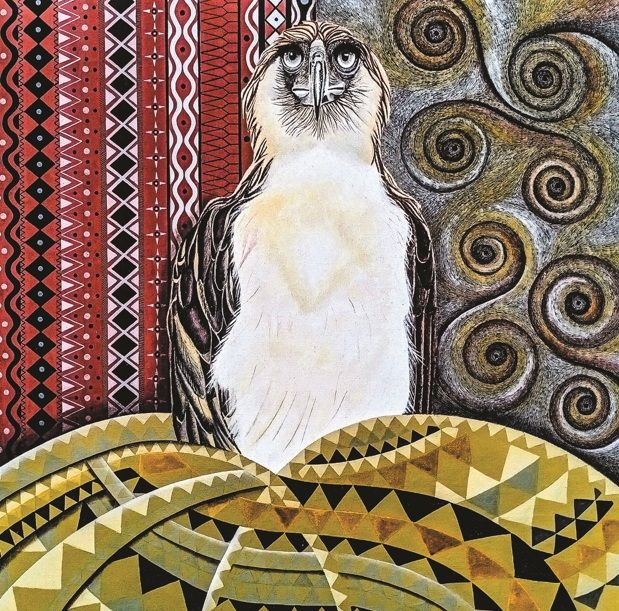

Out of the soil, a thousand things emerge—an eagle glaring with dignity against a backdrop of ornate patterns, eyes growing on a leaf, a giant foot with seven toes.

It is often hard to believe that the paintings of Jhonrey Balane, visual and tattoo artist and musician, are made of soil. With the bliss and tranquillity that often emanates from his paintings, it is even harder to see what a difficult past this 24-year-old artist has emerged from.

Jhonrey is one of the most successful among the Talaandig soil painters, over a dozen artists from the town of Lantapan in Bukidnon who have taken up soil as a primary medium.

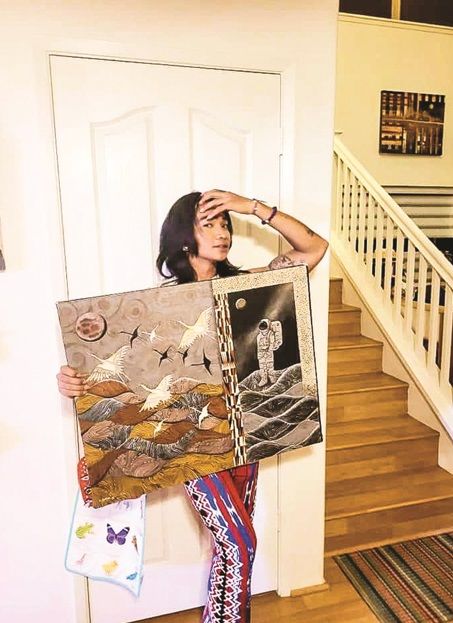

Aside from using soil sourced from different parts of Mindanao, the group is also known for drawing heavily from the vibrant visual traditions of the Talaandig, one of Bukidnon’s seven tribes. The Talaandig soil paintings have been put on show around the world—Jhonrey’s own artworks have been sold in Hawaii, the influencer Bretman Rock being among his buyers.

The soil painting of the Talaandig is often mistaken as an ancient tradition, even in Bukidnon, but it is in fact a contemporary innovation, the brainchild of the Talaandig polymath and cultural custodian Datu Waway Saway. The acclaimed musician and visual artist took inspiration from soil painting scenes from different parts of the world to give his people a cheap way of making art, creating in the process one of Mindanao’s most distinct genres of visual art.

Datu Waway is Jhonrey’s father-in-law. It is from him that he has been learning not only soil painting but also the vast Talaandig knowledge system. From the oral and musical traditions of the tribe to the noble art of fatherhood, Jhonrey is inheriting from Datu Waway many of the legacies that keep Barangay Songco in Lantapan the stronghold of Talaandig culture.

But while his acclaimed father-in-law has given him a tremendous boost, Jhonrey has also managed to slowly carve out a name for himself. He was among the participating artists of the first Daro Art Immersion Program, which the Davao-based organization Lawig Diwa, Inc. has spearheaded this year in partnership with the Metrobank Foundation.

