WALA LANG

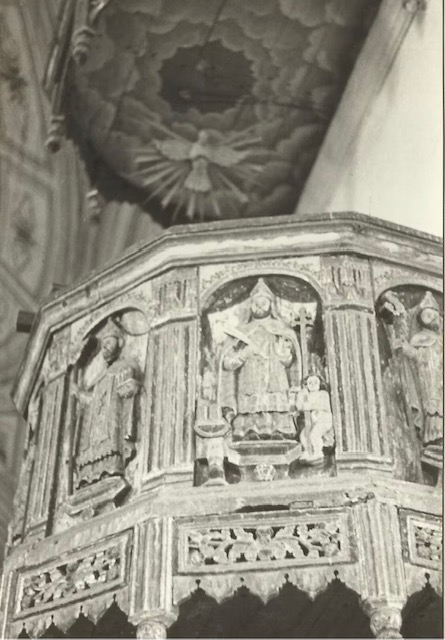

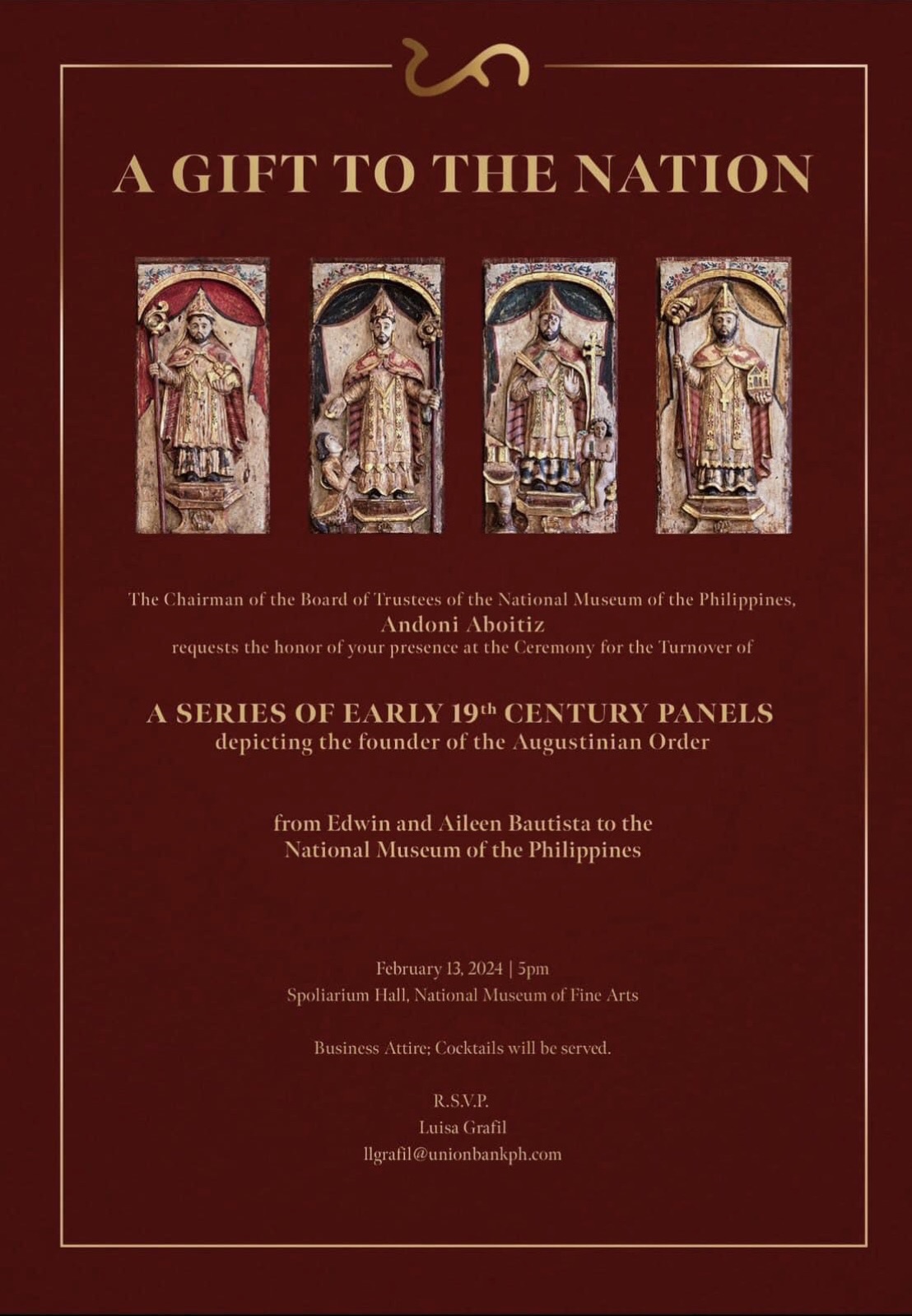

It was a high-profile affair at the National Museum, “A Gift to the Nation,” when Edwin and Aileen Bautista turned over to chairman Andoni Aboitiz and director-general Jeremy Barns a quartet of superb relieves depicting San Agustin de Hippo, a theologian and philosopher who lived in the fifth century. They are among the six panels once on the pulpit of the Patrocinio de Maria Santissima Church in Boljoon, Cebu, which dates back to the early 1800s.

