Max Balatbat’s latest solo exhibit, “Sampalataya,” running until May 31 at the Art Cube Gallery, is his homecoming. The exhibit is a raw and unflinching look at the crucible of faith, forged in the very neighborhood in Caloocan that shaped him—a place where desperation was a daily companion, yet in prayer, in its most unvarnished forms, always found a way.

At A Glance

- The exhibit shows that faith isn't a monolithic, pristine concept but a messy, human negotiation with the divine, often driven by immediate needs and desires.

"KAPILYA," mixed media on canvas, 284cm x 640cm, 2025.

MEET THE ARTIST Max Balatbat

Max’s art is deeply rooted in his childhood memories. He recalls his family building a small, unassuming chapel in the heart of the chaos. It wasn’t about grandeur or institutional sanctity. It was a gathering point where neighbors, prostitutes, gun-for-hires, drug lords, laborers, and mothers came as they were, offering prayers for safety, success, or simply something to cling to.

The exhibit shows that faith isn’t a monolithic, pristine concept but a messy, human negotiation with the divine, often driven by immediate needs and desires.

Questioning the fabric of belief

The title “Sampalataya (faith or belief)” is a deliberate question for Max.

“Isang malaking katanungan ang pang-unawa ko sa salitang ‘sampalataya’ (My understanding of the word ‘faith’ is a big question),” Max says. “I grew up in the chaotic corners of Caloocan, surrounded by people who were ‘halang’ (wicked). I saw how they practiced their faith, like pimps praying to sell more flesh, prostitutes praying for more clients, drug pushers praying for successful transactions, killers praying for targets, gamblers hoping to overturn the bank. Whether positive or negative, our prayers and beliefs are all the same.”

"KONTRA 002," mixed media on canvas, 168cm x 88cm, 2025.

Growing up in Caloocan provided Max with a unique lens through which to view faith. He describes his childhood environment with stark honesty—”magulo, madumi, madilim, maliwanag (Messy, dirty, dark, and bright), a place of prostitution.”

“There were no quiet nights, only celebrations like a fiesta,” Max says. “We all had faith in the patron saint named La Medalla Milagrosa. I was an altar boy, not because of faith, but for the pocket money from my grandmother, who built the chapel in our area, in the middle of the third corner of the avenue.”

He also revealed that while serving as an altar boy, he encountered tension between outward devotion and inner truth, showing how the exhibit will challenge its viewers to confront the raw, unadulterated reality of belief.

“But I prayed, I asked for forgiveness sometimes, I wished upon statues, but I didn’t change and pretend to be a good person,” the artist muses. “I felt that the ‘pious’ people in our area were hypocrites, pretending to be holy, worshipping idols to go to a ‘heavenly heaven.’ That’s why for me, hubad lang ang sampalataya (faith is naked). Wounds, scars, stench, dirt… Bring them out. What you worship isn’t stupid. It’s vast and will understand you.”

"MANONG DRAYBER," salvage antique religious head, vintage steering wheel, bulyos, resin, dimensions variable, 2025.

Pain as prayer

A pivotal influence on “Sampalataya” is Max’s recent immersion in a cenaculo, a traditional Passion where participants reenact Christ’s sufferings, sometimes engaging in self-flagellation. Max chose not to be a mere spectator. His direct involvement profoundly impacted his vision for the exhibit.

“Since I was a child, it was always a question for me why they did it. Every Holy Week, my father would take me to Pampanga to watch the penitents,” Max recalls. “Now, I take my children so they can understand. I was always told when I was young, ‘It lessens sin.’ They said it was asking for forgiveness, so I went back and studied everything. I asked around and investigated. I learned from the penitents that it wasn’t about lessening sin, but rather a vow to make a wish. Wishes for prosperity, healing, food, money, wishes always for their family, especially their children.”

This understanding led him to participate as well. “Last Holy Week, I suddenly thought of doing it to completely understand everything. I went through the necessary process, walked in the midday heat, lashed here, lashed there, and knelt in front of the chapel. My mind was blank, no wishes, just questions and feelings. Afterwards, I suddenly understood them. For me, it’s a performance and an act that has become intertwined with their customary belief,” he concludes. “I was able to answer some questions, some speculations in my mind became clearer, and I understood more about what they call ‘panata’ (vow). But I’m happy I tried and experienced the stinging, pain, heat, hardship, and fatigue. Now I understand them more.”

This visceral experience of shared ritual pain, suffering as currency, pain as prayer, is shown in the exhibit’s visual language and the palpable “weight” of Max’s pieces.

"NUEBE," mixed media on canvas, 87cm x 60cm, 2025.

