As first case arrives in PH, should you be worried about mpox?

How big of a threat is the monkeypox outbreak?

By DR EDSEL SALVANA

On Aug. 14, 2024, the World Health Organization declared a new Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) due to an outbreak of mpox (previously known as monkeypox) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and some of its neighboring countries. This is the third PHEIC in the last four years and is indicative of how infectious diseases are increasingly becoming a threat to humanity. Shortly after, on Aug. 19, 2024, the Department of Health announced the first local case of mpox this year in a 33-year-old male with no history of recent travel outside the country. There is a possibility the patient may have acquired mpox through sexual transmission but the details remain unclear. This is the tenth case of locally confirmed mpox in the Philippines since 2022. Genomic sequencing is ongoing to find out if this is part of the new mpox PHEIC, or if this is just a sporadic mpox case from the previous PHEIC.

Last July 2022, just as the Covid-19 pandemic was finally winding down, another PHEIC was declared. The culprit was not a novel virus but an old one. Mpox, caused by the monkeypox virus (the virus name has not been changed), has been known to cause outbreaks in Africa, especially in areas of Central and West Africa. It was first discovered in infected monkeys in 1958 (hence the name) and the first human cases were described in the DRC in the 1970s. Epidemics outside Africa have been documented and ultimately traced to recently returned travelers or from infected animals imported from endemic areas. We had four local cases of mpox in the 2022 outbreak, all of whom recovered.

