Art, healing, and mindfulness

Drawing as therapy with Liv Vinluan at her house on a hill in Antipolo

Imposter Syndrome is described as the state “when you doubt your own skills and successes.”

This was definitely not the case for me, when I found myself in front of an easel participating in a session held by artist Liv Vinluan in a house on a hill along the Sierra Madre mountain range in Antipolo, Rizal, just an hour away from Manila.

I have long since ascertained that drawing and painting are not my medium. Apparently, accepting this has given me an advantage in class. I need not go through the debilitating effect of having too much technical knowledge and artistic choices that could lead to anxiety and difficulty in making decisions on how to execute the first stroke on canvas.

The speed, as well as my seemingly fearless act of composing the elements on my canvas, was noted by Liv. “Ang bilis (so fast)!” she exclaimed.

“It is liberating, not to have a name and a reputation to uphold in the art world. I am unburdened,” I explained.

This is not the case for a lot of her students, Liv revealed, citing how some students would struggle to start. So, she would give them a “prompt.” an idea to get the creative process started. She would do this through collage.

For some, confronting a blank canvas, or a blank page for writers, can be daunting. To make it less so, Liv invites her students to choose pieces from a bin of precut shapes of colored and recycled paper or, if they wish, cut their own shapes. They are then tasked to arrange the shapes on a piece of paper in any way they wish. When done, the pieces of the collage are glued into place to serve as a guide when drawing the pieces in the collage on the canvas. Once the shapes are drawn, the painting can begin. But the process doesn’t end there. Liv enjoins her students to use other mix media techniques. For her it should be a continuous process and, most important, a process of discovery.

What would bother me was uneven lines, lines that are too thick, and uneven brush strokes. I admitted this to Liv, who wasn’t surprised since her place allows this kind of mindfulness. Her sessions often become therapy for her students as well as for her, their teacher.

Art therapy is described as working with art to “explore emotions, understand conflicts or feelings that are causing distress” and to use art in finding “resolutions to those issues.” The art sessions also become moments of sharing. Articulating one’s thoughts and feelings and saying them out loud in a safe space brings relief for some of her students, Liv reveals. Away from the noise and other distractions unavoidable in city life, in a house overlooking the massifs of the Sierra Madre, even the simple things are amplified.

Art has always been a part of Liv’s life. Her father, after all, is Filipino abstractionist and professor emeritus Nestor Olarte Vinluan, former dean of the College of Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines (UP), where Liv graduated with Latin honors.

Liv has won multiple awards, both local and international. Her works have been described as “investigations on death and mortality, the cyclicality of histories, the inconsistencies of human behavior and character, and the passage of time.” She is married to visual artist and UP-Fine Arts professor Ian Juacian. One can say she lives and breathes art. Being exposed to art even before birth has made her realize earlier that colors can affect a person’s psyche.

Liv wants to impart what she has learned to the public. An introvert at heart, she was prodded by her older sister, Lel, also an artist and art teacher, to get out of her shell. Liv is in her element when teaching art, but it also helps when her sister is present during sessions. Lel is the extrovert in this tandem, which has served them and the students who come to this house on a hill seeking peace and knowledge.

Speaking of art, a couple of days after a session with Liv, I found myself admiring the artwork embroidery of some late 19th-century gowns displayed at the Charles Gates Dawes House at the Evanston History Center in Evanston, Chicago. It’s a collection of evening and day gowns and men’s wear belonging to power couple Charles and Caro Dawes in the turn of the 20th century. I stumbled unto this small museum by chance as I was going around in Evanston when I dropped off my youngest son Ian Orestes, who is now there for university.