Unpacking ‘Sampalataya’

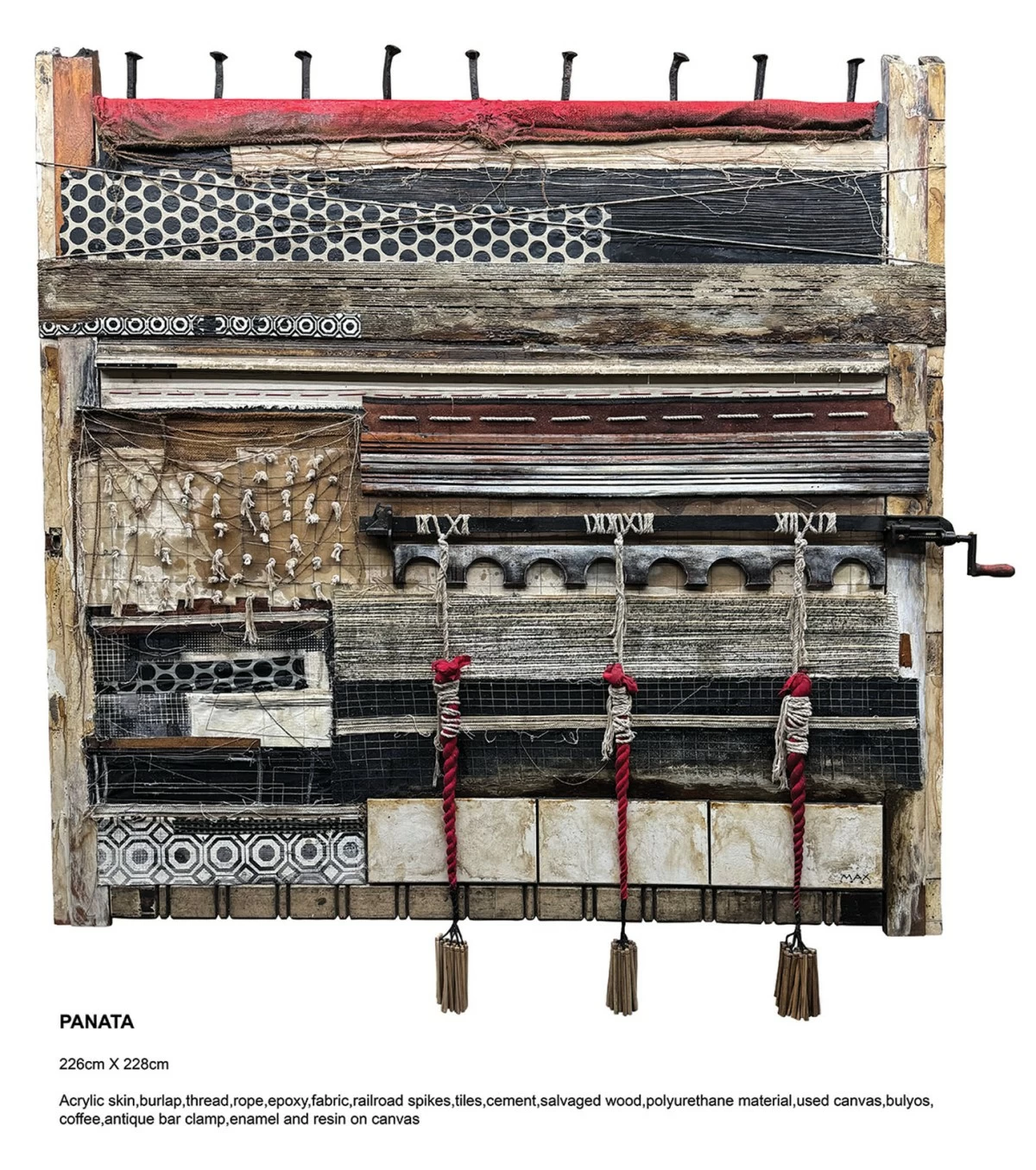

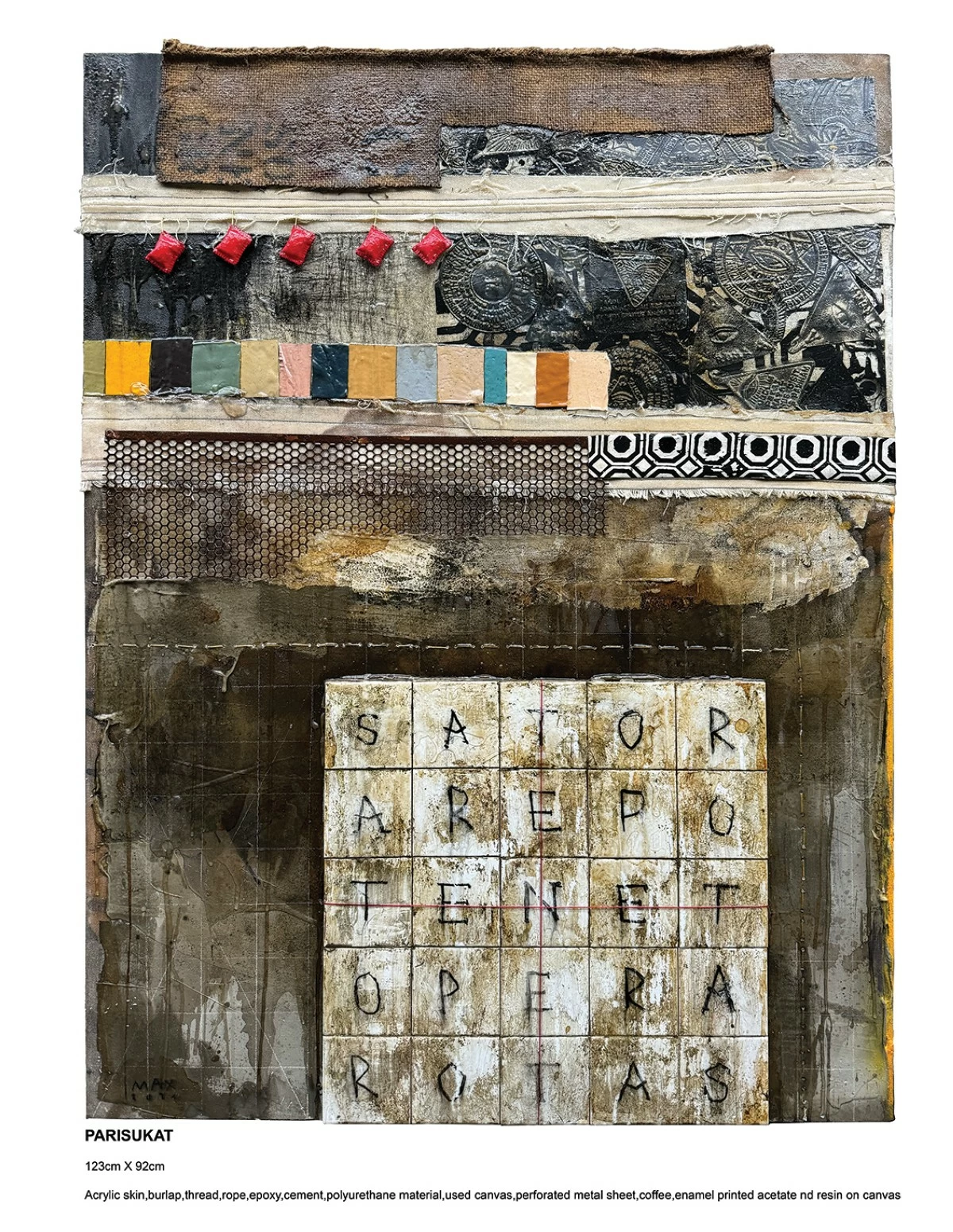

Max’s work is renowned for its materiality. He uses burlap, pillow stuffing, railroad spikes, salvaged wood, used canvas, rope, tiles, and cement—elements that carry the stories of their origin and previous lives. For him, “a work must have layers and scars, it must carry weight.” This philosophy is evident in “Sampalataya,” where textile patches resemble bandages, as if each artwork attempts to dress a wound that still bleeds. His raw use of materials like acrylic skin, epoxy, enamel, and a coffee-stained canvas speaks to a refusal of pretense or purity.

His creative process was remarkably uninhibited. “This time kasi walang isip-isp, wala ng kwento-kwento, basta bira lang ako ng bira (This time there was no thinking, no stories, I just give what I’ve got). The more wrong, the more right. The dirtier, the better. The more brutal, the truer. It was hard, but it felt satisfying,” Max says. “When I finished the pieces, I saw that they were telling a story. I’m just happy because the pieces are speaking and shouting, and I no longer need to tell the story.”

When it comes to selecting materials, Max reveals a deep affinity for salvaged objects. “Mahilig lang talaga ako mag-ipon mga bagay-bagay (I just enjoy collecting things). Sometimes for years, sometimes decades. The wounds of wood, the rust of metal, the stains on fabric, leftover threads from sewing machines. What others see as wrong, I see as beautiful. They are so real, no hiding. Door frames worn down from opening and closing. I gave them new value. Discarded wood and metal, they speak of stories from yesterday. Torn and tattered fabric scraps, they shout beauty in every piece. The wrongs and scars of the past are naked stories that must be seen.”

