A culture of disaster

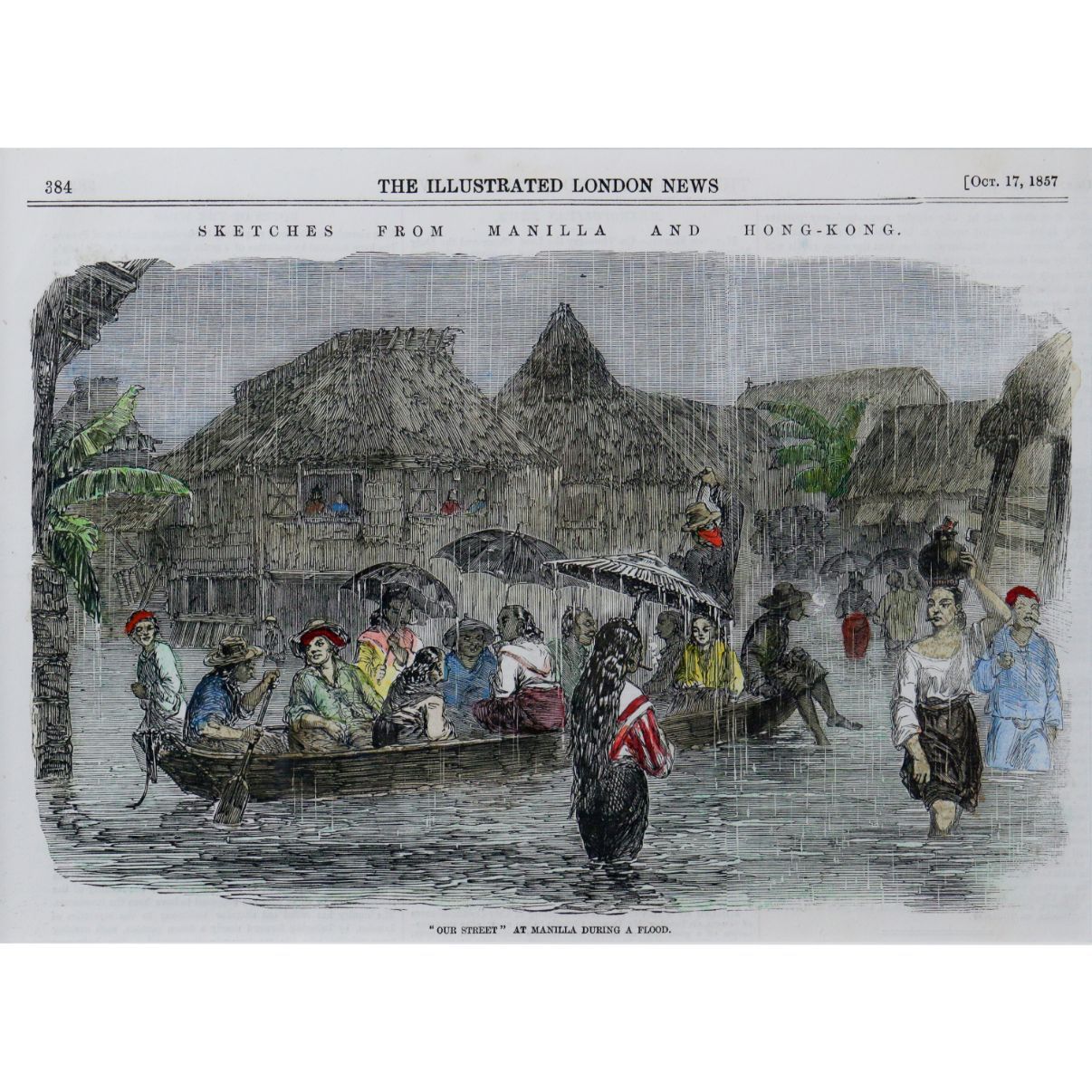

Has the tragedy of devastating floods in stormy weather become a way of life among us Filipinos?

At A Glance

- The DPWH 2024 budget for flood control projects is ₱225 billion. Its flood control budget was ₱90 billion in 2020, ₱101 billion in 2021, and ₱182 billion in 2023.

The Philippines has established a culture of disaster, “a societal or organizational mindset that develops in response to frequent or severe disasters, whether natural or human-made.”

It is characterized by well-established protocols and responses drawn from the concrete experiences of communities. Of late we have been struck by a number of disasters as a result of typhoons that have brought strong winds and flooding in the metropolis, the latest being Typhoon Enteng.

