Where the Defender ends and the Octa begins

Behind the wheel of the Land Rover Defender Octa

At A Glance

- A two-event test program revealed how differently the Defender and Defender Octa behave when pushed to their limits.

- The regular Defender prioritizes grip, stability and controlled progress, while the Octa unlocks speed, rotation, and performance rarely seen in an off-roader.

- Advanced systems like 6D Kinetic suspension and Octa Mode allow the Octa to perform with the attitude of a fast road car on loose surfaces.

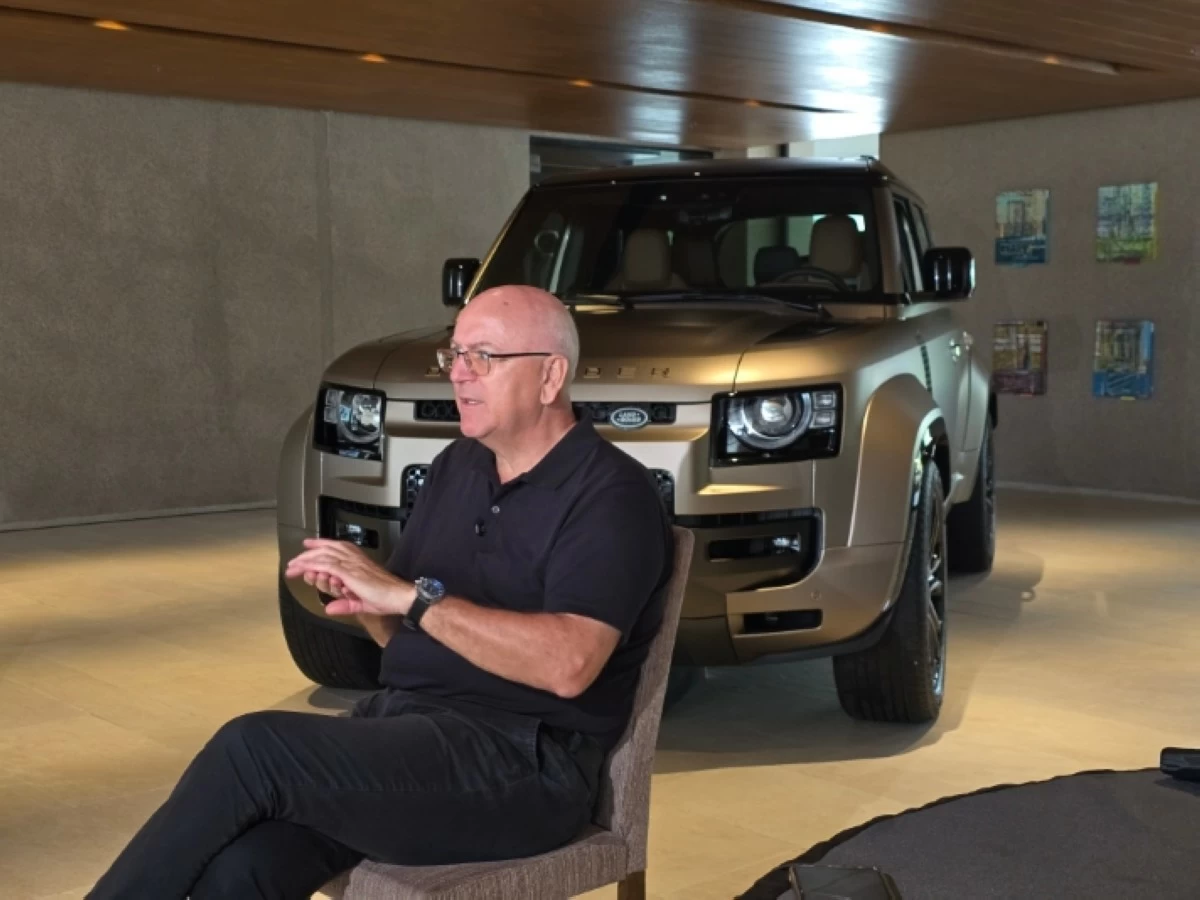

The Land Rover Defender has long stood as one of the most respected off road nameplates in the world, a vehicle built on the expectation that it will go farther and endure more than anything else in its class. My recent experiences with the Defender and the Defender Octa showed just how wide that spectrum has become. In two events held only weeks apart, I saw the regular Defender operate at its natural limits and then watched the Octa break through boundaries the nameplate has never approached before.

