Growing up in 1940s Manila (Part Two)

How children kept themselves entertained in the past

At A Glance

- The only toys I remember having were wooden alphabet blocks, and with nothing else to do, I learned to read early.

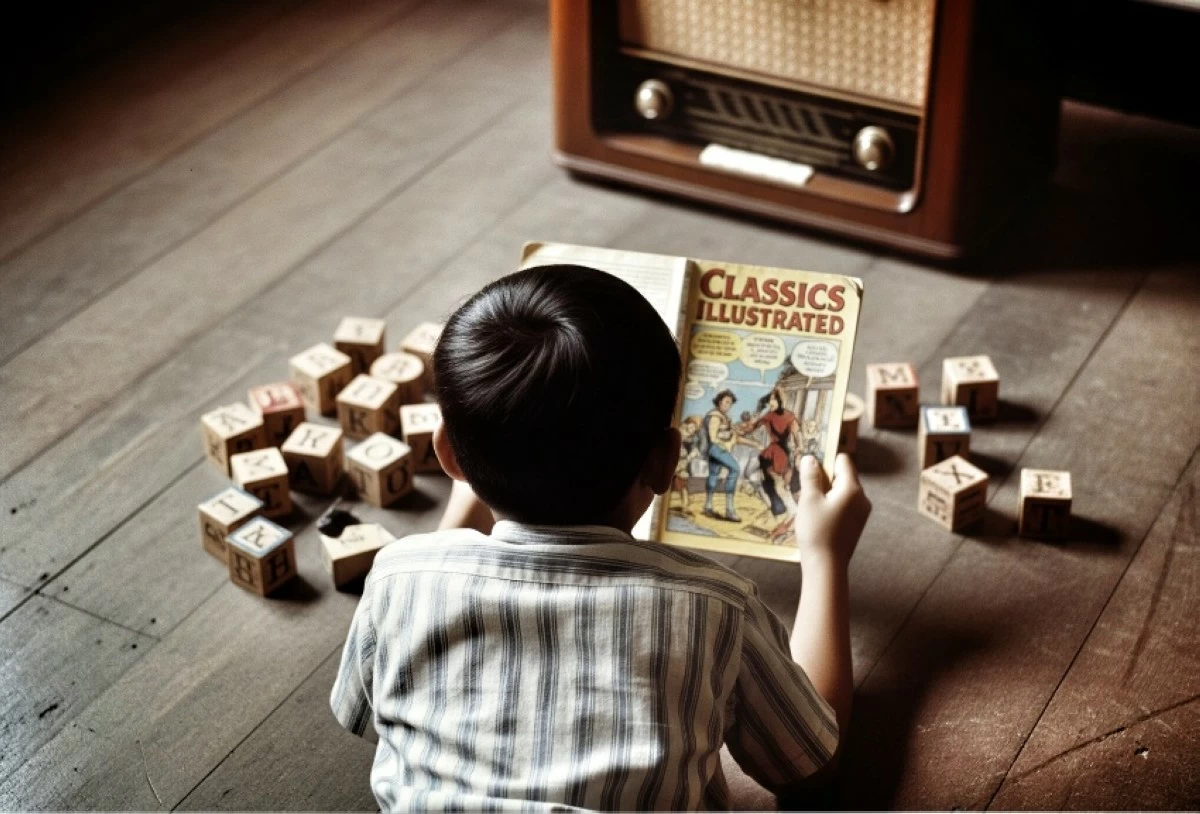

SIMPLER TIMES Kids had to find ways to entertain themselves before the arrival of television and the Internet. (Illustration by Nancy Marie Andam)

There was no TV yet, and we had a radio. The Japanese, however, censored everything. It was therefore radio silence until I was already in grade school when I would stop at a sari-sari store on Calle Economia on the way home, to listen to “Gulong ng Palad” and “Ilaw ng Tahanan.” "Ilaw’s" introductory music turned out to be Tchaikovsky (“Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini”), which got me listening to an hour of classical music every 4 p.m.

There was no telephone or computer either. People had to write, and my handwriting was awful, so Nanay got me a handwriting tutor. It was a lost cause.

