‘Love According to the Plants (Na May Breeding)’ celebrates 50 years of UPLB’s Institute of Plant Breeding

In a nation where food security remains a pressing challenge, the science of plant breeding has emerged as a quiet yet powerful force shaping our collective future. At the forefront of this effort is the University of the Philippines Los Baños Institute of Plant Breeding (UPLB-IPB), which celebrates its golden anniversary this year.

Established in 1975, the IPB has been a pioneering institution whose impact stretches from local farms to international fields, developing new and improved crop varieties for progressive agriculture.

But this celebration is more than a scientific milestone. In a deeply resonant interplay of science and art, this anniversary was complemented with a stage play titled “Love According to the Plants (Na May Breeding),” written by acclaimed playwright and Palanca-winning writer Dr. Layeta P. Bucoy. The play highlighted the value of plant science as a compelling narrative that humanizes scientists and dramatizes the unseen labor that helps put food on our tables.

Play rooted in science

“One of the major goals of plant breeding is to feed people,” Bucoy explains. And yet, to the public, plant breeders often remain anonymous, their achievements tucked away in academic journals and laboratories.

Through theater, Bucoy brings their stories to light. “Love According to the Plants” is an unusual title, but beneath the romantic metaphor is a scientific truth: breeding—whether of plants or relationships—requires patience, compatibility, and vision.

The play depicted real scientists such as Dr. Nemesio Mendiola – considered the “Luther Burbank of the Philippines” – who authored “A Manual of Plant Breeding for the Tropics” in 1926 and National Scientists like Dr. Dioscoro Umali (Father of Plant Breeding in the Philippines) and Dr. Ramon Barba. The play featured Dr. Barba’s work on banana tissue culture, which not only benefits the Philippines but other countries as well.

There’s also Dr. Ruben Villareal, who made a cameo in the play. He was responsible for the discovery of the non-Mendelian or cytoplasmic inheritance of the southern leaf blight disease of corn. His discovery even benefited the US corn industry. There’s also Dr. Azucena ‘Susie’ Carpena who developed several varieties of cassava not only for food (reducing the toxic Hydrocyanic Acid or HCN) but also for industrial purposes as well like fermenting its roots for alcohol.

Through an ensemble cast of fictional and historical characters, the play explores how scientific knowledge is passed on like genetic material, sometimes methodically, sometimes by accident but always with the intent to preserve and evolve. A talking munggo, inspired by a suggestion from Dr. Dolores Ramirez (National Scientist for Biochemical Genetics and Cytogenetics who served as technical consultant for the play), adds a whimsical yet educational layer to the narrative, symbolizing both the fragility and resilience of life.

“Dr. Ramirez said it would be nice to have a talking munggo sharing its travel adventures. When I asked how it can be possible for a munggo to survive for years (it only has a lifespan of 60 to 90 days), she came up with the probability—store it in a gene bank and when replanted, it will maintain its genetic composition.”

Love, hybrids, and metaphors

In “Love According to the Plants,” the playwright cleverly draws parallels between plant hybridization and human relationships.

“When two individuals fall in love, their bond becomes a hybrid of their desired traits,” she explains. Just as breeders cross genetic lines to create stronger plants, people form partnerships that evolve through conflict, compromise, and care.

This central metaphor lends emotional resonance to what might otherwise be abstract science. And that is precisely Bucoy’s gift—her ability to locate the human experience at the heart of science. In doing so, she demystifies complex topics like micropropagation, cytoplasmic inheritance, and spontaneous mutation, making them accessible and engaging to audiences of all backgrounds.