"PANATA," mixed media on canvas, 226cm x 228cm, 2025.

The naked truth of faith

When asked what he hopes viewers will take away, Max’s answer is direct and universal, “Ang pagsampalataya ay walang relihiyon (Faith/belief has no religion).” It’s a powerful invitation to consider belief beyond institutional boundaries.

The challenges in creating this exhibit were intrinsically linked to his process. He sees his work as solving a puzzle, connecting dots. The questions he had were answered through the creative act itself.

“Perhaps the questions just answered themselves,” Max says. “The speculations just unfolded on their own. The long periods of collecting materials just naturally settled. The hardship was there, but the feeling of joy when it was finished was clearer.”

Ultimately, it was Max’s honesty that made the exhibit so transparent. “I was also true to the story and the making, so everything became quite free. Perhaps the biggest thing I learned is the value of time. There’s nothing wrong with what you’re facing now, perhaps your value will only be realized tomorrow or the day after.”

"PARISUKAT," mixed media on canvas, 123cm x 92cm, 2025.

“Sampalataya” is an experience that demands honesty from its viewers, just as Max has been unflinchingly honest in its creation. It invites viewers to look past the superficial and find the profound, often difficult, truths woven into the fabric of human faith.

“Sampalataya” runs until May 31 at Art Cube Gallery, OPVI Centre, Chino Roces Extension, Makati City.