Coastal erosion causing land to vanish in Kalayaan Islands, UP-MSI study reveals

While rising sea levels have placed Manila among the world’s “sinking cities,” new research from the University of the Philippines-Marine Science Institute’s (UP-MSI) Geological Oceanography Laboratory revealed that coastal erosion is also a significant problem.

Led by marine and coastal geology expert Dr. Fernando Siringan, the study under the Resource Inventory, Valuation and Policy in Ecosystem Services under Threat: The Case of the West Philippine Sea (RE-INVEST WPS) project focuses on the beaches of the West Philippine Sea.

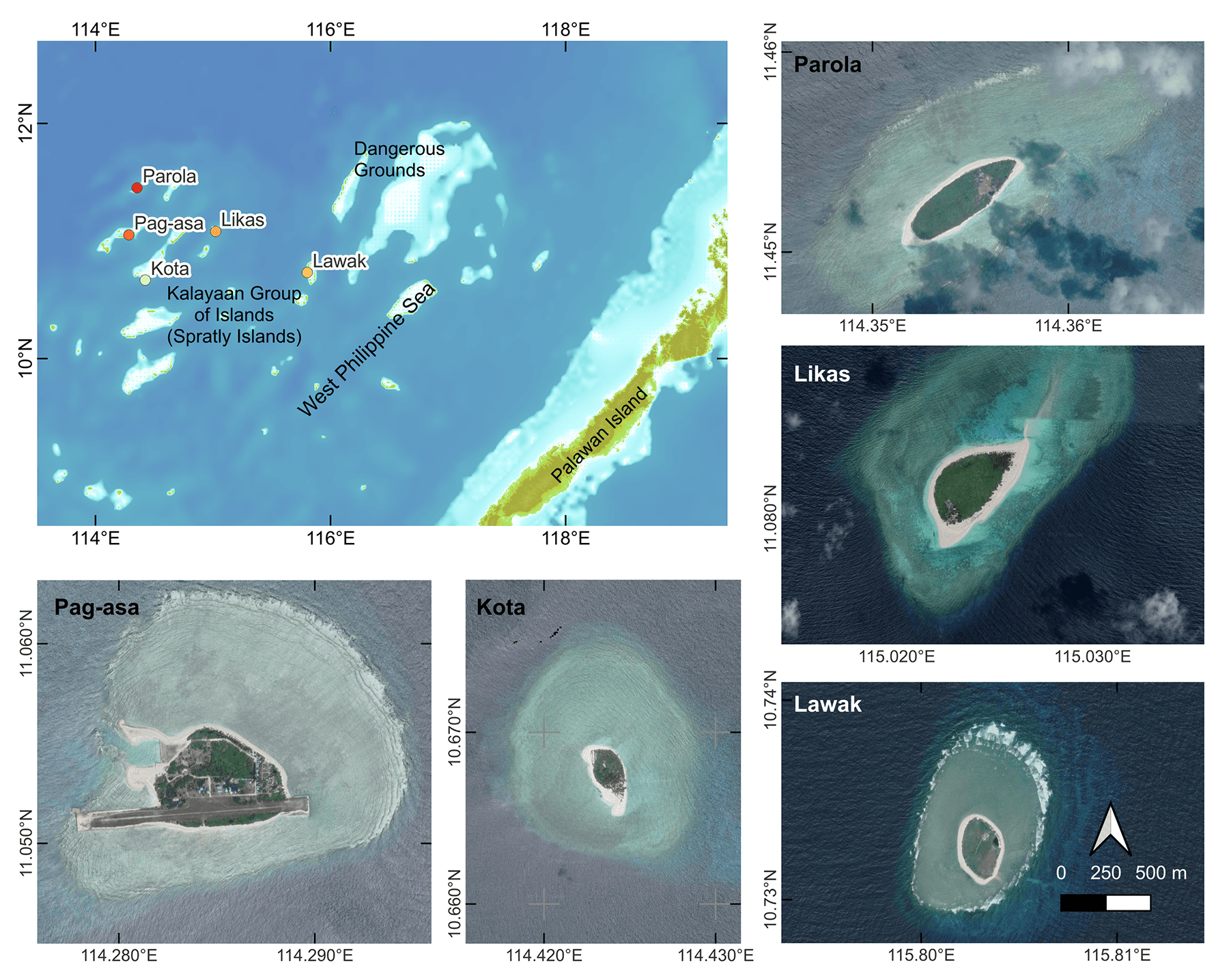

Collaborating with the Socio-Economics Research Division of the Department of Science and Technology-Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic, and Natural Resources Research and Development (DOST-PCAARRD), Siringan and his team have used satellite imagery and field surveys to map coastal erosion on the islands of Lawak, Likas, Kota, Pag-asa, and Parola since 2005.

Man-made impacts

“Overall, coastal erosion is dominating,” said Siringan, who has studied coastal erosion in the Philippines for over 30 years, in a UP-MSI article.

UP-MSI explained that coastal erosion occurs naturally when sediment loss exceeds the sediment supply due to currents, runoff, and winds.

This process can be exacerbated by man-made structures like piers and groins, which block coastal currents, causing sediment to accumulate on one side while depleting the other and accelerating erosion.

Mapping erosion

UP-MSI’s study revealed that over the past two decades, Pag-asa has been losing 1,500 m² of land per year, making it the most eroded island among those studied.

Project researcher Anne Drew Carillo attributes this erosion to “solid-based” man-made structures extending from the coastline.

Other islands experienced less severe erosion, with Lawak losing 440 m² annually, Likas losing 740 m², and Kota losing 410 m².

UP-MSI noted that for these “very small” islands, these figures represent a “massive” loss.

In addition to sea-level rise caused by global warming, offshore reef islands are gradually submerged due to their subsiding nature as atolls.

In contrast, Parola has gained land, which Siringan explained is a result of destructive human activities that unintentionally released sand from the reef flat.

