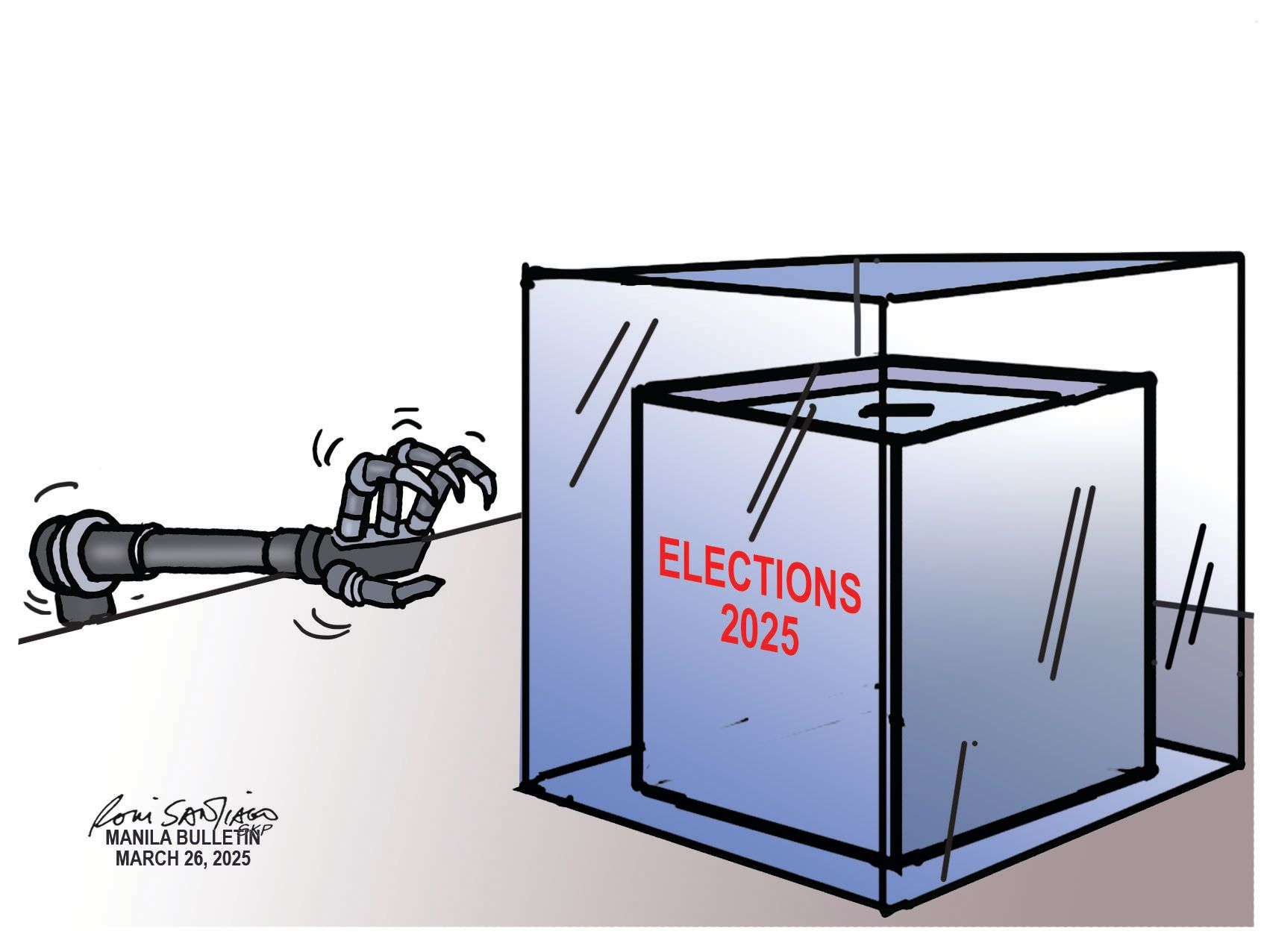

“Dagdag-bawas” scheme—the practice of vote-padding and shaving to manipulate election outcomes—is impossible in an automated election system.

Commission on Elections (Comelec) Chairman George Erwin Garcia confidently declared this on Monday, March 24, 2025, in a chance interview with the media.

For a nation that has been haunted by allegations of vote manipulation each time an election is held, the declaration is a welcome development.

At a glance, this assertion aims to reassure the public of the integrity of the country’s electoral process. But a closer examination is crucial: Is the automated election system truly foolproof, or are there still vulnerabilities lurking beneath the surface?

The country first implemented nationwide automated elections in 2010, aiming to modernize the process and reduce human error, inefficiency, and most importantly, the opportunities for manipulation. With technology at the helm, it promises a quicker, more transparent, and tamper-resistant voting process.

The Comelec chief’s declaration on the impossibility of “dagdag-bawas” in an automated environment is grounded in the notion that once votes are cast, they are digitally recorded, making it difficult, if not impossible, to alter results. True, automation has streamlined many facets of the electoral process. However, to dismiss the possibility of manipulation entirely is perhaps overly optimistic.

The primary assumption behind Garcia’s claim is that the machines used in the election process—such as the Automated Counting Machines—are tamper-proof. While they are designed to prevent tampering, they are not impervious. For instance, if malicious actors were able to compromise the election system before the votes are cast or even manipulate the software that runs the machines, the entire process could be compromised. Moreover, the integrity of the system is also tied to the physical security of the voting machines, storage of ballots, and the transmission of results. Any weakness in these areas could still open the door for vote manipulation.

When examining the effectiveness of automated elections, it’s essential to look at the experiences of other countries. For example, nations like Estonia and Brazil have successfully implemented electronic voting systems that are widely regarded as secure and transparent. Estonia, often praised as a leader in digital democracy, has introduced e-voting, where citizens can cast their ballots securely online. The country has invested heavily in cybersecurity and the Estonian model includes multiple layers of checks and balances, including encryption and a paper trail for each vote, providing an additional layer of security should there be any doubt about the results.

Brazil, another pioneer in electronic voting, uses a system that has withstood years of scrutiny. The Brazilian Electoral Court (TSE) introduced electronic voting machines in the 1990s, and while the system has had its critics, Brazil’s implementation stands as one of the most successful in the world. What sets Brazil apart is its emphasis on transparency. Election audits, the publication of raw data, and citizen observation of the process have made the system relatively resistant to fraud.

However, even the most advanced systems are not without risks. In 2020, researchers identified vulnerabilities in some automated voting systems used in the United States. These findings underscore the importance of constant vigilance and regular system audits to ensure the electoral process’ integrity.

The key takeaway is that while automation offers significant improvements over manual elections, it is far from foolproof. Automation, without comprehensive safeguards, can create a false sense of security.

For the Philippines to achieve a truly foolproof automated election system, it must look beyond the machines themselves. It must invest in continuous monitoring, independent audits, public transparency, and ensure that all stakeholders—from political parties to ordinary citizens—can have confidence in the system.