The controversy

It turns out that the panels disappeared some time after 1985, either stolen by outsiders or, as rumor has it, sold by then parish priest who had no authority to do so. Cebu Archbishop Jose S. Palma is demanding the return of the panels to Boljoon, saying that Canon Law requires priests to obtain permission from their bishop before disposing of any church-owned objects, that no permission had been granted by the then Archbishop Ricardo Cardinal Vidal for the sale of the subject relieves, and that in any case sacred objects should not be sold. It seems that the irregular sales, however, were widely known but that these had been going on even before the pulpit panels disappeared. Published accounts relate that Boljoon parishioners had boycotted their own church and heard Mass in the nearby town of Caceres in protest.

Cebu Governor Gwendolyn Garcia and the Provincial Board as well as Boljoon Mayor Joie Derama and the Municipal Council joined the archbishop in calling for the return of the objects to Boljoon, adding that the National Museum itself declared the church as a National Cultural Treasure in 2001 and that the National Historical Institute declared it a National Historical Landmark in 1999. The same church is also reportedly being considered for nomination as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The National Museum maintains that the relieves had been legitimately acquired but that it is willing to dialogue with church and civil authorities.

The care of church treasures

Boljoon church had magnificent retablos, santos, images, and other objects accumulated over the three centuries of its existence. In the church proper were impressive retablos; silver objects galore—alter frontals, candlesticks, altar tablets, sanctuary lamps; images of Augustinian saints, some with ivory heads and hands. In the sacristy and convent were gold-plated monstrances, chalices, and ciboria; vestments embroidered, and other valuables. In the late 1980s, word in Ermita antique shops was that various objects being openly sold were from Boljoon.

If memory serves, I was offered (but did not buy) vestments embroidered in gold thread, supposedly from there and shown photographs of a large painting still in its retablo and of the same retablo already bare.

Other churches are similarly bereft. I visited Bohol’s Baclayon Church in the late 1970s and was shown into a locked convent room with shelves and chests filled with carefully guarded objects. I asked to check the room when I visited about 10 years ago and there was hardly anything in it.

A large room above Loboc church’s sacristy had what was in effect a giant metal cage with boxes and cases filled with accumulated valuables. It was rarely inspected but when it was, it was discovered empty. Persons unknown had cut a hole on top and hauled everything out.

Antipolo church had 17th-century relieves depicting the history of the sacred image. Some survived World War II, one of which is now in Forbes Park. Until the church’s latest renovation, Quiapo’s Black Nazarene was under a wood baldacchino. Its posts now grace the lanai of a provincial home. Three large 18th-century relieves from an unnamed Bicol church are in Quezon City and Ayala Alabang.

Silver objects said to be from Majayjay, Laguna were for sale in the 1980s. Among the items available in a Makati shop were ceriales and the six poles used to hold the cloth canopy over the officiating ecclesiastic during processions. I happened to visit Majayjay at about that time and saw how part of the proceeds were supposedly being used. Azulejos tiles probably of the 18th century were being pried off the sanctuary and replaced by beige marble tiles often used in CRs. There was a pile of the discarded and broken azulejos tiles outside and I got me the largest piece as a souvenir.

Moving forward

Much has gone but it is still not too late for church authorities to revive the old practice of having a formal inventory (with professional photographs and dimensions this time) of valuable church objects and having a formal turnover when parish priests change. Monitored by the bishop or archbishop, this will establish accountability and with luck safeguard parish heritage.

Proving that an object was stolen is tough without photographs and a record in the police blotter. Assuming that there is proof, I am told that there is no statute of limitations applicable to stolen objects. In other words, the original owner can recover a stolen object from a later holder without paying compensation. The unfortunate later owner is supposed to recover what he paid from the one who sold it to him, and so on back to the thief. It won’t be easy.

Considering how many church objects are now in museums and private collections here and abroad, it seems in order for the hierarchy to take the matter up and decide on what to do. This won’t be a simple task, considering that a policy would have to cover eventualities like disposals with or without proper authority; disposals to raise funds for church repairs, conservation, or restoration; disposals for church modernization or “improvements” like porte cochères; disposals by casino-going priests. Then there are objects that may have come from Bicol or Panay or Bohol but from precisely what church is unknown.

The Civil Code has provisions relevant to the Boljoon panels. Article 1505 provides, “Subject to the provisions of this Title, where goods are sold by a person who is not the owner thereof, and who does not sell them under authority or with the consent of the owner, the buyer acquires no better title in the goods than the seller had, unless the owner of the goods is by his conduct precluded from denying the seller’s authority to sell.”

Then follows a long list of complicated ifs and buts that would take the Courts a long time to decide on, as to where the “Gift to the Nation” should rest: Manila, Boljoon, or somewhere else.

Note: Many thanks to Mario T. Zinampan for pointing out the relevant Civil Code provisions. Zinampan is a lawyer and assistant secretary at the Department of Overseas Filipino Workers.

Comments are cordially invited, addressed to [email protected].