Architecture directly translates and reflects society's ever-evolving needs, culture, and environment. Yet, we often build static buildings that cannot adapt to our changing nature. This is especially true for Filipinos due to our rapid urbanization, vulnerability to natural disasters, and dynamic lifestyle due to our modern concept of family. We have OFWs who come and go regularly, multi-generational households, and much more. Do our buildings adapt to our ever-changing needs, or do we adapt to our buildings?

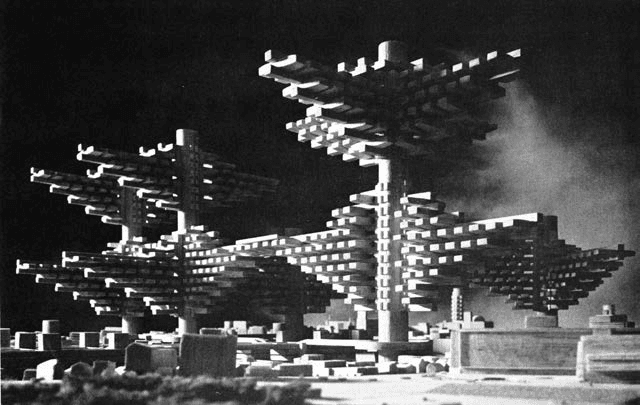

In the mid-20th century, Architects Kenzo Tange and Kisho Kurokawa introduced a revolutionary architectural philosophy called Metabolism. It emphasized flexible, expandable, and sustainable designs that could "grow" and adapt like living organisms. Buildings and cities were imagined as organic systems capable of regeneration, much like living beings. At the forefront of this philosophy was the technology that allowed us to construct prefab and modularly. It focuses on the efficient use of space as it caters to the specific needs of the people. I believe that the Philippines does not have a lack of space; we have an inefficient use of space issue.

One immediate application of metabolism architecture in the Philippines could be in urban housing solutions. As Metro Manila and other urban centers continue to grow, space becomes increasingly limited. A metabolism-inspired approach would advocate for modular housing units that are pre-fabricated and can be easily expanded or reconfigured as family needs change.

The 2016 Pritzker Architecture Prize laureate, Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena's work on public housing is a peek of what metabolism architecture can do for housing. He noticed that most public housing projects fail because the designers don’t understand the exact needs of their future inhabitants. Therefore, his design focuses on providing all the necessities in a portion of the house while leaving gaps between houses wherein families can build additions as their resources grow. He coined the concept "participatory design process." It plays well with the metabolism philosophy because it allows the homeowners to adapt their space to their exact requirements.

Aside from flexibility and adaptability, the metabolism philosophy applied to housing can help the Philippines be more resilient in the face of natural disasters. By adopting modular adaptable building systems, Philippine architects could create structures that are easier to repair, expand, or reconfigure after natural disasters. For example, homes could be designed with replaceable modules that can easily be swapped out if damaged, minimizing the cost of time needed for rebuilding. This can also be applied to highly crucial buildings such as hospitals and schools.

Looking back at our pre-colonial history, the Philippines actually had this concept of metabolism with our "Bahay Kubo," wherein we expand the house based on needs. Due to its lightweight and modular nature, we even had the concept of "Bayanihan," wherein the whole community would get together to move the houses when the need arose. We used to adapt our housing to our changing needs and not the other way around. Metabolism architecture is in our roots.

By embracing flexibility, modularity, and community-centered design, architects can create structures and cities that evolve with time, needs, and environmental conditions. Just as Metabolist thinkers imagined a city of the future shaped by organic growth and technological progress, the Philippines can craft its own version—one rooted in tradition yet boldly moving toward a sustainable future. By examining the core concepts of metabolism and exploring its applications to our Filipino setting, Philippine architecture can then be more resilient, sustainable, and equitable.