A rich boat-making tradition

Tracing the Philippines' maritime roots

At A Glance

- Another sea vessel indicative of the existence of a strong and developed maritime tradition in the Philippines even before the point of contact with our colonizers is the balanghai.

In my previous article, I talked about the Austronesian Migration Expansion and how maritime technology increased our ability to sail longer and farther. The Austronesian-speaking people settled in and around China about 6,000 years ago, then about 3,500 years ago, groups started to migrate to the Philippines (as a jump off point), then to other islands in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. This maritime culture came with a rich boat-making tradition, even observed by colonizers upon the point of contact, as documented in Maximilianus Transylvanus’s book De Moluccis Insulis, a compilation of accounts by survivors of the Magellan-Elcano expedition (1519-1522), Italian scholar and member of the expedition Antonio Pigafetta’s journals, now known as A Report on the First Voyage Around the World, among others.

Not long ago, I was introduced to the many modes of watercrafts found in the Philippines by Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Division senior museum researcher and officer-in-charge Bobby Cuaton Orinllaneda. You see, I was reading old correspondence of my great-grandfather Daniel Arcilla Romualdez to his relatives regarding booking safe passage back to Leyte for his three sons Norberto, Miguel, and Vicente Orestes, who were stranded in Manila during the siege of Andres Bonifacio on Intramuros in 1896.

Norberto, Miguel, and Vicente Orestes were studying at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila and, as the school shut down because of the siege, found themselves stuck in Manila. It took a few months before the boys were able to book a passage to Negros and then, finally, to Leyte. Bobby pointed me to the article “Types of Watercrafts in the Philippines” by Ricardo E. Galang, where he enumerated and described the different types of watercrafts that had been used in the archipelago since the point of contact with Spain.

Based on the article, my lolo (Vicente Orestes) and his brothers would have taken a schooner to get back home.

On one of my proxy duty trips for my cousin Senator Imee Romualdez Marcos, I was sent to Negros. At the event I was attending, I told a Negrense about how my lolo and his brothers had to flee Manila during the siege of Manila. I asked him why it was necessary to book a boat bound for Negros instead of going straight to Leyte. He explained that in the middle of the 19th century Negros saw a period of rapid economic expansion on account of the widespread cultivation of sugar. There was a lot of traffic of trade goods and, because of the booming economy, many were migrating to the island. Negros had a bustling port with a lot of vessels coming in and out from all parts of the archipelago. Just to note, two years after my lolo and his brothers boarded their boat to Leyte, Generals Aniceto Lacson and General Juan Araneta joined Aguinaldo’s revolutionary army and laid a successful siege on the Spanish garrison in Negros.

Another watercraft mentioned by Galang was the karacoa, the largest locally made vessel at the time made for war and raiding. They were owned by chieftains and when decked up could carry as many as 300 warriors. Spanish accounts would describe the sight of at least 50 or so karacoas at a time attacking settlements along the coasts of Leyte and Samar and at times going head on with Spanish fleets. What a sight that would have been!

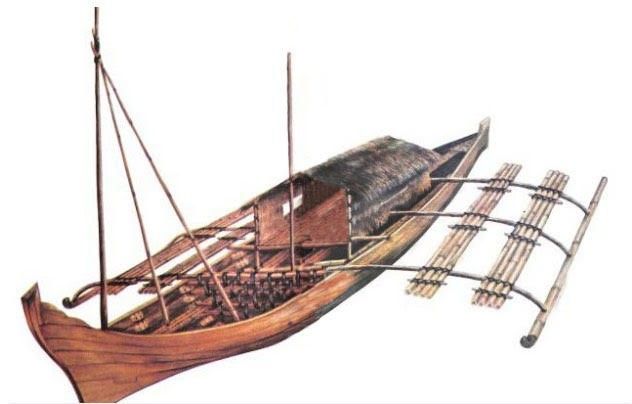

Another sea vessel indicative of the existence of a strong and developed maritime tradition in the Philippines even before the point of contact with our colonizers is the balanghai, described as “beyond 30 meters long, with squared keels and edge-pegged planks.” The balanghay or balanghai is also where we get the word barangay from.

Today the barangay is known as the smallest political unit or “administrative division” in the Philippines. As it was when the barangay was first observed by Spanish colonizers to be “well-organized independent villages serving under a chief,” the barangay today is the “primary planning and implementing unit of government policies, plans, programs, projects, and activities in the community.” Also, it exercises judicial powers to settle disputes between and among neighbors. In simple terms, the barangay is tasked to address the immediate concerns of members of its community and cater to their wellbeing.

The late President Ferdinand E. Marcos (PFEM) believed that the barangay system could restore power to the people, “where it properly belongs.” PFEM believed that the barangay provided the humble citizen who could not be heard and who seemed powerless with a ready access to political authority through his barangay. This political authority is the barangay captain, who is accountable to his constituents on “a daily basis and (is) the people’s link to government,” he explained.

Voter’s registration in the Philippines ended on Sept. 30, 2024 and the filing for Certificates of Candidacy has now begun (Oct. 1 to 8, 2024). Participatory democracy is still in its infancy in the Philippines whose independence has been regained only in 1946, only to be succeeded by a number of republics (five total in nearly 100 years!). We are still learning but as Plato in The Republic is quoted as saying, “The beginning is the most important part of the work.”