At A Glance

- 'Dear Ninoy, I am constrained to write to you another note because of the claims you made in your television interview last night… It is also quite obvious that you not only rendered service to a foreign government, which could be classified under the nature of espionage, that you actually went out of your way to offer intelligence information to that foreign government.'

I was four years old when Martial Law was declared in the republic. I remember being brought to Malacañan compound with my family to stay with my dad’s older spinster aunt and cousins at what was then known as the tea house or at least that was what we called it then.

We weren’t allowed to go out and, as kids during the age without internet, we were left to our own devices to entertain ourselves. I remember one time we were given a treat by being allowed to venture further out into the palace grounds and saw a tank. We had a blast clambering on and around it.

Thinking about it now, I hope our childish antics gave the soldier manning it in full military armed gear a brief respite from the tense situation we were all in at the time, although tense for me was being away from home and somehow knowing something was up and aware the grownups were keeping something from us. That something was the uncertainty of what would come next after the declaration of Martial Law in the country.

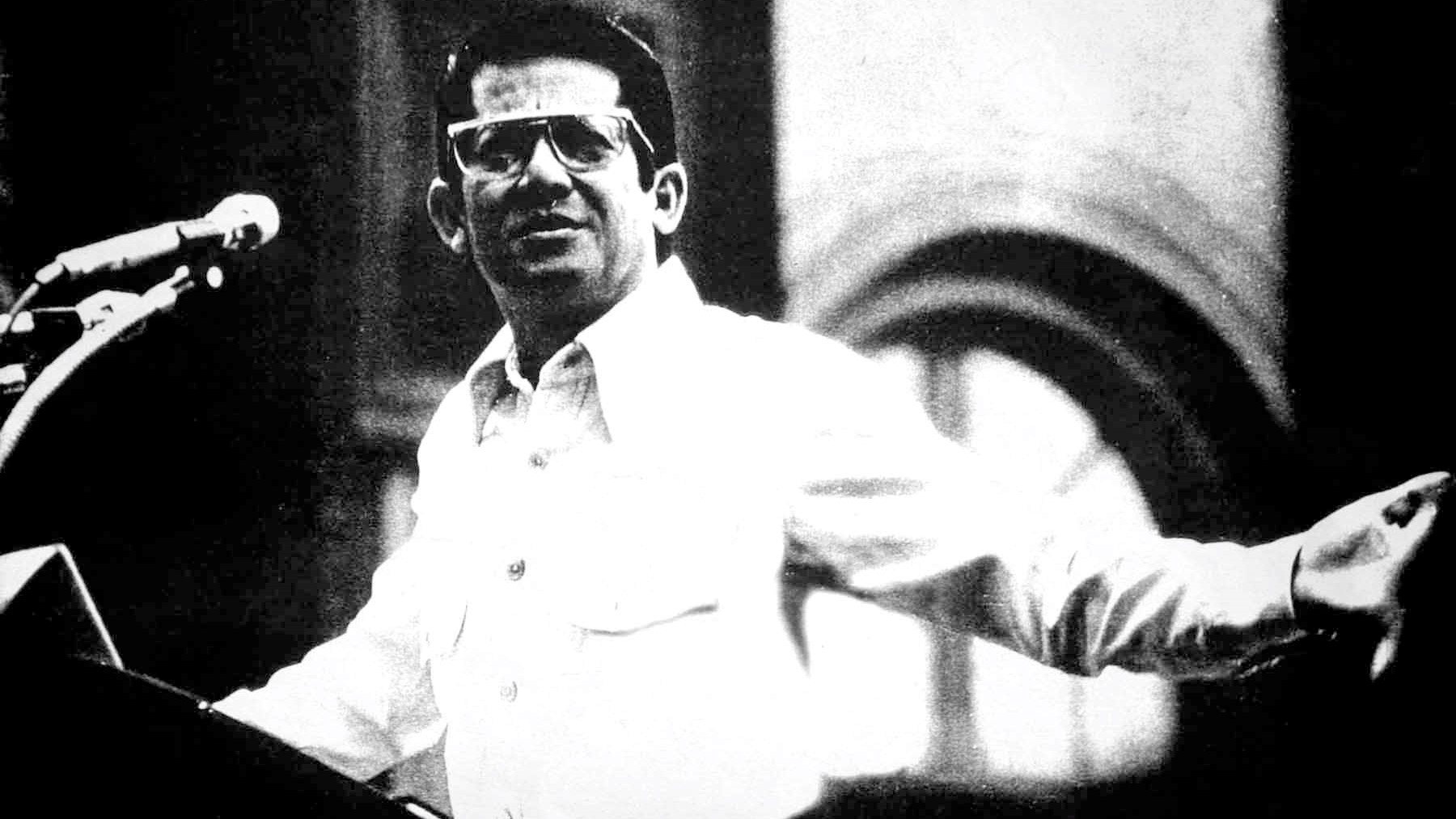

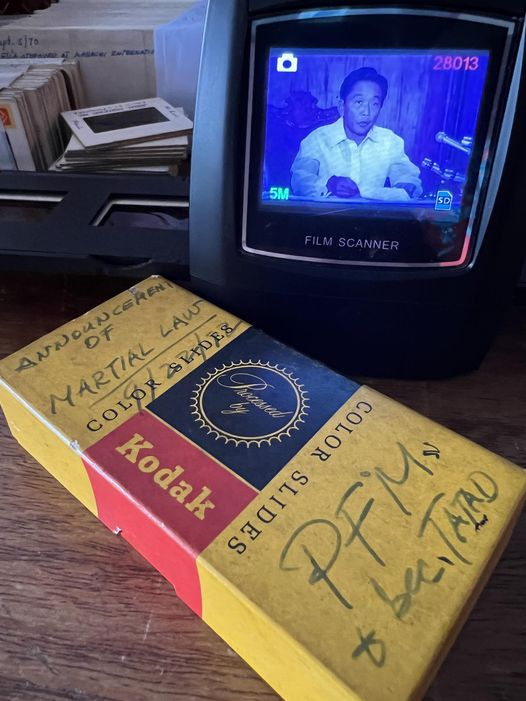

President Ferdinand E. Marcos (PFEM) declared Martial Law on a Saturday, Sept. 21, 1972. I never really took time to look deeper into this event in Philippine history. In fact, most of what I learned was gleaned from what was being said on foreign media and annual memorials printed or broadcast by various Filipino media institutions, so the perception I had was based on the view point of PFEM’s critics until I started doing archival work in PFEM’s old home.

