Picture perfect

Portraits were taken more seriously in olden times.

WALA LANG

A minute to fix hair, test dimples, tuck tummy in before extending arm. Click and—voila!—a portrait. The background could be Boracay’s white sand, Luna’s Spoliarium, a lechon, Eiffel Tower, a fiesta procession, whatever, wherever. Once approved, the selfie remains in the iPhone, mostly unseen and forgotten until it gets erased by mistake or weeded out when the latest model hits the market.

Portraits were taken more seriously in olden times. People dressed up and had themselves shot by someone like Chat Peypoch, posed before floodlights, reflectors—all the bells and whistles. Rows of large portrait photos hung in many an ancestral house, mounted behind glass in narra frames carved maybe by Tampingco, with anahaw leaves and ylang-ylang flowers.

My mother had an album with postcard size formal sweet 16 portraits of her and her girl classmates, taken in 1928 when they were graduating from Manila North High School. It and other albums would be proudly brought out for visitors to admire.

Wealthy families had family portraits in oil on canvas. A Paterno family home had a long hall lined with oil portraits of three or four generations by artists from the early 19th century, from Severino Flavier Pablo to Araceli Dans. One family member was portrayed by Justiniano Asuncion as a beautiful young lady and again as an elegant older woman by Fernando Amorsolo. Juan Luna is said to have dashed off several siblings’ portraits in one afternoon, before leaving for study in Spain. Simon Flores de la Rosa painted portraits of Palawan’s Sandoval family brought a Manila painter to Coron to immortalize them on canvas. A family member recalls there were more than a dozen portraits in all. Sadly, the family home was bombed in 1945 and only four survive.

In Malacañang are portraits of past Presidents and First Ladies among others by Fernando Amorsolo and Lulu Coching Rodriguez. The National Museum and other public and private collections proudly show portraits by National Artists Amorsolo, Victorio Edades, and Vicente Manansala and outstanding artists such as Romulo Galicano, Gig de Pio, Onib Olmedo, Romulo Galicano, and Betsy Westendorp. Manansala had a long waiting list and some ladies wanted the artist’s works so strongly that they agreed to be painted in the nude. They undressed but posed with face averted so I suppose they don’t count as portraits.

A cousin and I once traced our family tree (Roxas and del Carmen from Marilao, Bulacan), which made me wonder what my ancestors looked like. I was able to find good photos only of two grandparents and a fuzzy snapshot of one. Enlarged, they now keep watch in a corridor at home.

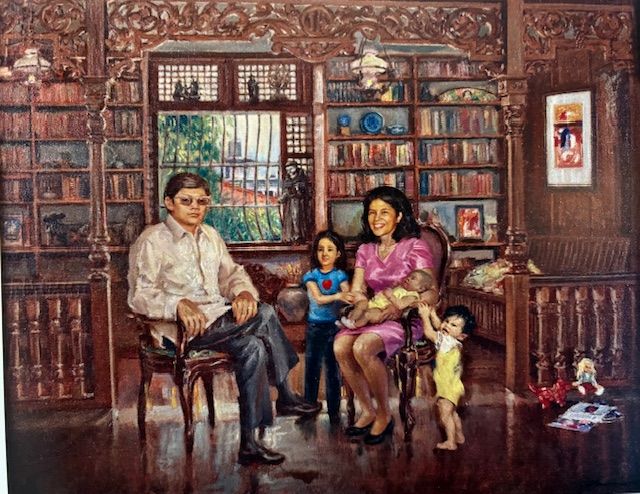

I decided to continue with a portrait of wife Alice, daughter Mianne, and me in our sala, in what art historians call a “conversation piece.” These are works showing people doing something or in an informal setting. I was a University of the Philippines assistant professor then and persuaded a fine arts colleague, Carlos P. Valino Jr., to do the job.

Charlie and I were both busy so he came to the house only on Sunday mornings. It took a record five years to finish the job. Charlie would arrive about 9:30 but we were both talkative and had lots to talk about—goings on at U.P., his and my little triumphs and frustrations, world peace, and all that. I learned a lot about painting, too—about colors, perspective, and techniques like using a carpenter’s pitik to establish the painting’s three or four vanishing points.

He was an excellent painter, observing that it wasn’t easy to allow for four sources of light (two lamps, open window at the back, and glass doors behind him); that there were hundreds of books of different colors and sizes on floor-to-ceiling shelves; that the arch was not only heavily carved but also see-through; the shine on the floor, etc. A Joya collage was on a wall. He did it with a few strokes, muttering something like, “And they say abstracts are hard to do.”

He got my face in one go but had to erase and redo Alice’s three or four times. He proudly pointed out, however, that not everyone can paint a recognizable face that was as large as a 10-centavo coin.

The carved arch, incidentally, was a junk shop find, salvaged from some old house. One side had the carved initial “FM” and I thought it would have been nice were its match on the back side, “IM.” How could I have guessed that “LM” would be just right 50 years later.

Anyway, before we knew it, it was time for lunch and Charlie had to pack up and go. All in all, he must have put brush to canvas for like 30 minutes each visit.

He began when we only had our eldest, Mianne, who was about seven (she refused to stand still unless in shirt and jeans). After a year or so, our son Jem was born and was already running around but objected to being painted, which is why he was added, bawling. (Note: no sign of him when Charlie began.). Then Sandra arrived so Charlie painted her on top of the handbag that was originally on Alice’s lap.

Every so often, Charlie would notice that the trees in the backyard had grown so he would add a few strokes to the painted greenery.

Time passed and another stork was spotted. That did it. Charlie had to finish quickly or it would look like we had twins. He dashed off the doll on the floor and we later explained to Amy that the doll was she.

The family portrait gallery has grown and now has pieces by Gig de Pio, Angelito Antonio (Lito tells me it’s the only portrait he has painted), Elmer Borloñgan, Alfredo Roces, Federico Aguilar Alcuaz, Napoleon Abueva (a bust), and letras y figuras of five grandchildren by Alvaro Jimenez. All of us do selfies, too.

Comments are cordially invited, addressed to [email protected].