The uphill jeepney ride to the coffee-growing town (1,700 meters above sea level), on rocky, dusty and unpaved roads could be daunting. The panorama of a mountain range partly veiled by clouds, with sun rays slicing through, is indeed a sight to behold. But Atok's terrain is harsh and unforgiving to clueless newcomers and holiday tourists.

"Hindi madaling puntahan ang lugar namin. Baka mahulog kayo sa bangin (It’s not easy to go there, you might fall off the ravine," Kalsada Company Country Director Tere Domine said.

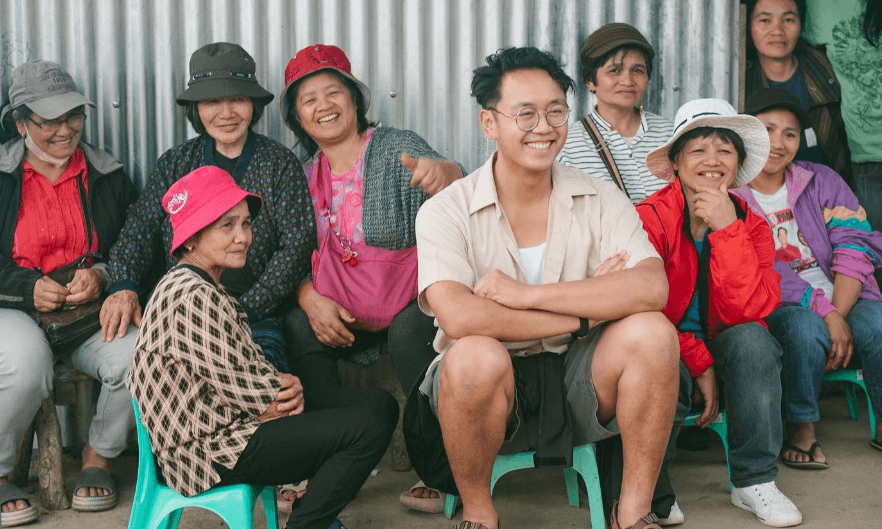

Barreto, who co-founded the Out of Office Roasters in Long Beach, California, with several colleagues had a clear purpose for visiting Kalsada's specialty coffee farms in Atok, Benguet, in 2023. They wanted to know how the farmers grew their coffee beans and how they lived. And like many Filipino-Americans who grew up in the US, Barreto was curious about the Philippines.

Barreto's film narrative is straightforward and devoid of dramatic tricks. It captures the daily hum of the coffee-growing life of residents in the mountain town: moments of intense hard work in silence, stretching for hours, and of farmers patiently waiting for the harvest or the next stage in the post-harvest process.

In one scene, a young woman seated on a low stool puts coffee cherries into a grinding machine from which comes the pulp and juice. Then, there are shots of coffee-drying beds in the sun. Like the shy townsfolk, the film shows more than it tells. Dialogue in the film are snatches of conversation that Barreto was able to record. Usually, Kalsada founder Carmel Laurino, another Filipino-American in search of her cultural roots, and Domine, Kalsada co-founder and community organizer, speak for the farm folks.

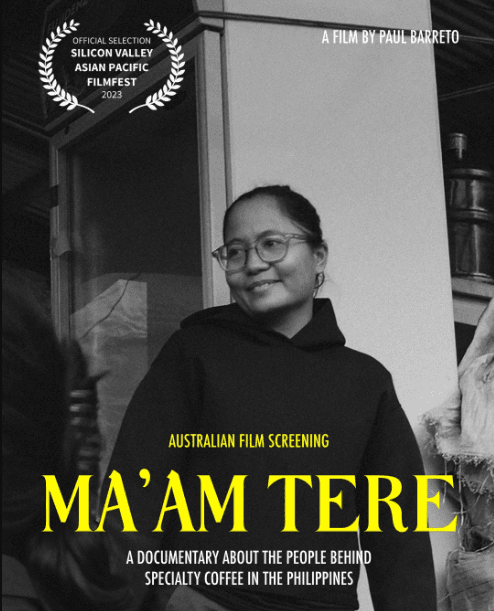

Domine is closest to the farmers as she has become their advocate in dealing with coffee buyers, in seeking help during times of money troubles and virtually, their supervisor (although Kalsada has designated farm managers.)

The Kalsada website describes Domine as a coffee professional, a trained and licensed Q grader. A coffee website defines a licensed Q grader as somebody who can "evaluate and judge the quality of coffees ... on multiple levels," according to the standards and practices recognized and set "by combined coffee associations in Europe and North America" like the Coffee Quality Institute (CQI) and the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) in 2017.