Into the jungle

The first event was built around the regular Defender’s off-road capability, with the Octa serving as our road companion from the city to the foothills of Rizal. Riding in the Octa on the way to Tanay immediately hinted at what separated it from the rest of the lineup. With Dynamic mode engaged, its 4.4-liter twin-turbo V8 delivered the kind of surge associated with a fast road car. The Philippine specification lists the engine at 635-PS and 750-Nm, backed by a widened track, extended suspension travel and a reinforced body structure. The Octa felt planted and aggressively responsive, its steering settling into a precision uncommon in this category. Even from the front passenger seat, the differences were obvious in the way I felt it through my bum.

As we got to Jungle Base in Tanay, the focus shifted back to the Defender I knew better. I drove the Defender 110 D250, powered by a 249-PS, 570-Nm diesel engine. Through steep muddy climbs, rutted paths, off-camber sections, and a quick rocky river run, the vehicle behaved exactly as expected. It corrected itself at every provocation, settled quickly in loose soil, and insisted on retaining grip even when I tried to coax slip out of it. That instinct is embedded in the Defender’s DNA, and Chris Ward explained it plainly: "The principle of a Land Rover is not to lose grip. So we’re trying to prevent understeer, we’re trying to prevent oversteer, we’re trying to make sure that you’ve got some traction."

One of the more revealing exercises that day was a blind trail crawl. Guided only by the external cameras and cut off from any forward visibility by a sunshade over the windshield, I had to work through an uneven riverbank without the comfort of a direct line of sight. Many off-road vehicles now offer 360-degree cameras, but this showed how much the Defender’s system can accomplish when the usual visual references disappear entirely.

The regular Defender’s role is to protect you from your own mistakes. It reads the terrain and ensures that progress continues as smoothly as possible. In the hands of an expert, I have no doubt that this vehicle is capable of so much more.

Speed, and more speed

The second event, held in Alviera, Pampanga, removed the restraints entirely and placed the Defender Octa at the center of the program. Here, the question was not how capable a Defender could be. It was how far Land Rover could push the platform if given the freedom to engineer for high-speed performance.

The prepared Octa Arena, a specially prepared course within Alviera, was a mix of flat tarmac and twisty hillside descents that opened up to an open field where the Defender Octa could really stretch its legs. Tearing through the tarmac in Dynamic mode, the 2.7-ton SUV changed direction with a sharpness that felt closer to a rally car than an off-roader. Its 6D Kinetic suspension worked constantly to manage body movement and keep all that weight under tight control. As the special Octa Mode was turned on, riding across the loose surface course revealed an experience that felt detached from what the nameplate traditionally stands for. Acceleration came instantly, and braking stayed consistent even as grip levels shifted from patch to patch. Full-throttle through the sand and gravel, catching the exit with opposite lock, and the body stayed remarkably composed throughout the run. None of this would be possible in a normal Defender, which simply is not programmed or engineered to behave this way.

The Octa abandons traditional anti-roll bars entirely, relying instead on its hydraulic architecture capable of reacting up to 400 times per second. Removing anti-roll bars creates more articulation off-road, while the hydraulics maintain a level body during aggressive cornering. Coupled with the wider track, revised suspension geometry, and a strengthened chassis, the Octa gains the ability to rotate, settle, and accelerate in ways the regular Defender never attempts.

Ward described Octa Mode, the system that unlocks this behavior, as the one point where Land Rover willingly steps outside its own doctrine. “The Octa mode is the only mode on the car that allows us to kind of compromise that mindset. So we can understeer, we can oversteer, we can four-wheel drift the car.” That description aligns exactly with what I felt at speed. The Octa acts with the urgency and confidence of a performance road car, but filtered through the mass, height, and all-terrain intent of a Defender. It is an unusual combination and one that defines the model’s identity.

One nameplate, two worlds

Experiencing both vehicles in two very different environments revealed their opposing personalities. The regular Defender is engineered to endure, survive, and move forward even when the terrain turns unpredictable. It is a stabilizing force. It corrects before you need it to. It is always looking for grip.

The Octa, however, is engineered for a different outcome. It uses its power, hydraulics, and widened stance to operate in the margins where a normal Defender refuses to go. It encourages rotation, allows controlled slip, and uses its hardware to behave like a fast road car on the right loose surface. It is an expansion, not a variation, of the Defender formula.

Both vehicles share the badge and the lineage. Yet after experiencing them back to back, it becomes clear that they now occupy two distinct worlds within the same family. The regular Defender carries its tradition forward. The Octa pushes that tradition into unfamiliar territory. And when given the space to prove it, the Octa shows that the Defender name can stretch farther than anyone expected.