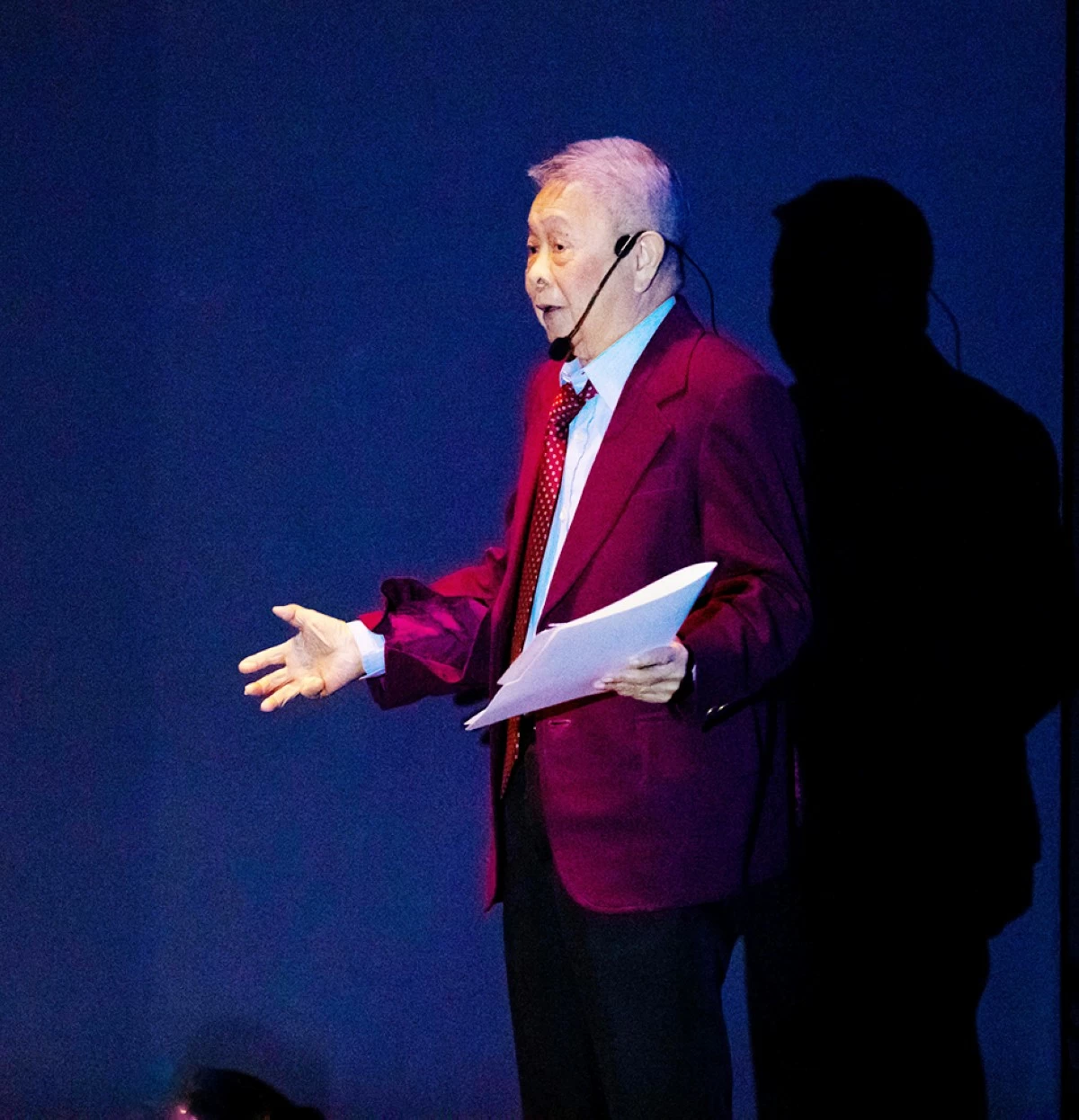

“There were scientists who expressed their appreciation and enjoyment after watching the play. Those who are not into science were quoting several scientific terms used in the dialogues. The most surprising response for me came from National Scientist Dr. Emil Javier. I knew he’d appreciate the play because he was instrumental to the establishment of the IPB. But what surprised me was how excited he was in sharing his favorite subplot and actor. It was not even the story arc on Corn T-cytoplasm where his friend Dr. Villareal made a cameo, but the one on cassava where he said one of the student actors shone best.”

The play does not shy away from thorny issues either. Themes of ambition, grief, injustice, and even class inequality are interwoven into the narrative, mirroring real-world challenges faced by scientists. Research, after all, does not occur in a vacuum as it is shaped by politics, funding, public perception, and policy.

Science beyond the lab

For Bucoy, this theatrical experiment is part of a larger advocacy: to bridge the gap between science and society. “Science aims to be objective, but the act of communicating it requires empathy and imagination.”

She is not alone in this belief. Historically, the theater – or art in general – has always been a site for scientific inquiry. “Ancient Greece already blended science, art, and philosophy into a unified system. Our babaylan (according to historian Dr. Zeus Salazar) was ‘expert in literature, religion, history, and other sciences.’ And if we are to believe Brecht, artists must use one or two sciences for ‘the great and complicated things that go on in the world cannot be adequately recognized by people who do not use every possible aid to understanding.’”

Plays like Kapek’s “R.U.R.” (which gave us the word “robot”), Brecht’s “Life of Galileo,” and Frayn’s “Copenhagen” have shown how scientific progress is not just technical but also ethical and emotional. Bucoy's work joins this lineage, but with a uniquely Filipino perspective.

In fact, she has made it her mission to dramatize the actual research outputs of Filipino scientists, translating jargon into narrative, data into drama. Her earlier works on global warming, biotechnology, and nanotechnology have been used in classrooms, proving that science-art interplay (or perhaps, science storytelling) can indeed spark interest in STEM fields, particularly among younger audiences.

“I learned that one of my plays, ‘The Adopted Healthy Baby,’ based on the research of Dr. Milagros Peralta on evaporation suppressant, was required reading for Grade 11 in some schools,” she shares. “So, it’s possible that ‘evaporation suppressant’ entered their vocabulary through a play.” And that, perhaps, is an achievement: when science is not just understood but remembered.

Celebrating a legacy

As the IPB celebrates 50 years, it’s laying the groundwork for the next 50. The challenges ahead are immense: feeding a growing population, adapting to climate change, preserving biodiversity, and ensuring equitable access to nutritious food. These cannot be solved by science alone, nor by art in isolation, but perhaps by the two working together.

The interplay of science and theater reminds the audience that behind every breakthrough are human stories filled with curiosity, failure, resilience, and hope. That every hybrid seed planted is an act of faith in the future.

Bucoy is already planning her next works: a series of plays on the lives and works of National Scientists, starting with the Father of Plant Breeding in the Philippines. In doing so, she continues to sow the seeds of knowledge, empathy, and imagination.

After all, whether in the lab or on stage, one thing remains true: it all begins with a seed of an idea.