The International Criminal Court (ICC) was established in July 2002 in Rome, Italy, in a bid to hold individuals accountable for the most heinous crimes under international law, including genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. However, for the ICC to effectively carry out its mandate, the cooperation of state parties is paramount. Without their cooperation, the ICC risks being reduced to a powerless, toothless body, unable to perform its mandate.

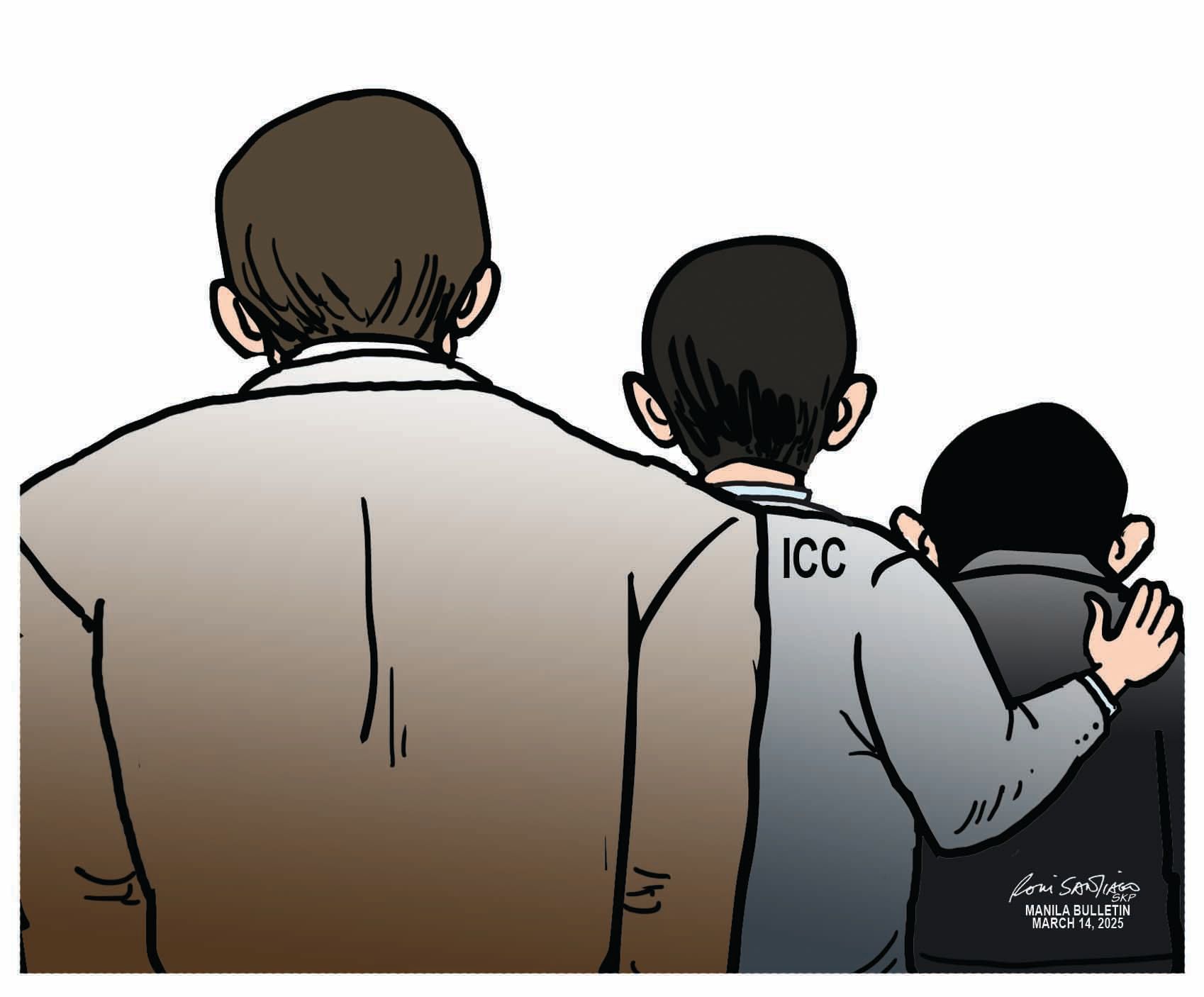

The arrest of former president Rodrigo Duterte on March 11, 2025, underscores the crucial role state parties play in the success — or failure — of the ICC. Duterte’s arrest, which was ordered by the ICC in response to his bloody war on drugs, is a prime example of how state parties can, at best, indirectly support the ICC’s efforts — or, at worst, undermine them.

While the Philippines refused to cooperate with the ICC after officially withdrawing from the Rome Statute in 2019 under Duterte’s administration, the court’s investigation into his bloody war on drugs — which started in 2017 — continued.

But Duterte’s arrest became a symbol of both the ICC’s authority and the challenges it faces without state support. His arrest would not have been possible without state cooperation — in this case the Philippine government indirectly cooperating with the ICC through the Interpol.

What makes this situation even more significant is the broader context of state party compliance with ICC mandates. The Philippines' refusal to cooperate with the ICC is not an isolated case. Other high-profile cases, such as the arrest warrants for Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir and Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, highlight the difficulties the ICC faces in holding perpetrators accountable when state parties are unwilling to assist in enforcement. Al-Bashir, for example, was indicted by the ICC in 2009 for crimes related to the Darfur conflict, yet numerous African Union states, despite being ICC members, refused to arrest him, citing concerns over sovereignty and political considerations. Gaddafi, too, was the subject of an ICC arrest warrant, but he was never captured, largely for lack of enforcement cooperation from the Libyan state and other countries at the time.

These instances demonstrate the grave limitation of the ICC's ability to function effectively in the absence of state party cooperation. The court lacks the policing powers or enforcement capabilities to act unilaterally. It relies heavily on the commitment of state parties to apprehend suspects, extradite them, and execute its orders. If these states fail to do so, the ICC is rendered ineffective, as demonstrated by its repeated inability to arrest high-profile personalities despite its legal orders.

The situation with Duterte, despite a notable moment of indirect cooperation, calls for a deeper reflection on the role of state parties. It underscores the need for greater commitment and cohesion in upholding international justice. The future success of the ICC depends on both the legal and moral obligation of states to follow through on arrest warrants, even when it involves political or diplomatic complexities. If states are allowed to cherry-pick when they will cooperate, the ICC risks becoming a symbolic institution, unable to fulfill its mission of delivering justice and holding perpetrators of the world’s worst crimes accountable.

To ensure the continued relevance and success of the ICC, it is crucial that state parties are committed to cooperating with the international court, not just in principle, but in practice. Anything less will render the ICC a toothless entity, and the dream of international justice will remain just that—a dream.