How plastics worsen floods, emissions

Anyone can draw a line from plastics to floods. In the recipe of murky urban floodwaters, plastic products are a staple ingredient. Labo or sando bags, bottles, food containers, and sachets—you name it, you can find them bobbing along rushing floodwaters during typhoon season.

Suffocating our drainage systems, plastic waste makes floods worse. A 2023 report commissioned by Tearfund confirms this: Plastic pollution increases the risk of severe and frequent flooding in poor communities.

Not that Filipinos need any reminders.

Drawing a line between plastics and flooding

Many videos of the Typhoon Carina-enhanced "habagat" floods showcase the pollution problem—people wading through chest-high waters, with plastic bottles and bags floating around them. Days after the rain stopped, residents from affected areas still cleared trash off their streets. Water damage to their homes aside, residents’ health is also at risk from prolonged exposure to waste.

Much of this plastic is thrown into canals, clogging storm drains, and sewers. Last week, when the waters rose because of the non-stop downpour, the trash rose with it.

Dire as the situation is, it is not new—it did not appear overnight. In fact, the issue of plastic pollution and waste disposal has long been intertwined with flood management discussions.

No less than President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. himself expressed this when he conducted an on-ground inspection of the devastated communities, urging Filipinos to practice proper waste disposal so the installed flood pumps could work effectively.

The connection is clear: Plastic pollution exacerbates flooding, and in turn, increases the damages floods cause. But one line many Filipinos have yet to draw from plastics to floods runs through climate change.

Putting two and two together

In every step of their production and its eventual disposal, plastic products heat the planet in various ways.