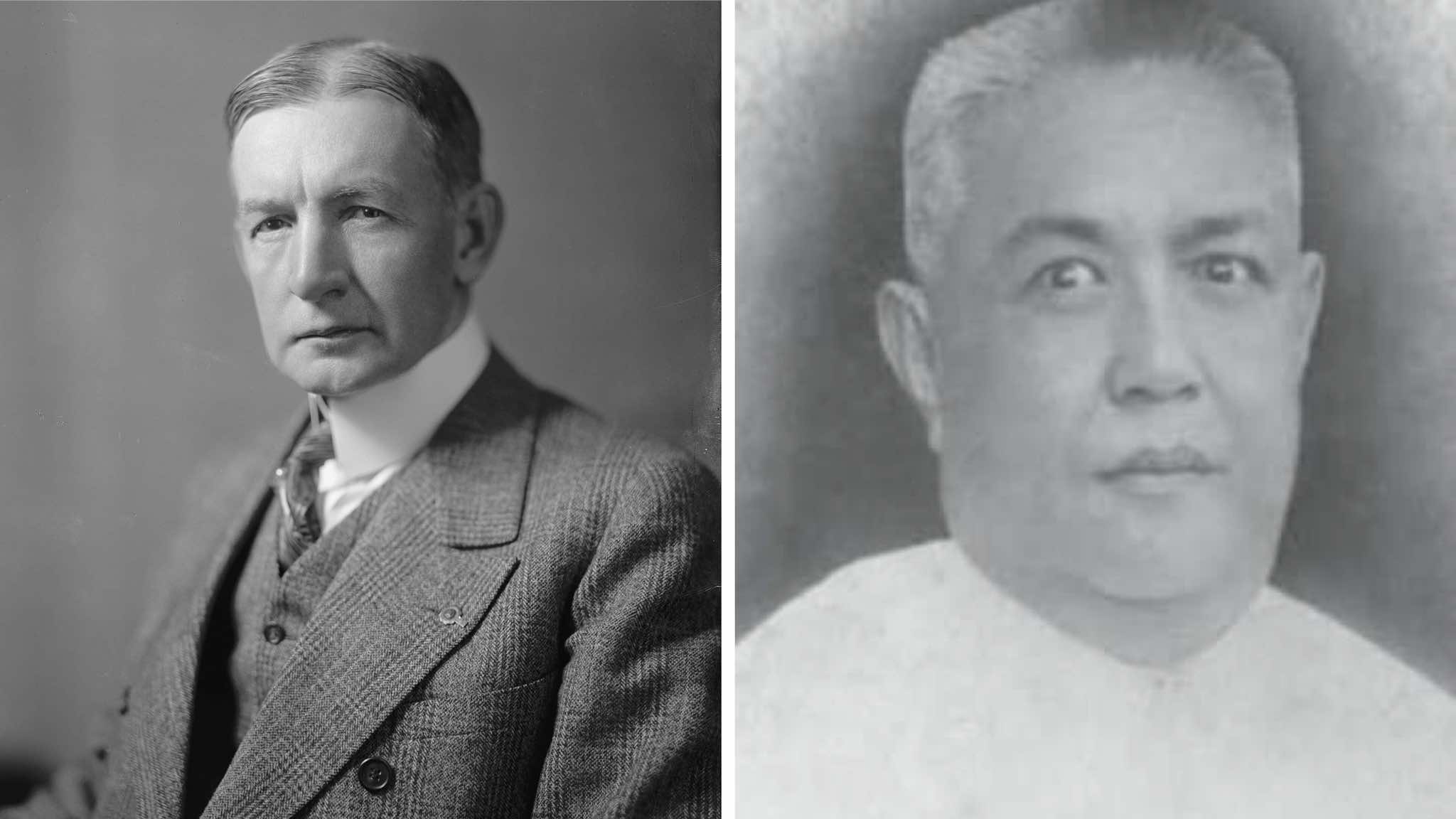

Built in 1894, the Charles Gates Dowes House is in the Chateauesque style, a style popular among the wealthy in late 19th century America. It is a three-story, 14-room house with cathedral-like celings. The name Charles Dowes did ring a bell and even some of the portraits triggered memories. Given the timeline I knew somehow the owners of the house then were related to the Philippines. True enough, after my tour, I referred to my late uncle’s book Tadhana: The History of the Filipino people and found the name Charles Gates Dowes, who was mentioned in the book for his involvement in the Spanish-American War and the conflict in Cuba.

The Spanish-American War (1898) took place during the administration of the 25th US President William McKinley (1897-1901), a war that saw Spain ceding the Philippines to the US as part of the Treaty of Paris in 1898. With the annexation of the Philippines and the resulting Philippine-American War (1899-1902)—because of the resistance of Filipino revolutionaries who were fighting for independence from Spain—America was determined, in the words of McKinley, to “civilize and Christianize” the Philippine population.

Victorious, the American military government proceeded to establish colonial rule over the islands. Just before Mckinley’s assassination in 1901, he had appointed Dowes as a member of the Philippine Commission (1900-1901), headed by William Howard Taft (who was to become the 27th President of the US), and was tasked to establish a civilian government to replace the military regime that had been in place since America took control of the archipelago from Spain in 1898. The Philippine Commission, otherwise known as the Taft Commission, “passed laws to establish civilian government, restructure towns and provincial government, and improve infrastructure.”

The commission traveled all across the Philippines. Among the personal letters of my great grandfather Daniel Arcilla Romualdez was a detailed letter to his wife Trinidad and daughter-in-law Beatriz, giving specific instructions for the decoration and feast in honor of the visiting Taft Commission to Tacloban, Leyte in 1901. Daniel, Trinidad, and Beatrize stood to welcome the members and the family were among the few, who hosted them during their stay. Daniel had served as gobernadorcillo of Tanauan in Leyte during the Spanish colonial period. He was appointed justice of the peace of the province by the revolutionary government of General Emilio Aguinaldo and, in 1901, was appointed by the Taft Commission as justice of the peace of first instance in the Court of Tacloban, Leyte.

I was filled with a sense of wonder and awe at how after more than a century and a few hundred thousand kilometers later, our families would meet again.