UP-MSI pointed out that while this land gain may appear beneficial, the impact of human activities on local biodiversity cannot be overlooked.

It said the destruction of coral reefs has displaced fish, invertebrates, and other marine life from their natural habitats, negatively affecting fisheries in the area.

Moreover, the land gained from the released sand is only a temporary gain.

The loss of corals makes Parola increasingly vulnerable to future coastal erosion.

“If the area of human activity-damaged sites off Parola is not reoccupied by corals, then a shift to a more erosional state will take place,” project researcher Jeffrey Munar explained.

The study highlighted that in the Philippines, many beaches are formed by currents bringing in sediments from coral reef-dwelling organisms such as corals, calcified algae, mollusks, crustaceans, echinoderms, and the single-celled protists Foraminifera.

Coastal erosion on coral reef beaches is naturally mitigated when these sediments flow in to replace the eroded material.

“It is our thriving biodiversity that sustains the iconic white sands of Boracay, Palawan, and other popular tourist destinations. A healthy reef also protects the coast, as corals can weaken strong waves before they reach the shore. Weaker waves means less force that would erode the coast,” the researchers said.

Conservation challenges

Siringan’s key takeaway from the Kalayaan Island Group studies is that coastal erosion can be mitigated as long as sediments continue to be replenished.

“Kailangan mabawi [ang coast] (We need to recover the coast),” said Siringan.

“We need to improve the health of coral reefs para ang wave protection at sediment source functions nila ay maibalik (so that their wave protection and sediment source functions can be restored),” he added.

Siringan’s research aims to identify sustainable methods to preserve island integrity.

Given the rapid rate of sea-level rise in the Philippines, he said it is crucial to address and slow land loss due to coastal erosion.

“Ma-target lang natin [ang pag-maintain ng islands], okay na (If we can just target maintaining the islands, that will be sufficient),” said Siringan.

“Pero syempre, mas maigi na lumaki siya. ‘Yan ang kwento ng coastal erosion sa West Philippine Sea (But of course, it would be better if it grows. That’s the story of coastal erosion in the West Philippine Sea,” he added.