The Filipino’s response to flooding has been very fluid. You see the trauma of losing loved ones and property and yet you also see Pinoys taking things the only way they know how—in stride, posting song-and-dance reels on social media platforms like Tiktok to inject levity in dark circumstances. With decades of typhoon disasters and inherited behavioral responses to these disasters, one could almost say it has begun to be a way of life. Even now, the 5,500 flood control projects highlighted by President Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr. during his 2024 SONA cannot possibly contain the deluge that occurs across the archipelago during a typhoon onslaught, especially in densely populated areas like Metro Manila.

My recent brush with evacuation centers in the Marikina and Pasig areas during the previous Typhoon Carina as part of my cousin Senator Imee Romualdez Marcos’ NutriJeep feeding program, showed me how evacuation had become well entrenched in a community’s culture of disaster. Often public and private school buildings, sports arenas, and even malls, as we saw during Typhoon Carina, are converted into evacuation centers. The old ways of seeking refuge on rooftops (although many still resort to doing so) are now being replaced by coordinated and systematic evacuation practices in times of typhoon and tropical depressions. Behavioral changes in choosing better building materials for houses and incorporating architectural components to ensure structural integrity or even resettling far away from hazardous areas have also been a result of past experience of flooding disasters. As soon as some people leave these hazardous zones, however, others move in, especially those, who have just migrated from the provinces in search of better jobs and a place to reside.

The United Nations has stressed that, though viewed as a commodity, housing is in fact a human right. It is “the basis of stability and security for an individual or family. The center of our social, emotional, and sometimes economic lives. A home is our sanctuary, a place to live in peace, security and dignity.” At last week’s national convention of the Organization of Socialized and Economic Housing Developers Incorporated (OSHDP) at Solaire Resorts North, participants addressed the looming housing crisis in the country.

The UN says housing needs in the Philippines will continue to balloon from 6.5 million in 2022 to 22 million in 2040. Unfortunately, out of the original target of building around six million houses by 2028 under the Pambansang Pabahay para sa Pilipino Program or 4PH, only 1.2 to 3.2 units will be completed, the Department of Human Settlements and Urban Development has announced. Since 2022, there was a backlog of seven million house units and that is not counting the number of housing units needed for the succeeding years. Government records show that, as of 2019, 70 million Filipinos are living in substandard houses. This is projected to grow to 113 million people in 2030. Climate change and other threats posed by disasters are expected to compound the housing problem.

According to the Global Peace Index, the Philippines is the most susceptible country to hazards brought about by climate change. This means that millions of Filipinos, particularly the urban poor who live in informal settlements in areas prone to disasters like flood and landslides, use substandard materials, which make it even riskier in those areas. In an article entitled “Typhoon Ondoy and the Translation of Disaster Expertise in Barangay Banaba, Marikina Valley” by Loh Kah Seng, human activity has exacerbated the problem. “Informal settlers contributed to floods by encroaching upon riverbanks to construct poorly built homes, discarding garbage into the waters, and generally obstructing waterways, said the author. “Urban and eco development like quarrying work have reduced land cover, [and the sheer] number of settlers and increased industrial production have caused rivers to be clogged up by mud, garbage, and debris.” This holds true today in most parts of the metropolis and not just involving informal settlers but the Filipino society as a whole.

Recent flooding in the metropolis have been attributed to rapid urbanization, overwhelmed drainage systems, improper garbage disposal, deforestation of nearby mountain ranges like the Sierra Madre Mountain Range, and climate change.

“A house is made of bricks and beams, a home is made of hopes and dreams,” as it has been said. Such is the value of a home. It will indeed take the government and the private sector working together not only to make accessible and affordable housing for the most vulnerable sectors of society but also ensuring our homes and lives are protected from environmental disasters such as flooding. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction admits that addressing environmental disasters like flooding will involve a multifaceted approach with key elements in disaster prevention and mitigation that include urban planning and infrastructure, environmental conservation, early warning systems, education and awareness, policy and governance, sustainable development, waste management, climate change mitigation, water management, and regular maintenance of flood control structures with periodic dredging of rivers and canals. These key elements should be part of the country’s flood control masterplan.

During the Senate Committee on Public Works hearing probing the massive floods in Metro Manila during Typhoon Carina last month, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) Secretary Manny Bonoan admitted that, despite the massive funding allocated to flood control over the years, “the Philippines has no integrated flood control master plan.” The DPWH 2024 budget for flood control projects is ₱225 billion. Its flood control budget was ₱90 billion in 2020, ₱101 billion in 2021, and ₱182 billion in 2023.

The proposed DPWH for flood control in 2025 is ₱257 billion. But before we talk about next year, where did all those billions meant for flood management go?