Daniel Day-Lewis, pulled out of retirement by his son, finds his acting fire still burns

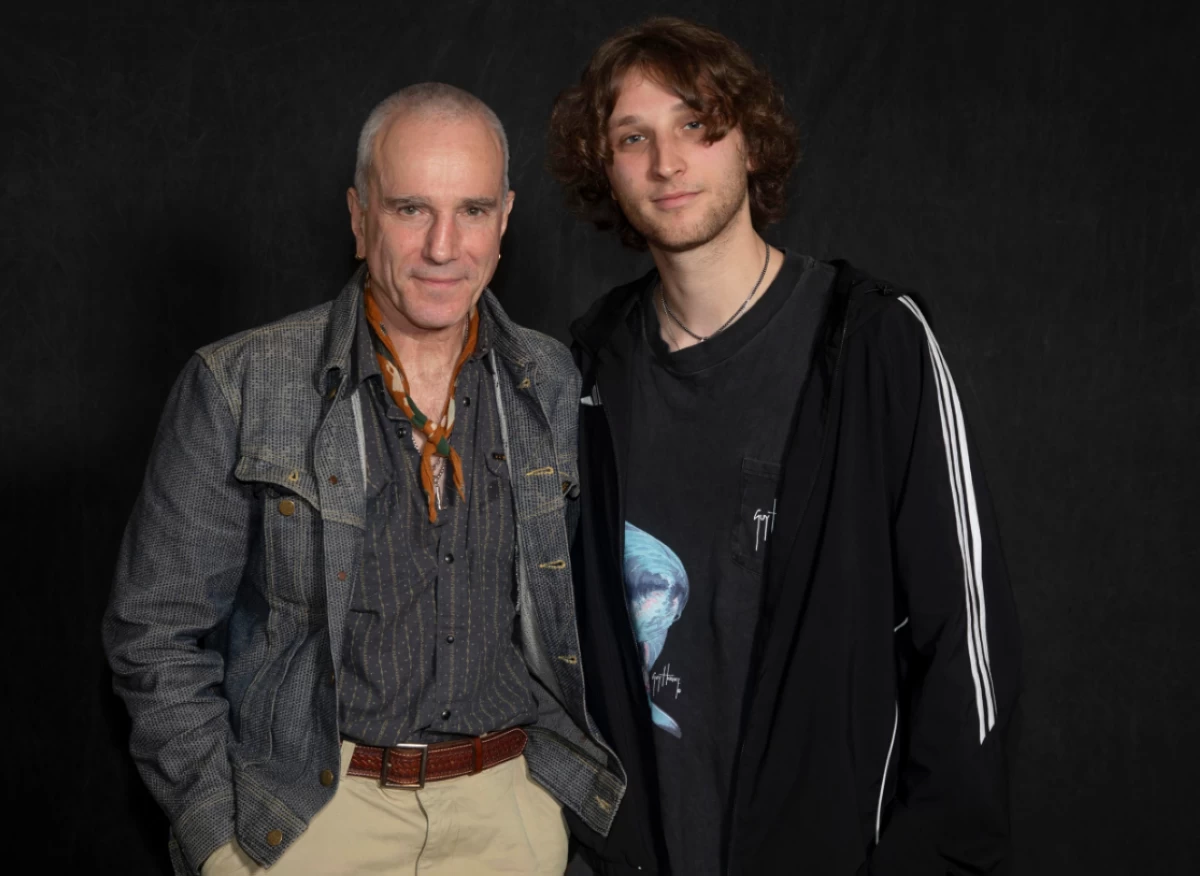

Daniel Day-Lewis and his son Ronan Day-Lewis (AP)

NEW YORK (AP) — It’s been eight years since Daniel Day-Lewis announced his retirement from acting and said he wanted to “explore the world in a different way.”

But the big-screen absence of the actor many would peg as the greatest one alive ends with “Anemone,” a new film directed by his son, Ronan Day-Lewis. The two of them wrote it together. What began as something small, with no real ambition, grew until a full feature film and Day-Lewis’ long-awaited return to movies.

“It saddened me that I had perhaps ruled myself out of that when I decided to work on something else for a while,” Day-Lewis said in an interview alongside his son. “As we progressed through it, and it seemed less and less possible to contain it, like two fellas in a shed, it began to alarm me slightly. I understood that this was going to involve the full paraphernalia of a film production, and that wasn’t something I was eager to get back into.”

“But we just kept moving forward to see what would happen,” he added. “And this is what happened.”

“Anemone,” which recently premiered at the New York Film Festival and which Focus Features releases Friday in theaters, finds Day-Lewis, now 68, not even slightly less intense or magnetic a performer. It’s a father-son story, though not an autobiographical one. Day-Lewis stars as Ray Stoker, a solitary hermit living in a remote cabin. His brother, Jem (Sean Bean), arrives and tries to convince him to return to his teenage son.

