila, except for the wealthy Son Tua, who was with the Spanish. After the war ended, the Brits left, and Son Tua was rewarded with a mayorazgo for this loyalty; and (c) a mayorazgo is a legal mechanism that allows entailed property to descend to the eldest male heir, thereby preserving the family’s wealth over generations. Son Tua was granted a mayorazgo on land comprising much of the present Quezon City and Marikina. The mayorazgo existed until the American colonial period, when the Supreme Court dissolved it after family litigation.

Comments are cordially invited, addressed to [email protected]