Apolinario, a hero for our times

Honoring Mamay Pule, the 'Sublime Paralytic,' on his 160th birthday

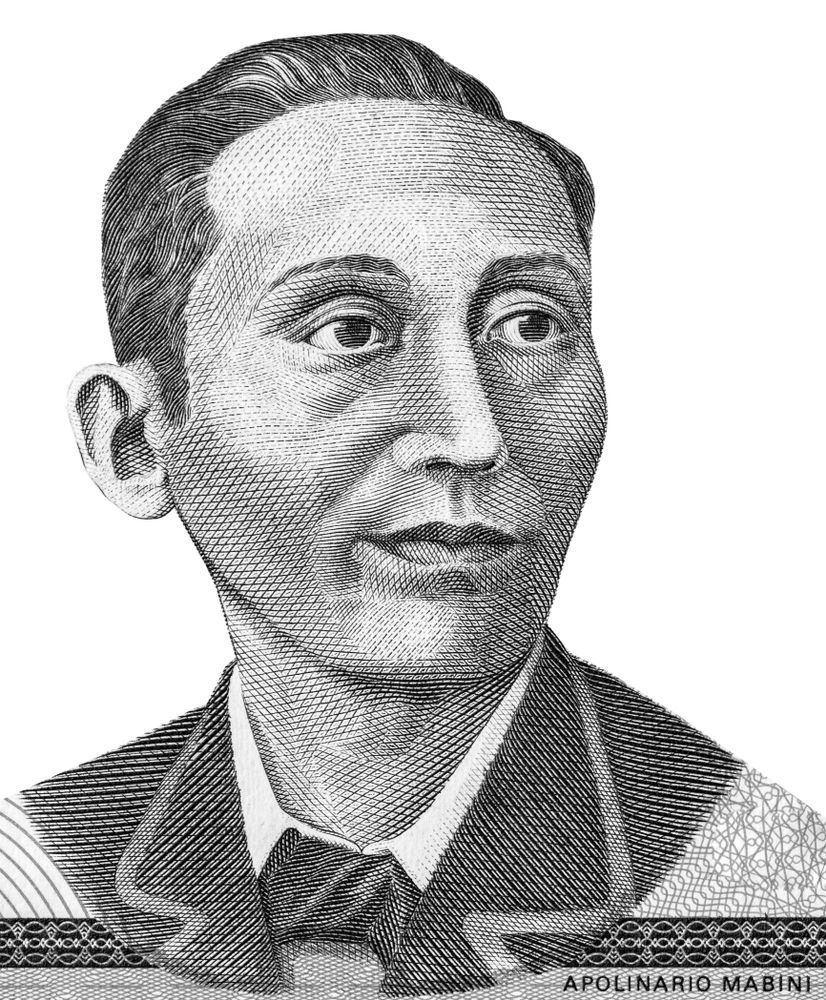

Because Apolinario Mabini’s disability largely defined him, at least in our history books and on those ubiquitous hero postcards of our youth—so iconic was the portrait of a frail man on a chair, struck and weakened by polio—many Filipinos could not be blamed for thinking that the Batangueño hero’s challenges were merely physical. “The brains of the revolution,” he was called.

In the roster of Philippine heroes that included exciting, swashbuckling action figures like Heneral Antonio Luna or Andres Bonifacio, or romantic and dashing sweet-tongued Casanovas like Jose Rizal, Apolinario Mabini seemed, well, boring. He played, in popular culture like movies and books, second fiddle. Supporting character. Sidekick.

Apolinario Mabini may have been considered the brains of the revolution, both against the Spaniards and the Americans; the first Prime Minister of the Philippines; its first foreign secretary, yes—but it seemed, not much else.

He might have formulated the framework of the first Philippine Constitution, wrote books and articles that inflamed the hearts of the revolutionaries and ignited the middle class to rise up, and mapped out strategies alongside President Emilio Aguinaldo, but was his heroism, and the arc of his life, at par with his more popular contemporaries?

The many challenges of a hero

Pigeonholed as a disabled hero, “Mamay Pule,” as he was called by those who respected him (Mamay is lolo, a term of endearment in Batangas, while Pule is his nickname), had a richly layered story that is as—or could even be more so—relevant to the ordinary Filipino than the story of the rich kids of the revolution who had the privilege to be educated abroad.

The only time Apolinario was able to travel out of the country, unlike his contemporaries, was when he was exiled to Guam by the Americans for fighting for Filipino independence, on the heels of fighting for independence from the Spaniards.