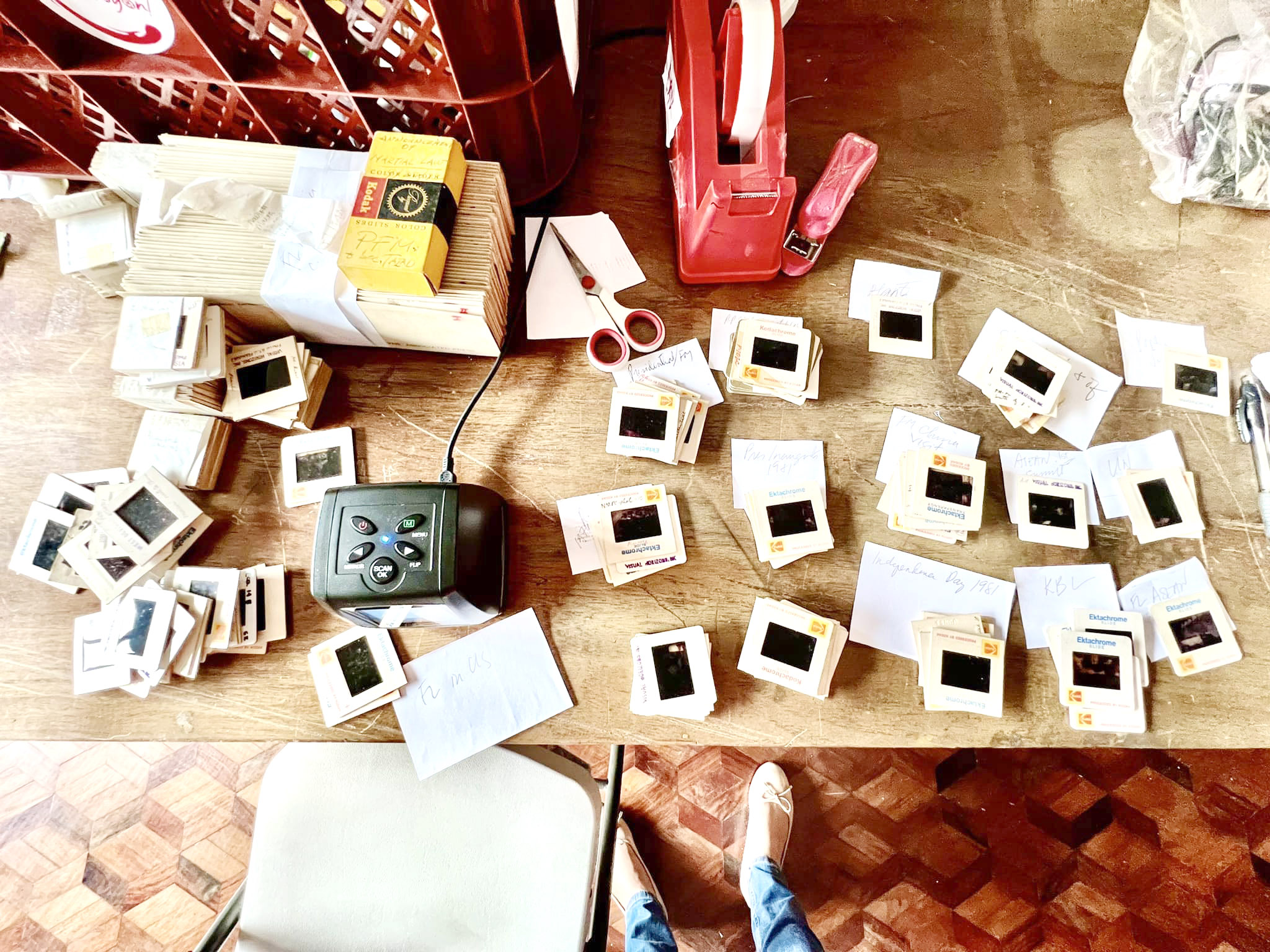

Who would have imagined one could pick up so much just by going through personal items and written materials like books and diaries? Often, I would message my mentor archaeologist and professor at the University of the Philippines School of Archaeology Dr. Victor Paz. We would end up discussing events that took place during PFEM’s time. Paz was a street parliamentarian and a staunch activist against the Marcos administration in the early 1980s.

I would give my take on issues of those times based on my chance readings of books and other personal documents of PFEM on the matter. Paz would then caution that PFEM was convinced what he was thinking was true so, “It is important to find supporting historical evidence for each conclusion that he had at that time.” My response to him was that I have had 37 years’ worth, since 1986, of people saying all these things that happened during PFEM’s time, most of it from his detractors. That was the foundation of my knowledge of historical events in the ’70s up until the Edsa Revolution of 1986. The literature I am being exposed to now was written in real time and a first-hand account of what transpired and comparing what I know with this “added knowledge” has compelled me to do a major recalibration.

One major recalibration on my end was to erase any notion Ninoy Aquino was a victim. He was an equal player in the game. He was fully cognizant of what he was doing to further his political ambitions. He used his wealth, connections, and power to attain his goals. It was expected that he would bid for the presidency in 1972 and PFEM extending his stay in power would thwart this plan. I mention Ninoy only because it was one of a few names I recognized and would see it mentioned in documents in the weeks, if not months, leading up to the declaration of Martial Law. Based on PFEM’s diary and Juan Ponce Enrile’s accounts, I began to wonder, “Was Ninoy actually in league with the communists?” On Sept. 19, 1972, PFEM wrote, “Released the Report of Secretary (Juan) Ponce Enrile of Sept. 8, 1972 where he reported that Sen. Aquino had met Jose Maria Sison of the Communist Party and had talked about a link-up of the Liberal Party and the Communist Party.”

