One morning, I felt like having a pandesal that could bring me back to my childhood—warm, chewy, and kind of sweet.

Sadly, our modern-day grocery and fancy chic supermarket bakery don’t make pandesal that would bring back remembrances of things past. I sometimes get treated by a batch of traditional freshly baked pandesal from Laguna by former Dulaang UP artistic director and now Cultural Center of the Philippines technical advisor for artistic matters Alexander Cortez, but sadly nowadays finding authentic pandesal isn’t as easy as it used to be.

So, to give in to my cravings, I made sure to limit the probability of disappointment by going to the oldest bakery in Manila, just 22 minutes from my home, Panaderia Dimas-Alang, established in 1919. Their pandesal did not disappoint! It truly hit the spot. It would have been better with tsokolate eh, which isn’t the same as tsokalate ah, the latter being thin and watery while the former, of better quality, is thick and creamy.

When I was little, we would sometimes have pandesal served with tsokolate eh. My dad taught me to slather butter on my pandesal and dip pieces of it into the hot chocolate. Yummy!

Pasig City Museum now stands as a place that showcases the rich history of Pasig City.

Formerly known as Panaderia Dos Hermanos, Panaderia Dimas-Alang is located along A. Mabini Street in Pasig. It was owned by a certain Alejandro Gonzalez. When his wife died, Gonzales passed on the business in 1919 to his late wife’s sister, Teresa Raymundo Santos. The bakery is now managed by Teresa’s grandson, Manolo Lozada, who has kept with tradition by continuing to bake traditional Filipino pastries and some new ones as well.

Jose Rizal used Dimasalang as a nom de guerre while writing for La Solaridad, a newspaper created by Filipino liberals based in Spain on Dec. 13, 1888. Another name he used was Laong Laang.

was once used as a meeting place for Katipuneros and was often used as an escape route

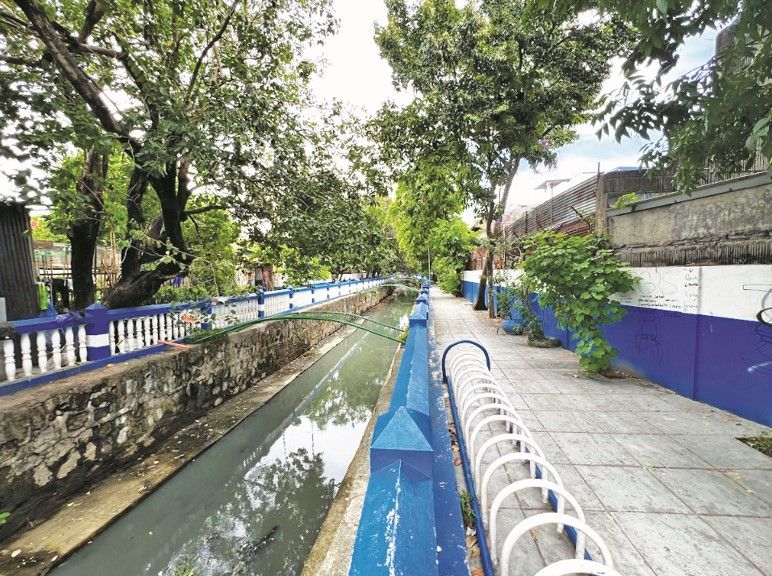

I admit, I am not a person with high EQ (emotional quotient). I would be one of those children who would eat the donut despite being told I would be given more if I just waited a few minutes. Maybe call it age, but I held back this time. I stopped myself from eating my Panaderia Dimas-Alang pandesal by convincing myself the pandesal would taste even better after running Pasig City’s 3.4-kilometer “Bitukang Manok Linear Park, which was not far away. The linear park, which follows the Bitukang Manok Creek, also known as Parian Creek, is one of the city’s historic sites. The park goes through several barangays and one can’t miss it because of its blue and white railings and the paved pathways on either side.

