Who owns your data? Rethinking cybersecurity in the Filipino imagination

Image by Sanket Mishra from Pexels

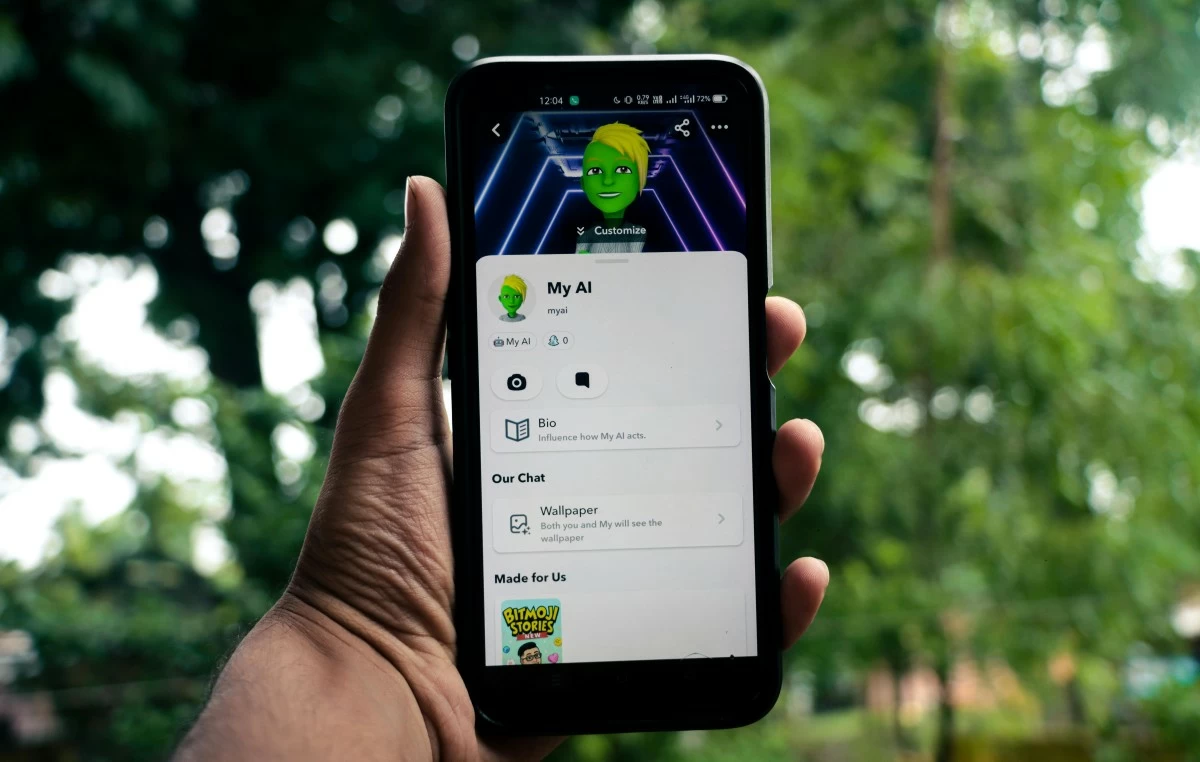

A few months ago, my feed was flooded with Ghibli-fied versions of my friends. One by one, they uploaded their faces through an AI photo app and re-emerged as soft-lit anime protagonists: riding bicycles, surrounded by flowers, sometimes with cats. It was charming, even nostalgic. But as I scrolled, a small question crept in: where do all these photos go?

For many Filipinos, cybersecurity is often reduced to one word: scam. It’s about avoiding suspicious links, ignoring texts from unknown numbers, or double-checking Facebook friend requests from accounts with blurry profile pictures. Warnings circulate like folk wisdom: “‘Wag click nang click.” And with good reason. Stories of people losing savings to phishing, fake job offers, or misdirected GCash transfers surface regularly.

But what’s striking is how narrow this understanding of cybersecurity is. Beyond scams, everyday digital practices are often treated as harmless, even playful. We upload selfies to apps without reading the fine print. We give away our full names, birthdays, and addresses to join online raffles. We answer surveys shared by friends, not realizing they can be fronts for data collection.

These aren’t isolated behaviors; they reflect deeper patterns. Filipinos are famously sociable online. We love to share, participate, and join in. Whether it’s a raffle from a local sari-sari store or a global platform promising “freebies,” these activities tap into a culture of trust and pakikipagkapwa. A raffle feels like pamigay, not surveillance. Uploading a photo feels like play, not risk.

Part of the issue is that we tend to treat platforms and apps as neutral, almost natural parts of digital life – as if Facebook, TikTok, or AI filters were simply utilities like water or electricity. We rarely pause to ask who operates these platforms, what their interests are, or what happens to our data after we click “agree.”

Another issue is that conversations around cybersecurity in the Philippines rarely include digital rights, even though many of these are already enshrined in law. The Data Privacy Act of 2012 guarantees the right to privacy, to control one’s personal data, and to demand accountability from institutions that collect it. Yet terms like “data sovereignty” or “informed consent” remain abstract for most users, even as platforms collect, store, and process massive amounts of information everyday. This gap between legal protections and public awareness leaves many Filipinos vulnerable, not because they are seldom exercised or discussed.

Beneath these everyday practices are structural asymmetries. Filipino users generate immense amounts of data that feed global advertising systems and AI models, but they have little say over how this data is used or where its value flows. Platforms operate transnationally, while local regulatory bodies remain underfunded and reactive. This mismatch shifts the burden of responsibility onto individuals, even as they navigate systems designed to profit from their participation. Like other extractive economies, data flows outward; control and profit stay elsewhere.

This isn’t naivety so much as a different way of reading digital interactions. Social scientists talk about “social trust” - how communities rely on shared relationships to navigate uncertainty. In the Philippines, this trust often extends to digital spaces: friends, influencers, and even strangers online are treated as part of a shared community. But the infrastructures that power these interactions – algorithms, data brokers, foreign tech companies – operate on logics very different from barkadahan.

Our limited sense of cybersecurity also reflects gaps in digital literacy. Many education campaigns focus on scams and misinformation. Few talk about data privacy, platform governance, or the invisible economies that run beneath our online lives. We are careful with bank accounts, but not with faces, voices, or everyday digital traces.

And yet, this isn’t simply an individual problem. Filipino users navigate a complex digital ecosystem with limited institutional support. Data breaches involving government agencies, schools, and private companies have become almost routine. Privacy policies are written in dense legalese. In this context, “cybersecurity” is reduced to what feels most immediate: avoiding scams.

To rethink cybersecurity, we need to expand the Filipino imagination of what it means to be secure online. This means treating cybersecurity not just as an individual responsibility but as a collective project: one that recognizes cultural values, but also interrogates power, governance, and rights.

Because cybersecurity isn’t just about avoiding scams. It’s about understanding how we live, trust, and participate online, and ultimately, realizing that these everyday practices are part of a bigger story about technology, power, and accountability.