"A lot of coffee here are just backyard... They use the coffee (trees) as their fence," Domine said in one of the film's scenes. For residents of Atok, Benguet, coffee growing is a way of life and holds a deeper meaning in their rites and traditions. When their children marry and build their own homes, they plant the seeds that grow into coffee trees, in their backyards. These coffee trees symbolize the growth of their own families.

In the film, Laurino and Domine said that in the Atok farms, they used the washed processing method to prepare their coffee greens. Washed processing is similar to natural processing, but organic matter is stripped off of the coffee bean within days of the coffee cherry being plucked from the tree and then washed with water before they are dried. This removes any impurities and gives the coffee a cleaner taste, it was explained.

Coffee growing has become just as important for Atok families in the past 10 years after the arrival of the Kalsada Company with its pioneering goal of creating Philippine specialty coffee and selling roasted beans and later, just the greens to mainstream markets, here and abroad.

It was not that way before the Kalsada era when farmers did not know that their talents and skills could produce world-class coffee. Before and even now, residents would still grow other high value crops like vegetables as sources of alternative income in some parts of the year because it takes a lot to venture into coffee, according to Domine who spoke in a Q & A session after the film showing at The Curator Coffee and Cocktails Bar in Makati City on Sept. 29.

In the film, Domine said Kalsada had acquired coffee plantations totaling 11 hectares in Atok. These were sold to the company by farmers who have stayed on as Kalsada's plantation employees who work during the planting, harvesting and post-harvest stages.

Kalsada's farm workers are now being paid more than the minimum wage, according to Domine. Farmers' roasted coffee beans and later just the greens, are being sold at premium prices or higher than the average farmgate prices in the market, she said.

Barreto's film allowed a rush of emotions towards the end when Auntie Asthrine Pias, the recognized community leader of coffee farmers in Sitio Belis, Atok, spoke at a gathering held to celebrate the visit of Barreto's group in 2023. Auntie Asthrine is also recognized by Kalsada as a top producer of their best beans. In the scene, she candidly said: "Salamat sa Kalsada. Sana bilhin nyo pa ng mahal ang kape naming. Mahirap, mahirap ang trabaho ng kape. Baka sabihin nyo, 'Ang sarap nito.' Pero ang tutoo, ang sarap ng trabaho (Thank you, Kalsada. We hope that you will continue to buy our coffee at high prices. It is hard, hard work to grow coffee. You may say, 'This is delicious.' But the hardwork is delicious, too),” she said.

“We hope that God will grow your business so farmers like us here in the mountain will benefit too. We hope that your businesses get more support and hopefully, people will look for our Arabica coffee here in Sitio Belis, Municipality of Atok, Benguet,” she said in Filipino.

Operates like a social enterprise

It's par for the course: The more a unique enterprise succeeds, the more challenges it will face. When the Kalsada Company started growing coffee greens and roasting beans, in Atok, Benguet, in 2015, they were not expecting that from about a ton of produce, they would be supplying coffee chains, here and abroad, 11 tons and even 15 tons in a few years. Big business was not necessarily what the founders of Kalsada had in mind at the start.

Take it from founder Laurino, a Filipino-American who grew up in Seattle. When she founded Kalsada in 2014, she had just been inspired by a historical photograph of Filipino Barako coffee being sold in Pike Place Market in 1909. It piqued her curiosity about her cultural roots and sparked her desire to reconnect with the Philippines. She saw a way to do it by founding a coffee beans supply business for specialty coffee shops together with Lacy Audry and Domine. Atok's coffee growers drew the interest of the three women upon learning their coffee-growing activities had something to do with family traditions.

"Actually, in the beginning, the plan was to just export coffee to the States. Our founder, Carmel Laurino, is from Seattle. She came upon the 1909 photograph of Filipino coffee being sold in Pike Place Market. That was literally the inspiration for Kalsada. So the intention was to bring (Filipino) coffee back to the States. But then again, when we tried to do that, it was not easy. We had to go through bureaucratic processes. So we ended up retailing in the Philippines so we can sell the coffee sitting in the warehouses while we're waiting for the permits. That's when we started roasting a little bit and serving our coffee here and in cafes in other parts of the Philippines.

“During the pandemic, we stopped roasting because we assessed where we're good at and where we could be more of use. Many of the cafes in Manila now are also roasting their coffee so we'd rather supply greens to them so we can focus on the production side. So since 2022, we've been planting a lot of coffee in Bukidnon and in Benguet, and also supporting other enterprises with similar goals," Domine said.

Kalsada is a business that actually works more like a social enterprise. Domine, who took care of organizing the farming communities that joined Kalsada in growing coffee in Sitio Belis, wanted the business to profit and flourish. But from the start, she knew Kalsada had to take care of the farmers in the form of above-average prices for their produce.