Financing a just and sustainable world

By Keith Sigfred Ancheta

In 2009, during the 15th Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP15), developed countries announced an ambitious climate finance goal—that developed countries would mobilize $100 billion annually by 2020 to developing countries to help them implement climate measures that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase their adaptive capacities to climate impacts.

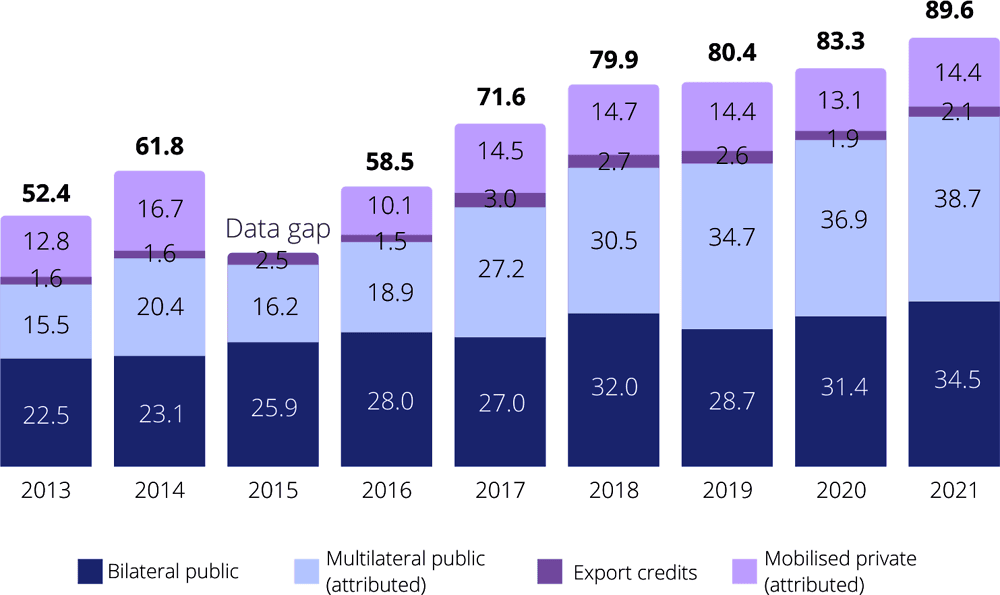

Almost 15 years have passed since COP15, but developed countries have consistently failed to reach that $100 billion goal. According to a report by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, climate funds from various sources for developing countries amounted to around $89.6 billion. Even if this figure is the highest over the past four years, it still falls short of the actual goal that developed countries set.

However, if we look at the bigger picture, we’ll realize that the financial gap is even wider than just around $10 billion. Based on the climate targets that countries have submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), developing countries would need an estimated amount of $2 trillion to implement these targets.

The said gap is highlighted in the first Global Stocktake adopted in COP28. If the world wants to transform communities towards climate resilience and ensure that the world stays below 1.5 degrees Celsius, there is a need to rethink the way the finance flows.

The COP29, which is scheduled in November 2024 in Baku, Azerbaijan, is expected to be a finance-centered climate change conference. As decided in Dubai during COP28, countries who are parties to the Paris Agreement should agree on a common framework for mobilizing climate finance—the New Collective Quantified Goal. It will supersede the $100 billion goal, ensuring the allocation of climate finance is based on the needs, priorities, and strategies of developing countries that will be accessing those funds.

Creating a framework that lays out how much money is needed and where the money would go is one thing. Finding where the money would come from and directing financial flow toward climate and sustainability measures is another. Developed countries are notorious for announcing empty promises—saying that they will provide financial support to developing countries but doing otherwise. That is why the different funds under the UNFCCC have limited budgets.

It’s like having different bank accounts, but all of those bank accounts have little to no money. Aside from the limited budget, the inaccessibility of these funds adds a burden to developing countries that desperately need financial assistance to implement climate adaptation and mitigation measures.

If we are to abide by the principles of climate justice, developing countries shouldn’t beg for financial assistance that they will use in climate action. Instead, developed countries must pay for the damages they have done to the climate, environment, and people. Data shows that only a few countries have emitted the majority of the anthropogenic carbon emissions that have accelerated climate change. These countries are directly responsible for all the impacts that the climate crisis has brought to vulnerable countries.

The said reason is why it shouldn’t be an argument that developed countries must provide adequate financing for developing countries to build their adaptive capacity to the climate crisis and transition to a low-carbon economy. In addition, these countries must also pay reparations for the irreversible loss and damage that climate-vulnerable communities have experienced over the years.

As countries set to submit their updated Nationally Determined Contributions and National Adaptation Plans, the finance provisions stated in Article 2.C and elaborated in Article 9 of the Paris Agreement should be operationalized through the adoption of the New Collective Quantified Goal. Developing countries need to have a clearer idea of how they will implement their conditional targets.

In the upcoming 60th Meeting of the Subsidiary Bodies in Bonn this June 2024 and COP29 in Baku this November, our calls for adequate, equitable, and accessible climate finance must be louder. We must hold developed countries accountable for their commitments and the actions they have taken, and more so for their inaction.

About the author: Keith Sigfred Ancheta is a climate advocate, communicator, and stubborn optimist. By volunteering for different organizations, he has led projects on creative communication, capacity development, policy engagement, and youth empowerment. He has also written pieces about topics related to climate change and young people and has conducted research on One Health. He is currently working as the Technical Associate of Parabukas, Pte., Ltd., and as the Climate Finance Program Officer of The Climate Reality Project Philippines.