This was of deep concern for PFEM because he knew if Ninoy became president, the nation would fall into communist hands. Was the son now also going to be accused of treachery? I was involved in a book project on the history of the Philippines and I learned that Ninoy’s father Benigno Aquino Sr. was flown to safety by the Japanese from the Philippines to Japan when American forces were making their move to liberate the Philippines. Aquino Sr. was arrested and imprisoned in Yokohama prison when American forces occupied Japan and then flown back to the Philippines to be tried for treason. He was eventually acquitted. Aquino Sr. was accused of being a collaborator with the Japanese during World War II. Some would also say the name Aquino and treachery would come up again in the case of the deletion of the country’s claim to Sabah in the 1987 Constitution under Ninoy’s wife Cory Aquino’s administration.

But to me, Ninoy was also the young man that my Auntie Meldy, Imelda, would occasionally talk about when asked. You see, when Imelda finished university, she left Tacloban, Leyte for Manila to work. In Manila, she stayed with her first cousin, then House Speaker Daniel Zialcita Romualdez (1907-1965), and his wife Paz “Pacing” Gueco of Magalang, Pampanga. Paz was a first cousin of Ninoy’s father Aquino Sr. Imelda and Ninoy knew each other well since Ninoy was tasked sometimes to take Imelda out for lunch when she was working in Escolta by his aunt, Imelda’s cousin-in-law Paz. It took a double take or two to get used to all these things I’ve been unearthing from history’s archives.