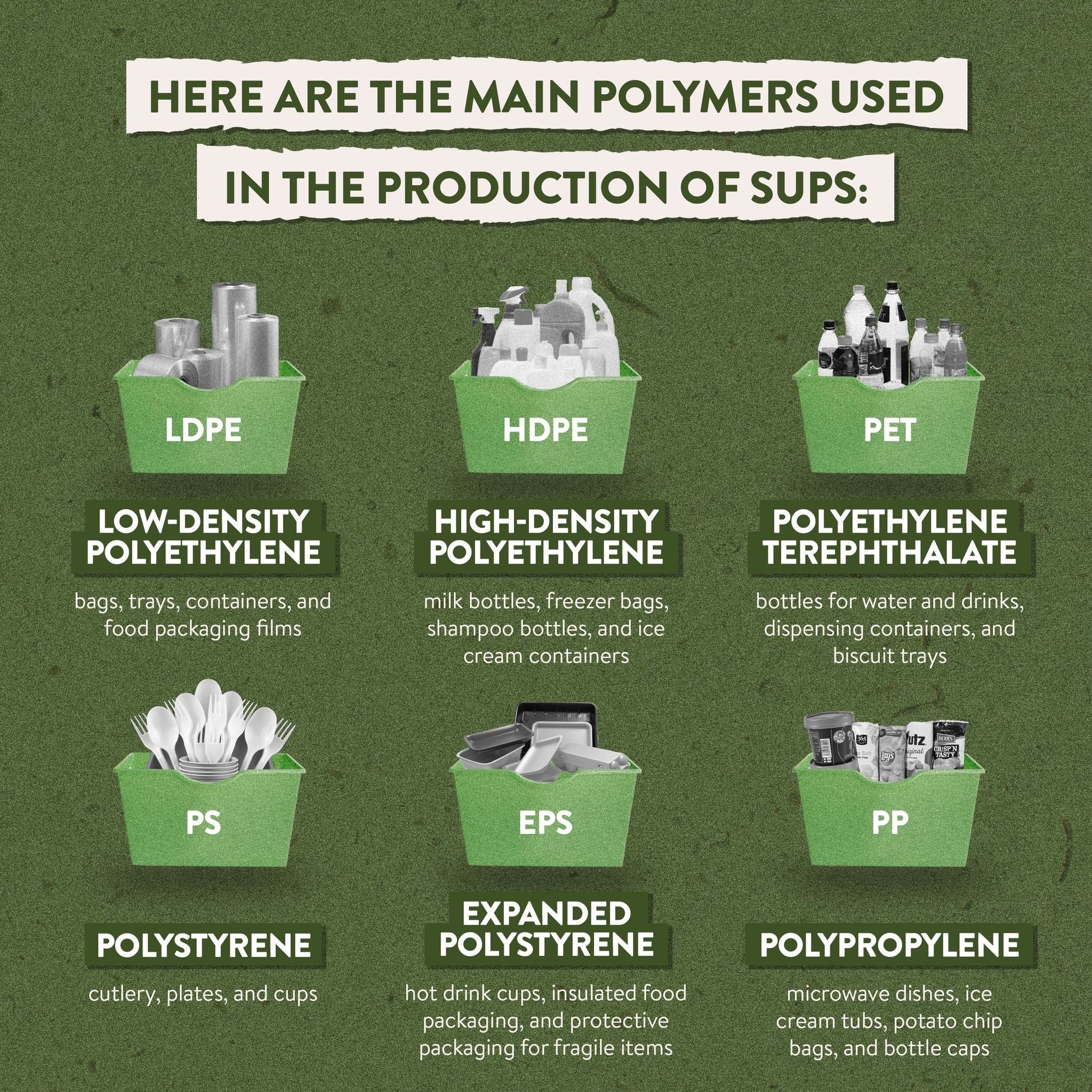

For example, at the production stage, 99 percent of plastic products are made from petrochemicals. These are derived from fossil fuels like oil and natural gas. To process these materials, more fossil fuels are consumed, which then adds to the already alarming amount of greenhouse gases across the planet.

Greenhouse gases, in turn, accumulate to trap heat in the atmosphere by absorbing and reradiating heat from the sun. This then leads to what the world now experiences as global warming.

Climate change is linked to extreme weather events like prolonged heat waves and super typhoons. The hotter the planet becomes, the stronger typhoons it produces. As typhoons get stronger, floodwaters grow higher—to the detriment of climate—vulnerable nations like the Philippines.

What at first might be largely attributed to pollution, worsening floods can also be traced back to plastic production and consumption.

The line that connects the two does seem blurry, long, and complex, but it is there. This line grows more apparent when considering that plastic production is estimated to be responsible for 3.3 percent of greenhouse gas emissions.

For comparison, the world emits around 54.6 billion tons of greenhouse gases annually; 1.8 billion of which is attributed to plastic production. A ton is equal to 1,000 kilograms, which then means that the plastic industry produces 1,800,000,000 kilograms worth of greenhouse gases.

With that much contribution to global warming, and in turn, to stronger typhoons and worse floods—is the line clearer now?

Seeing the big picture

The plastic industry is making floods worse two-fold: through pollution and its staggering greenhouse gases. It makes sense then that flood management solutions adopt a systemic approach to the problem.

Right now, two proposed bills exist in the Senate, both of which aim to tackle the plastic crisis through taxation. The goal is to deter consumers from buying single-use plastics by raising prices.

Recently, the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority suggested waste incineration as another possible solution—a proposal that Climate Reality Philippines vehemently opposes. Incineration is a counterproductive approach to plastic waste management. Providing a seemingly easy solution, this proposal may inadvertently incentivize increased plastic production.

In terms of addressing the issue of pollution and flood control, these proposals are not enough. The plastic problem is deeply rooted in overproduction and consumption, far surpassing the realm of individual responsibility.

The real solution now lies in connecting the dots and retracing the lines. To solve the country’s plastic issue, policymakers need to step back and look at the big picture—determine the root cause of the crisis and start there.

Beyond holding consumers accountable, officials should get huge plastic-producing companies to take responsibility. And more than promoting proper waste disposal, authorities should implement bolder moves to combat the impacts of plastics on our environment, with a focus on eliminating single-use plastics.

About the author: Red Carao has worked in the communications field for more than five years. Starting out as a writer for local and foreign digital agencies, she eventually developed an interest in public relations and development work. In her first stint as a public relations officer, she had the opportunity to work with institutions such as the United Nations, the International Labour Organization, and the European Union. She earned her bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of the Philippines Diliman in 2018. She is currently a Communications Officer at The Climate Reality Project Philippines.