Philippine peso still the worst performer in region

The Philippine peso continued to depreciate the worst among Asian currencies since the Israel-Iran war started, according to Japanese financial giant MUFG Bank Ltd.

In a June 20 report, MUFG Global Markets Research noted that last week, “we saw a mild rebound of the United States (US) dollar (DXY index) by 0.5 percent due to safe haven flow given the rising geopolitical conflict between Israel and Iran.”

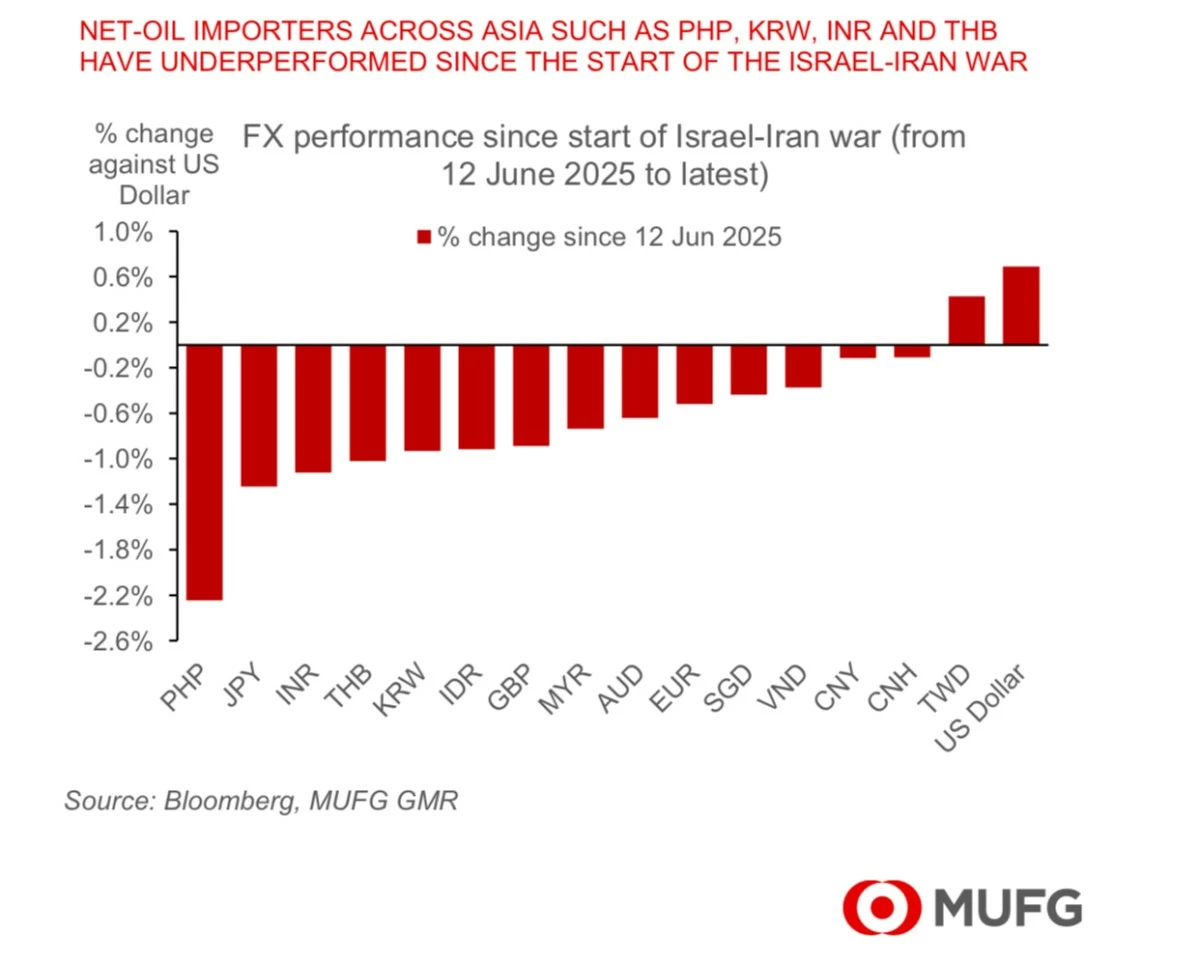

“As a result, almost all Asian currencies posted a loss against the greenback, with the Philippine peso underperforming the most in the region,” MUFG said.

Since Israel attacked Iran two weekends ago, the peso weakened by 2.2 percent to date, versus the US dollar, from June 12 levels.

MUFG noted that net oil-importing currencies like the peso, South Korean won, Indian rupee, and Thai baht all underperformed since the Middle Eastern conflict escalated.

“We think there’s a good chance the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) will start to intervene more aggressively if Philippine peso weakness continues unabated towards the ₱58-₱59 levels within a short space of time,” MUFG Global Markets Research senior currency analyst Michael Wan said.

While MUFG had forecast the peso to end 2025 at the stronger ₱54:$1 level, it said that “we’ll likely have to adjust our Philippine peso forecasts weaker if oil prices and geopolitical premia continue to rise.”

The Japanese bank’s estimates “suggest that every $10 per barrel rise in oil prices boosts the Philippines’ current account deficit by 0.4 percent of GDP [gross domestic product],” putting pressure on the peso.

“With the Philippines current account deficit already quite large at 3.5 percent of GDP in 2025 due to infrastructure and capital goods import needs, this deficit could easily rise above four percent of GDP if oil prices were to rise further, with the change at the margin being the external oil price shock, and as such making it more difficult to finance the current account deficit even with our expectation of FDI [foreign direct investment] increases,” MUFG cautioned.

In particular, MUFG warned that the deficit in the current account, or net dollar earnings, may climb to 4.5 percent of GDP if global oil prices soar to $90 per barrel.

The latest BSP data had shown that the Philippines’ current account deficit doubled to $4.2 billion in the first quarter of 2025 from $2.1 billion a year ago, as goods imports growth outpaced the rise in exports.

The Philippines is a net importer of the goods it consumes. Economists are bracing for a surge of products coming from China—already the top source of Philippine imports for many years now—as Chinese exporters look for alternative markets other than the US amid renewed trade tensions between Beijing and Washington.

BSP data showed that the current account deficit’s share to GDP climbed to 3.7 percent at end-March from 1.9 percent a year ago.

The BSP had projected the current account deficit would further widen to $19.8 billion, or 3.9 percent of GDP, this year.

Last year, the deficit stood at $17.5 billion, or 3.8 percent of GDP—larger than the $12.4 billion, or 2.8 percent of GDP, in 2023.

Uncertainties around oil prices in the aftermath of Israel’s attack on Iran also increased Philippine government bond yield spreads with the US at the fastest pace in the region, with the two-year yield rising by four basis points (bps), and the 10-year by five bps, MUFG noted.

After last week’s 25-basis-point (bp) reduction in the policy interest rate to 5.25 percent, MUFG expects the BSP’s policy-setting Monetary Board (MB) to cut 50 bps more before year-end amid easing inflation, even as the central bank “could be constrained in an oil price shock scenario.”

Nonetheless, the BSP “appears to be willing to tolerate some peso weakness in the near term amid global risk aversion,” MUFG said.