Rice consumption outpaces production: Why Philippine farms struggle to keep up

Ateneo study shows Filipinos are eating more but producing less due to stagnant yields and farmland bottlenecks

At A Glance

- Ateneo researchers warn that the Philippines' rice output has been "largely stagnant" since 2017, contributing to an 18 percent consumption gap that forces the country to rely more heavily on imports

- In 2022 alone, Filipinos consumed 2.3 million metric tons more rice than the country produced

- While some regions have posted gains—most notably BARMM—many others continue to decline, widening the national shortfall

Ateneo researchers reveal that the Philippines’ rice production and farmland have stagnated over the past decade, deepening reliance on imports—even though urbanization is not entirely at fault. (Manila Bulletin / file)

Filipinos are consuming rice faster than the country can grow it, with a study from Ateneo de Manila University warning that stagnant farm yields and shrinking farmland are widening the nation’s rice deficit despite years of government interventions.

The Philippines consumed 2.3 million metric tons more rice than it produced in 2022, widening a supply gap that has left the country increasingly dependent on imports despite long-running government efforts to boost domestic harvests.

According to new research by Ateneo, the national rice deficit—now roughly 18 percent—has persisted due to stagnant farm productivity and the slow expansion of rice areas.

Henry A. Bartelet, Alenn Jhulia D. Prodigalidad, Janelle S. Dy, and Jan Gabriel N. Manzano published their paper, Understanding Rice Production Stagnation in the Philippines: Regional Evidence and Development Implications, in the open-access journal PLOS One.

Philippine rice output has ‘barely grown’ since 2017

A study by scholars from the John Gokongwei School of Management and the Department of Environmental Science found that rice production has remained largely flat for the past seven years, based on Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) data.

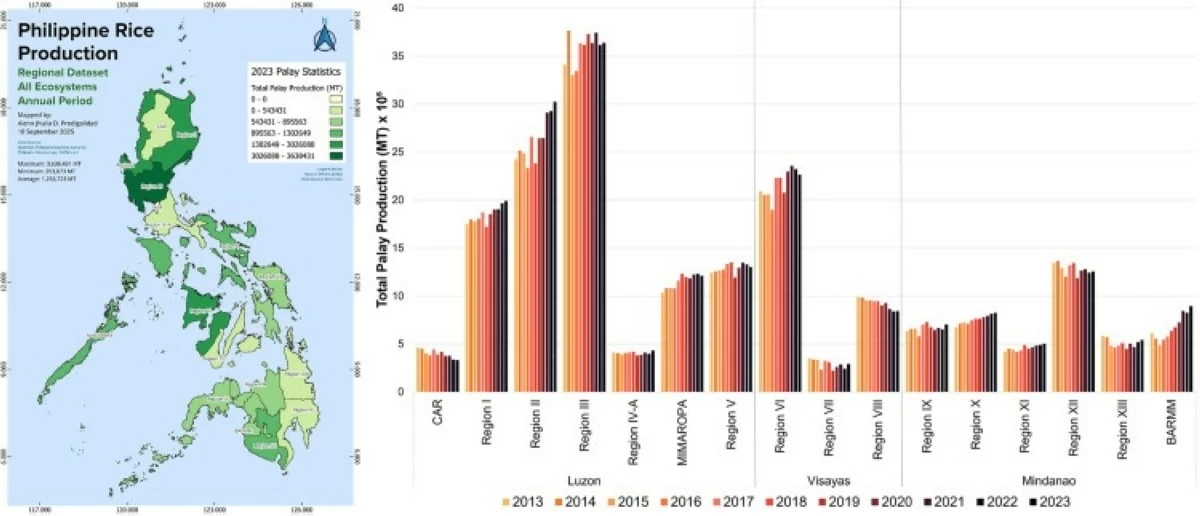

Regional differences in total production of unmilled rice in the Philippines from 2013 to 2023, based on PSA data. Source: Bartelet et al., 2025

From 2013 to 2023, the country’s total palay (unmilled rice) output rose only 9 percent, from 18.4 to 20.1 million metric tons. This growth lagged behind rising rice consumption and population increases.

Key indicators also showed minimal progress: rice farmland expanded by just one percent (4.7M to 4.8M hectares); average yields increased only seven percent, from 3.9 to 4.2 metric tons per hectare; and national output has been nearly flat since 2017, heightening the country’s reliance on imported rice.

Urbanization not the ‘main culprit’

Contrary to popular belief, the Ateneo researchers found little evidence that urbanization alone explains farmland stagnation. Instead, they attribute weak production growth to limited expansion of irrigated and cultivable farmland; persistently slow improvements in yield; climate shocks such as typhoons and droughts; and uneven public investment across rice-producing regions.

Sharp regional contrasts: Who’s growing and who’s falling behind?

The Ateneo study highlights stark regional differences in rice performance over the last five years.

Among the declining production regions from 2018–2023 are the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) with –15 percent and Eastern Visayas (Region VIII) with –11 percent.

The study pointed out that these areas experienced “rice farmland loss, stagnant yields, repeated typhoons and droughts, and competition as farmers divert land to other, more profitable crops.”

Meanwhile, the growth regions from 2018–2023 include the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) with +40 percent; Cagayan Valley (Region II) with +27 percent; and Ilocos (Region I) with +16 percent.

“These gains are linked to expanding irrigated areas, better yields, and support programs such as improved seed, farm mechanization, and targeted regional initiatives,” the researchers said.

In BARMM, increased political stability and dedicated rice infrastructure investments significantly boosted yields, the study added.

National programs not enough; regions need tailored support

While the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF)—established under the Rice Tariffication Law (RA 11203) and extended until 2031—has provided machinery, seeds, and training, the researchers say national-level interventions alone cannot address region-specific constraints.

The study recommends stronger, climate-resilient irrigation systems; region-specific support services and investment plans; better financing programs to reduce production costs; and focused infrastructure development in lagging areas.

The researchers also emphasized that closing the country’s growing rice deficit requires localized strategies, informed by both the successes of BARMM, Cagayan Valley, and Ilocos, as well as lessons from regions experiencing decline.