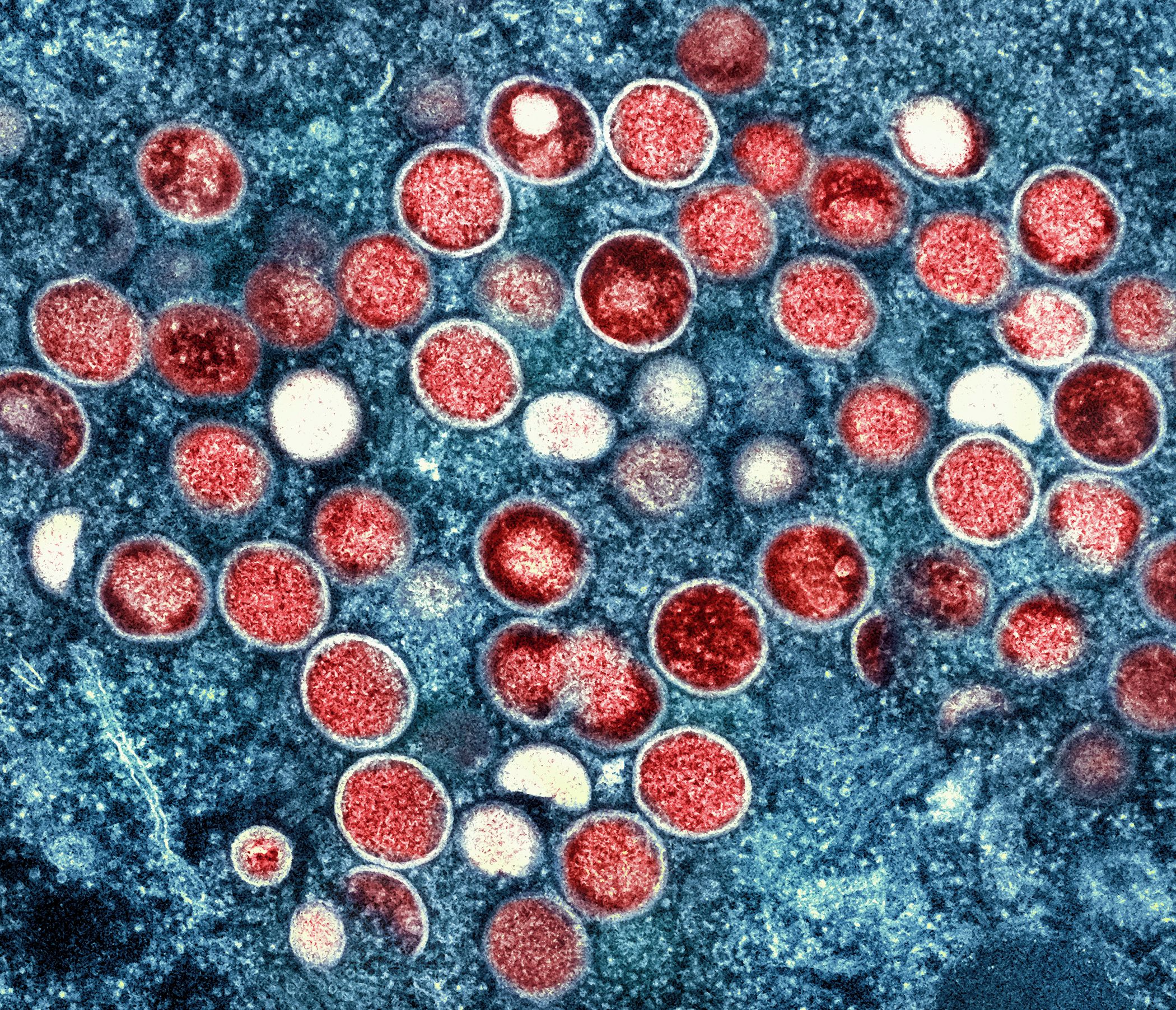

The monkeypox virus is in the same family as the smallpox virus. It causes vesicular (blister-like) lesions all over the body that evolve into pustules and can easily be mistaken for smallpox. Many animals can be infected and have served as vectors and reservoirs for human infection. The virus has been classified into two clades, similar to variants in Covid-19. Clade I is the deadlier of the two and is found in the DRC and surrounding countries. Mortality rates can reach more than 10% especially in elderly and immunocompromised populations. Clade II is typically found in West Africa and is less deadly with a mortality rate of about 0.1 to 3.6 percent. Most imported cases, including the 2022 PHEIC, were from clade II, specifically clade IIb. The 2022 PHEIC was unusual in that the predominant mode of transmission was through sexual intercourse. Prior to that outbreak, mpox was not thought to be a sexually transmitted disease.

The last mpox outbreak in the United States prior to the 2022 PHEIC had been in 2003 when infected prairie dogs kept as pets infected humans in Milwaukee and Chicago. I was an internal medicine resident at the Froedtert Hospital in Milwaukee at that time where a few of the cases were diagnosed, and I recall that there was a huge fuss over it. Thankfully, of the 70 people who got infected, no one died. The lesions that the patients had were very similar to smallpox and this cause a brief bioterrorism scare since the US was still recovering from the mailed anthrax scares in the aftermath of 9-11. The ultimate source of infection of the prairie dogs was presumed to be Gambian pouched rats imported from Africa.

The current mpox PHEIC is being declared due to an unusually large increase in cases in the DRC and its surrounding areas. The outbreak is primarily caused by the deadlier clade I virus, specifically clade Ib. However, some clade II infections have also been detected. There is evidence that clade Ib is being sexually transmitted, just like the 2022 clade IIb. This is the first time that clade I has ever been shown to be transmitted via this route. Aside from sexual transmission, mpox can also be transmitted via direct contact with the lesions and by respiratory droplet inhalation, now termed short-range airborne transmission. A person remains contagious until all the pustules have crusted over.

The incubation period of mpox is usually three to 17 days from the time of exposure but has been reported to be as short as one day to as long as over four weeks. Usual symptoms are fever, fatigue, muscle pain, sore throat, and swelling of the lymph nodes although some patients may feel fine. A rash that eventually turns into a vesicle then into a pustule can appear all over the body and can take up to two weeks to fully heal. Some patients may have just a few vesicles, and in the case of sexually transmitted mpox, these may be localized to the genital or perianal area. These can be mistaken as genital herpes, and so patients should report any recent travel to outbreak areas when they see their doctor.

Most mpox infections are mild, especially in healthy people. Many will recover on their own without the need for hospitalization. Mpox can be deadly in immunocompromised or elderly persons. Treatment is most often supportive. An antiviral called tecovirimat has been shown to work against mpox but is not available locally. Some patients can develop complications including encephalitis and post-viral pneumonia and these may need inpatient care.

There are two vaccines that are effective against mpox. These were originally intended against smallpox but have been shown to be safe and effective against mpox. The vaccines contain live attenuated cowpox (Vaccinia) and not smallpox (Variola). Vaccination for the general public isn't recommended at this time since the overall risk remains low. During the 2022 outbreak, the vaccine was administered to certain high-risk populations in outbreak areas in the United States and was quite effective in halting transmission. The smallpox vaccine should only be taken if advised by a doctor. Since it is a live vaccine, it is usually not recommended for immunocompromised people, and there is a small risk of developing cowpox (not smallpox) disease even in the general population. The Department of Health will determine if a vaccination program becomes necessary, but it will likely be highly targeted towards high risk and vulnerable populations.

Mpox is not as contagious as Covid-19 and there is already an effective vaccine. It is unlikely that any pandemic restrictions will need to be brought back unless there is a big outbreak. Surveillance measures are in place and incoming travelers are being monitored. If you think you have been exposed to mpox or you have symptoms that are consistent with mpox, contact your doctor immediately and isolate yourself at home. Testing is available at the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine and can be arranged by the Department of Health. For elderly and immunocompromised persons, wearing a mask can decrease the risk of transmission. For everyone else, good hand hygiene, safe sex practices and avoiding travel to outbreak areas can help mitigate the risk.

If the current mpox patient turns out to be clade IIb, this is likely leftover transmission from the 2022 mpox PHEIC since it never really disappeared and sporadic clade IIb transmission continues to occur in different countries. If this is clade Ib, it will be the first ever in our country and there is a greater potential for harm. Reminding everyone to stick to the public health standards of hand washing, judicious mask use and continued vigilance will work very well against this virus. This is not a respiratory virus like COVID-19 and its spread can be better controlled. The 2022 mpox PHEIC ended in less than a year, and if everyone does their part, the current one shouldn’t last very long either.