A fresh addition to Kapitolyo’s creative hub, Colab Café has officially opened as both a coworking space and a gathering place for ideas. With its industrial-chic interiors, abundant natural light, and even a full material library, the café offers freelancers, entrepreneurs, and especially creatives a productive spot to work and connect. More than just a caffeine stop, Colab Café aims to be a venue where conversations flow as freely as the espresso.

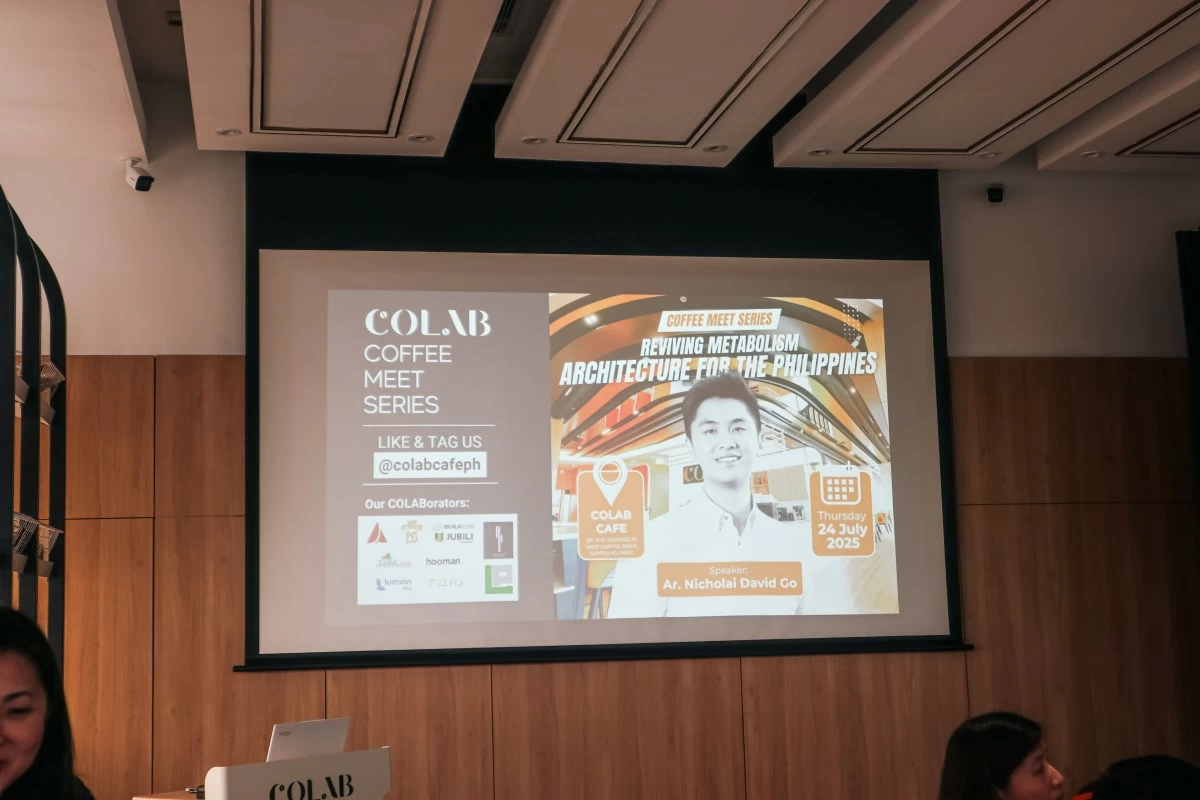

In collaboration with leading architects and interior designers, the café has recently launched their "Coffee Meets," a biweekly seminar series focused on Philippine architecture and design. Each session delve into topics such as heritage preservation, sustainable building, and contemporary design trends, providing an open platform for dialogue between professionals and enthusiasts alike. Organizers hope Coffee Meets will nurture a deeper appreciation of the country’s architectural identity while sparking fresh ideas for the built environment.

Last July, I had the privilege to speak at Coffee Meets on behalf of Pino Places and Manila Bulletin's Pino Perspectives. For my seminar, I introduced myself by sharing my personal journey with design—from starting a gelato business in high school, to studying architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design, to leading one of the top kitchen, laundry, and steel fabrication companies, and founding Pino Design Studio. My career has taken me through many different industries, but I’ve learned that architecture is not just about buildings—it’s about designing systems, experiences, and communities.

The heart of my talk focused on two concepts I believe are essential to defining our true Philippine architecture: Bayanihan and Metabolism. Bayanihan, our deeply rooted tradition of communal unity and cooperation, once shaped the way Filipinos built and lived—from the portable, flexible Bahay Kubo to shared public spaces that reinforced social cohesion. Sadly, colonial history and modern privatization have eroded these values, but I believe that by reviving Bayanihan as a design principle, we can rebuild communities that are more cooperative, inclusive, and resilient.

Metabolism, on the other hand, is a Japanese architectural movement that emerged after World War II, emphasizing flexible, modular, and sustainable designs that grow and adapt like living organisms. While it is a foreign concept, I see strong parallels with our own communal traditions. Combining Bayanihan’s cultural spirit with Metabolism’s adaptability could lead us to a uniquely Filipino architectural identity—one that is rooted in tradition yet prepared for the future’s uncertainties.

To show how these ideas could work in practice, I shared my ongoing project, EqualiWell, a healthcare system designed to be both resilient and equitable. It uses mobile health units that can adapt to outbreaks and natural disasters, bringing dignified care directly to communities in need. For me, this is just one example of how design can address larger systemic challenges.

I closed my talk with a belief I hold dear: “Everything designed, can be redesigned for the better.” I am never satisfied with how things are and believe that I can design things better. I invite all of you to have that same mindset. Great architecture is not just about great buildings—it’s about building a better society.

Check out Colab Café's ongoing Coffee Meets series by visiting their social media channels. It is a great place to not only learn from industry professionals but also meet other like-minded creatives and designers.