At times when whiffs of malodorous smells coming from the creek reach me, I am taken back to some countries I’ve been to countries, especially located along deltas. Venice immediately comes to mind. I would tell myself, “Parang Venice lang!” The smell on certain parts of the creek will definitely take you back and yet this seems to dissipate on a windy day like the day of my run or when passing along pocket gardens, forests, or woods. The pathways on either side are lined with trees that provide shade and the sound of their leaves rustling in the wind serves as white noise in the background, making the walk or jog even more relaxing. Don’t forget this is a neighborhood. There are residents sitting by the creek, watching the world go by. There are children on school break playing with marbles and even with mud, sticks, and leaves picked from their surroundings. Gates lead to small alleys while doors open up to homes that give a glimpse of Pasiguenos’ lives.

The Bitukang Manok has stories to tell. Pasig was founded by the Spanish colonizers on July 2, 1573. The Spanish built the local government and church by the Bitukang Manok, which they later named “Rio de Pasig.” Interestingly enough, while Intramuros has had its fair share of conflict with the Parian located outside its walls, Pasig also had its “Parancillo” or Little Parian. The Parian was a structure built adjacent to Intramuros to house Chinese merchants during the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines. The Parancillo was its Pasig equivalent, located opposite the Administration office, along a portion of the Bitukang Manok. Today that stretch is known as the Parancillo or Parian River.

Bitukang Manok served to make Pasig a burgeoning economy during Spanish colonial times. According to Dr. Lusicano P.R. Santiago in his article “The Saga of kang Manok”, Bitukang Manok not only allowed merchandise and trade to flow between Pasig and Manila as well as surrounding areas, but it also served to feed Pasiguenos by way of “irrigating rice plains, the Cababan (“lower parts”) behind the town proper. These fields yielded an early harvest of rice called ‘paaga’ in November to feed the people of Pasig and surrounding places, including Manila, while they waited for the regular harvest in January.” Paaga is described as “a kind of quick-growing, early-season rice.” Dr. Santiago also theorized that Pasig boomed since its geographic location became the meeting point of the Bitukang Manok and Bambang Rivers, which “created a golden opportunity for local merchants to act as middlemen in a booming captive market.” One such merchant was Don Cecilio Tech y Cabrera, the owner of the oldest Bahay na Tisa in Pasig.

The Bahay na Tisa in Pasig was built by Doña Fabiana Siangco in 1850. When she died, her daughter Dona Saturnina Cruz inherited it. Saturnina was married to Cecilio Tech y Cabrera, whose wealth was derived from the trade of betel nut. Chewing betel or nganga was a popular pastime by both locals and our Spanish colonizers.

I have chewed both the betel nut and betel leaves. As an archaeologist specializing in prehistoric earthenware pots, I have encountered betel nut lime containers. Even today, in the market of Pasacao in Camarines Sur, where I first encountered the betel leaves, it is being sold by old ladies with weather-beaten skin. Not long ago, Blackbird restaurant would serve an appetizer wrapped in the betel leaf. Traditionally, the leaf is used “as a stimulant, an antiseptic, and even breath freshener.”

It is said that the betel nut leaf should be chewed with slaked lime or with the areca nut. On an archaeological reconnaissance mission in the mountains of Agusan del Norte, a Manobo family offered me the areca nut, the seed of the areca or betel palm. On our way back from a potential archeological site, a family of Manobos was ending their day of harvesting abaca fiber by chewing clumps of betel nuts along the dirt trail. The family offered our team some nuts. After seeing me struggle to bite into the fibrous nut, the head Manobo bit one open for me to chew. The team sat and chewed with the family and not long after we thanked them for their hospitality, explaining that we needed to go and go fast to beat the setting sun with still a few kilometers to go before reaching base camp. Let’s just say, however, that the team barely made it with just a sliver of sunlight left for the life of me. I still have no recollection of the trail journey back to base camp.