His life has been a series of challenges, one after the other.

“Due to poverty, Mamay Pule worked as a servant to several people just so he could finish his studies, as he came from a very poor family,” shares descendant Allan Trinidad Rodriguez, whose paternal grandmother Severina was the daughter of Monico, Apolinario’s sibling.

Having died unmarried and without children at the age of 38 in his homeland, after a bout of cholera he picked up in his exile from Guam, the hero Apolinario nevertheless has many relatives as he was one of eight children to poor, uneducated but hardworking Filipino parents.

His mother wanted him to be a priest, but Mabini always knew he wanted to be a lawyer.

“Not many Filipinos know that nagpa-alila siya (he was like a slave) just so he could earn a little, he was what you would call a ‘muchacho (house boy),’” Allan, whose late father Primo was the family’s representative in national events celebrating the hero, tells Manila Bulletin.

Because of his determination and tenacity, Apolinario Mabini was able to study in Manila, first at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran in 1881, later receiving his law degree in 1894 from the University of Santo Tomas.

“He graduated without having owned a single book, that’s how poor he was,” Allan shares.

Records show that the earnest and passionate young man taught Latin and worked as a copyist in the Court of First Instance in Manila while he studied so he could supplement his income.

Because the image seared into our brains is that of a paralyzed intellectual, many do not know that Mabini only became disabled late into his life, in 1895, when he contracted polio.

Allan shares a family story. “Mamay Pule would walk three days from Tanauan in Batangas to Manila to reach his school, and to stay with a relative in Nagtahan. Even on his graduation day, he just borrowed everything so he could have something to wear.”

Allan continues, “He could have been rich, because he was so brilliant. He would win property disputes for his clients, and they all wanted to give him a part of the land as compensation, but he would turn all of them down, saying he will only ask for what is just and proper.” Allan jests,

“Kaya up to now, most Mabinis are still poor.”

This dignity and pride in his work Mabini carried as he rose to the top, becoming President Aguinaldo’s most trusted consultant.

It was this dogged determination to overcome challenges that carried, literally, the paraplegic even as he became sick and paralyzed. “This was how he was, that even when he became sick, he would perform his duties perfectly in his imperfect body,” Allan adds.

Some of his greatest works Apolinario Mabini would do as an ill man. In 1898 General Emilio Aguinaldo summoned him to serve as his chief adviser. Mabini drafted decrees and crafted the constitution for the First Philippine Republic, including the framework of the revolutionary government which was implemented in Malolos, Bulacan in 1899.

Mabini also wrote one of the country’s greatest literary and political pieces, The True Decalogue (El Verdadero Decalogo), a sort of a moral guidebook on how Filipinos should act and love their country, in 1898.

In his youth, he did not let his overwhelming poverty stop him from achieving his dreams. In his adulthood, Mabini did not let his physical limitations stop him from heading a resistance against two colonial superpowers.

Legacy of a true hero

The family of the Mabinis try to live up to Apolinario’s tenet. Allan says his father has always reminded them to live like their Mamay Pule: “Ang mabuhay at magwagi ng walang panlalamang at panlilinlang (To live and to be a victor without deceit or cheating).”

Asked if they get a degree of superstardom from being related to Mabini, Allan says the locals in Batangas don’t treat the Mabinis differently. “They’re used to meeting and knowing heroes’ relatives,” Allan laughs. “There are the Malvars of Sto. Tomas, and even the Rizals of Calamba, a neighboring city. It’s the tourists who get excited and ask for selfies.”

Allan acknowledges that this kind of fame also has its drawbacks. “The biggest misconception that we hear—and a funny one—is that he acquired his paralysis from a sexually transmitted disease. It is well documented that Mabini got sick from polio in 1895, gradually losing the use of his legs until he became fully paralyzed in 1896.” Later, when his remains were transferred from Nagtahan Shrine to the Mabini Shrine, doctors who did a post mortem analysis found a cyst at the base of his spine that may have caused his paralysis.

Mabini lived with this illness, causing him pain and suffering, and yet, as Allan and his family proudly says, this is the hero’s most precious inheritance to them—“the will to survive under the guidance of justice and integrity.”

Does the family, especially during commemorative events honoring the great Sublime Paralytic, ever get pressured to live up to Mamay Pule?

Allan says, “No, because we’ve accepted that it’s not easy to be extraordinary like him. Mamay Pule was one of a kind.”

(July 23, 2024 is the 160th birth anniversary of Mabini, the hero.)