Since 2017’s “Phantom Thread,” Day-Lewis has, among other things, studied violin making in Boston. But he has also come to think of his declaration of retirement as a mistake, or not quite what he intended. At least, it wasn’t enough to stand in the way of him making a movie with his son.

“I know it’s been imagined on my behalf by numerous commentators, people that don’t know me, that somehow the way I work has left me so debilitated I can barely open my eyes in the morning. This then requires a period of five or six years recovery!” Day-Lewis says. “That was never the case. The work itself was always nourishing to me.”

Yet after making “Phantom Thread,” Paul Thomas Anderson’s London-set portrait of a perfectionist couturier, Day-Lewis was uncertain that he would ever regenerate the appetite to tackle another role.

“I definitely was brought low after I finished shooting “Phantom Thread” more than for any other reason because I anticipated being back in the public arena again,” he says. “And this is where I find myself now. And it’s something I never found a solution to from the day I started doing this work until now. The public aspect of my life I’ve always been baffled by.”

The spotlight and a ‘stark reminder’

The most meaningful gesture Day-Lewis is offering his son might not be making a movie with him, but returning to the spotlight for it. At the New York Film Festival, Day-Lewis has been a happy, humble presence, calling himself a fool for his professed retirement and dutifully accepting a glare of attention that he’s largely avoided for the last decade.

“It’s been a stark reminder for me of: Oh, yeah, that’s what it’s like,” he said, chuckling.

But Day-Lewis greeted a reporter warmly, urging him to pull a chair — a Churchill, noted Day-Lewis, a craftsman and furniture maker — and spoke candidly and thoughtfully about the mystique that has often surrounded his work, an aura he disdains.

“I knew to survive in this world that that would probably be the way I’d do it, by creating other worlds and escaping into them and living through them for a period of time,” he said. “And that remains the same. It never changed. I love that work, otherwise I wouldn’t do it. I don’t do it as an act of self-flagellation.”

Day-Lewis’ Method-acting immersion in a character has long been the stuff of legend. Jim Sheridan, who directed him in three films, including “My Left Foot,” once remarked, “Daniel hates acting.” But the idea that Day-Lewis somehow makes himself into a martyr for his art has long chafed with him.

“That’s something that’s weighed heavily over the years, this sort of misconception which has now become so ludicrous about Method acting, which is a very bad name in the business now,” says Day-Lewis. “We all find a different way of approaching the same problems. And when we’re on the set, it makes no goddamn difference what system you train under, Meisner or Method or Stanislavski or whatever it might be. You’re just there trying to live in those moments, to burn yourself up trying to find that truth as well as you can.”

Day-Lewis has sensed some of the same all-consuming imagination in Ronan, a 27-year-old painter making his directorial debut. He’s one of two sons Day-Lewis has with his wife, filmmaker Rebecca Miller. (He also has an older son, Gabriel-Kane Day-Lewis, from his past relationship with Isabelle Adjani.) From a young age, Day-Lewis saw how invested his son was in creating imagery. Ronan, meanwhile, grew up marveling from a distance at his father’s work.

“It always held a huge amount of mystery to me what he was doing,” says Ronan, who has vivid memories of being on set for films like “There Will Be Blood” and “The Ballad of Jack and Rose.” “To be inside this realm that I had always been watching curiously from the outside was so intriguing. But there were aspects of his process that still remained a mystery to me, which I think helped, actually.”

More sardines

For Day-Lewis, building the character of Ray was a step-by-step process that included everything in his woodland world, right down to the expired tin cans of sardines that line his shelves. (“There were never enough sardines for me,” he says, smiling.) “Anemone” unfolds in fits and starts, with several glorious, improvised monologues surrounded with strikingly lush imagery by Ronan. Day-Lewis so relishes pushing the boundaries of such a fictional world that, once in it, he tends to not want to let go.

“You hope to create a world, an illusion. And when somebody says to you, ‘That was the last shot. Go home now,’ that was so bewildering to me because I’m still invested in that world,” he says. “It’s not I have trouble letting go of it. The trouble I have is that I want to still splash around in that illusion.”

Still, it seems Day-Lewis has in “Anemone” avoided the kind of post-film feeling that followed “Phantom Thread.” The actor hasn’t yet announced a forthcoming project, but he acknowledges feeling the capacity for more. While he doesn’t say he missed acting during the last eight years, he appears to have come to some self-acceptance of its fundamental, irrevocable place in his life.

“It has been my primary form of self-expression for my entire life, since I was a child,” he says. “And therefore, I don’t know if I experience it as a sense of missing if I’m not doing it. But the need to express myself in that way, even at a subterranean level, that is still there.”

But just as it’s time to go, Day-Lewis offers “an appendix” to his answer. If “Anemone” has left him still hungry for more, that fact is owed partly to the nature of its making. Not just that it was done with Ronan, but that they made it, themselves. It’s Day-Lewis’ first screenwriting credit.

“And that’s a completely new experience for me,” he says. “I never really dared attempt to write before, so it’s a new thing. You can begin with absolutely nothing and the hunger can grow out of that.”