The only toys I remember having were wooden alphabet blocks, and with nothing else to do, I learned to read early. Tatay had brought back from Indiana University graduate school the 12-volume “Compton’s Picture Encyclopedia,” a guide to the 1939 New York World Fair, museum guidebooks, and all kinds of other stuff. Nanay taught social studies and had a shelf of history books. I went through most of them, including the A to Z of the Encyclopedia, which made me an undisputed Trivial Pursuit champion in due course.

I spent my allowance on comic books, mainly “Classics Illustrated,” that introduced me to Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, and Silas Marner, got me around the world in 80 days, to the center of the earth, to King Arthur’s Court, and more. I also clipped the weekly illustrated notes on Philippine history published by a Sunday magazine. I wish I had kept them.

The Japanese must have thought our neighborhood was harmless, and I remember seeing only one Japanese soldier. I peeped through a crack in an upstairs window. He noticed, stopped, and demanded to know who that was. Nanay sweated, giving a long explanation that it was only me.

Times must have been truly hard. At least once, Tia Julî walked the 30 kilometers from Lola’s farm in Marilao lugging a bayongful of rice, but otherwise, everything seemed okay to me. It was different for the adults, of course. Vegetables replaced flowers. The piano disappeared, sold. Tatay built an air raid shelter—books piled on top of some planks that thankfully were never needed. The night sky glowed a pretty orange, and there were distant drum beats that were, of course, cannon fire on burning Ermita and Malate. Being near UST, which the Americans captured first, all was quiet on Karapatán. Our only excitement was the Texan soldier Joseph Slay, who was briefly billeted at home.

I was saling-pusà (age five) at Washington Elementary School and still know how to count one to four in Niponggo. When classes resumed in 1945, Tatay got me into Grade 3 at Dr. Alejandro Albert Elementary School on Dapitan Street. He walked me there on the first day, pointing out the corner here, that house there, the kangkong ditch, and was told to walk back by myself. There was hardly any traffic then, and I got home easily enough.

Albert was a two-story wood building fronting on Dapitan, the back of which all the way to Pi y Margall Street was vacant land for gardening. It must have been in Grade 5 that we boys were each assigned a plot and instructed to go farming. It wasn’t easy, shoveling and raking, weeding, hauling water often from the canal on Pi y Margall, but I was proud of my corn and peanut harvest.

Primary grades were held in assigned rooms, under Miss Nuguid in Grade 3, and Mrs. Marquez in Grade 4. I first learned maps from Mrs. Marquez. She also showed us a picture of Luna’s “Spoliarium,” and I was astounded that such a gory picture could be worth ₱30,000 (her figure) when Coca Cola was 10 centavos. I was also astounded at the rumor that at The Manila Hotel, it was one peso. Grades 5 and 6 pupils walked orderly in twos, from the arithmetic room to the English language room, etc. I tried to look modest when Mrs. Escandor read aloud my composition on my fictional goldfish—my pets were actually guppies. One time, some classmates and I walked all the way to the Insular Life Building on Plaza Moraga for Uncle Bob Stewart’s DZRH quiz show. I got called, was asked where Eskimos live, and won a fortune, all of three pesos, for screaming, “Igloo!!!”

Albert students were supposed to go on to Arellano High School near Azcarraga, but had to pass an entrance exam to qualify. I was barely 10 and Tatay wasn’t sure I’d make it. Ateneo was Plan B. He took me there, then on Padre Faura Street. “See, it isn’t too bad,” he assured me. That was comforting, but anyway, I passed.

Graduation day was in October 1949 (we were called “Octoberians”), held at Heights Theater across from the Dapitan Market near Mayon Street. The year came to a close in Baguio, at the Hi-Y Conference sponsored by YMCA. On December 26, a busload of us high school boys took off in high excitement, passing mango-tree-lined MacArthur Highway, past rice fields, and Mount Arayat, then up Kennon Road. Bridal Veil Falls was in full flow, the Bued River was clear and green, and the city was in a pine forest. We settled down on cots in the school building by City Hall, shivering and thrilled in the scent of pine.

My 1940s were simple years, happy times.

Notes: Dr. Alejandro Albert Elementary School now has 234 air-conditioned classrooms, 10 elevators, a gymnasium, and an auditorium on the eighth floor. A large lawn is at the center of the U-shaped building, with no corn or peanut plants in sight.

Comments are cordially invited, addressed to [email protected]