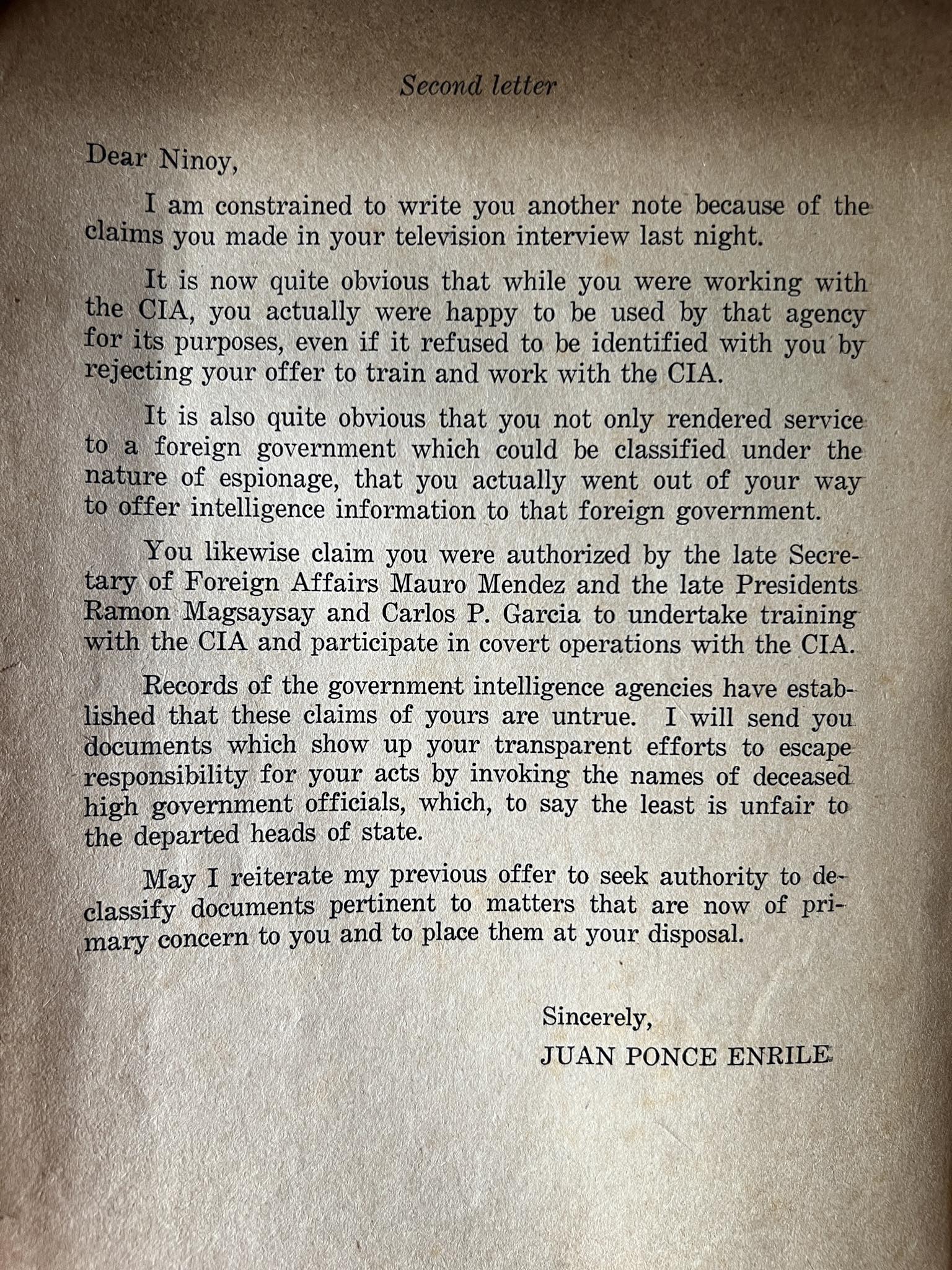

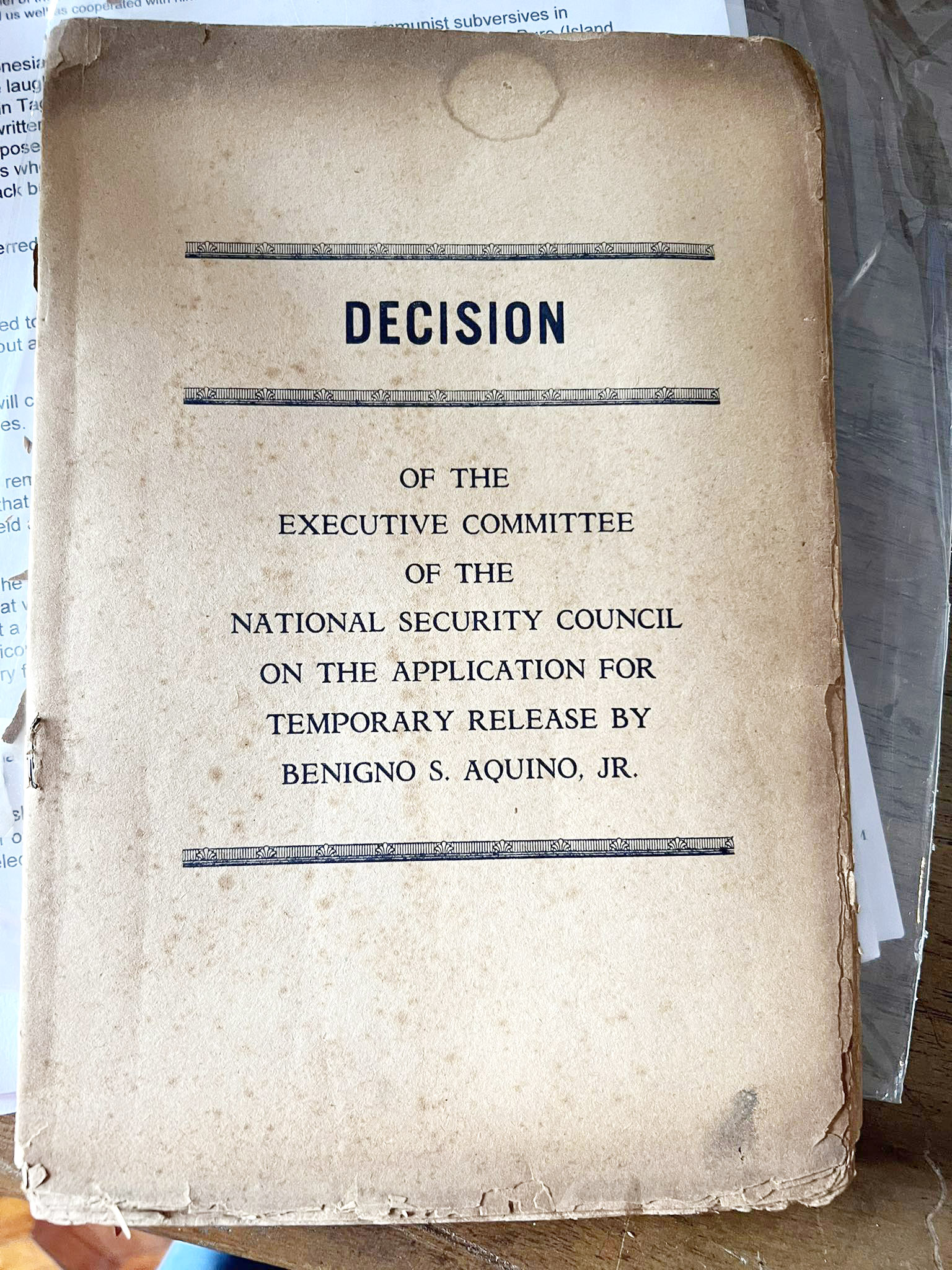

For instance, I read in a report, “Decision of the Executive Committee of the National Security Council on the Application for Temporary Release by Benigno S. Aquino Jr.” (so he could run in the 1978 Batasang Pambansa Election) Ninoy appeared on television claiming to be a CIA agent and had forwarded government intelligence. Upon hearing this Juan Ponce Enrile confronted Aquino, having confirmed first with the CIA if Aquino Jr. was indeed a CIA operative (which the CIA denied, confirming, however, that Ninoy did in fact offer to give intelligence to the agency).

In a very strong letter, Enrile wrote: “Dear Ninoy, I am constrained to write to you another note because of the claims you made in your television interview last night… It is also quite obvious that you not only rendered service to a foreign government, which could be classified under the nature of espionage, that you actually went out of your way to offer intelligence information to that foreign government.”

Sensing perhaps that, with all the information not known by the general public or information that have been forgotten or purposefully hidden, I was turning into a keeper of things that should remain in the dark, I asked counsel from Dr. Paz, “Paz, have I completely gone to the dark side?” He assured me, “No you have not, just deep into the world of your current research, which is how it should be.” “But I’m not doing research. I’m doing archival work and unconsciously absorbing things whether I want to or not,” I clarified. Paz explained, “A good archivist is doing research. Look at you, reflecting already on the materials you are organizing.” And by coincidence, of late, I am coming across materials from the Martial Law years in our country’s history.

The 51st anniversary of Martial Law was held a few days ago and what I have learned was that my uncle took full responsibility for this action. “Great decisions are made for us as much as we make them. I am, to be sure, accountable to history for 21 September 1972 when I signed the proclamation placing the entire Philippines under Martial Law. And yet solely and completely responsible as I am for this decision, I cannot escape the sense that events, the thrust of history, and even the will of the people somehow guided my hand to the deed. I say this not to exculpate myself in advance—this is impossible, no man can cheat history—but offer one more instance, out of personal experience of a well-known suspicion: that behind every man who makes history are forces which blur the distinction between individual initiative and historical necessity. The adherents of opposing views of history can find whatever support that may please them, but to the man who, like myself, has touched by a single act the very nerve of history, it is a source of confidence to know that while he stands alone, he had not acted in isolation, outside or in opposition to the compelling circumstances of his time and place.”