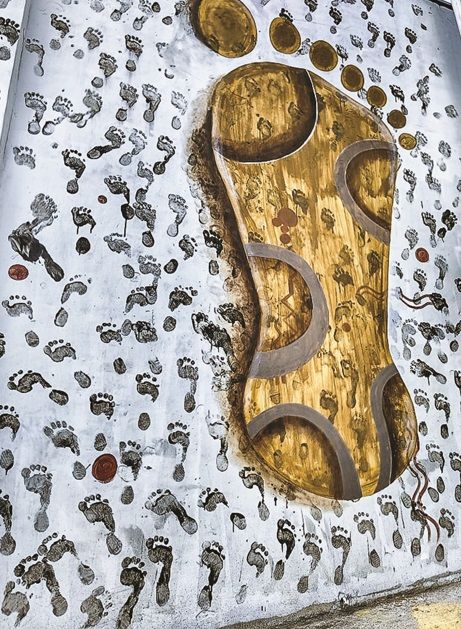

Just after that became the first featured artist of the newly opened Masbad Gallery in Kidapawan City, where he painted what may be the largest soil mural in the country. Kidaputik, the inaugural Masbad mural, may also be the world’s largest footprint mural, as parts of it are covered in Jhonrey’s footprints. In the gallery his painting series, “Saini sa Tagsayaw ha Adagi Banuwa” (visual representations of the rhythm of the city), is the first to greet visitors.

He has gone a long way from a troubled childhood. The instability of his parents meant he had to grow up under the care of his maternal aunt’s family. There were times he returned to the care of his parents in Davao City, where he spent some of his childhood in the squalid slums of Isla Verde.

cousin committed suicide due to bullying for his

ethnicity

The family was so hard up they often had to beg and gather discarded plastic cups in Davao to make a living. At some point, one of his parents even went to jail for getting into illegal drugs.

But Jhonrey recalls this as a formative period in his life. He first became fascinated by art when he saw the works of artist Kublai Millan in Davao’s Peoples Park while begging (today Kublai is one his mentors).

The creative inclination led him to joining a band, a move that was not supported by his family. At some point he had to run away, living with one band mate after another.

It was while making a living as a musician that he met Datu Waway’s daughter Ellahi, who was the manager of their band. In her he would find the stability he had long craved for. Following the traditional Talaandig rites (and after much difficulty winning the trust of her family), he married her. Today they have a son.

His being a husband to Ellahi and father to their son Lawi is a big part of his creative process—Jhonrey is a full time artist. Through his art he has been able to help send Ellahi through college. But more than pursuing art that is able to food on the table, Jhonrey paints and writes music that helps to make a better world. Culture, especially that of the Talaandig, and nature are recurring concerns in his art. These concerns are often in the form of discourse—Jhonrey is one of the most political among the Talaandig soil painters.

The first work of his that caught my eye was IP Discrimination, an eerie and surreal soil painting that was on show during the 2021 iteration of Mindanao Art. It was his way of paying tribute to his cousin Ado, who had killed himself after being discriminated for his ethnicity. It was also Jhonrey’s way of raising awareness of the still ongoing discrimination against indigenous peoples in contemporary Filipino life.

In another later work, Kidagaw, he demonstrates his ability to be very ornamental despite this politics. In the painting he depicts the Philippine Eagle (which calls Bukidnon its natural habitat) with a backdrop of the Talaandig’s geometric patterns. The painting is his attempt to help assert Bukidnon’s iconic claim over the national bird. It is also his way of underlining the importance of harmony between nature and culture.

“Saini sa Tagsayaw ha Adagi Bonuwa” (which literally translates to ‘This Dancing City’), the series on show at the Masbad Gallery, demonstrates his tendency toward abstraction. Although he has a deep understanding of Talaandig traditions, Jhonrey is not limited by them, and he is one of the many emerging young Mindanao artists who are seeing the convergence between abstract expressionism and the island’s ancient visual traditions.

But one thing is consistent in much of his paintings—they make a space feel like home. It is partly thanks to the sepia, ochre, and burnt sienna color scheme of the Talaandig soil paintings. I suspect it is also in large part because these are artworks of an artist who has found joy and peace in building a home, and who now seeks to keep and support this home with his art.

What’s next for Jhonrey?

“Hinabol, they call it,” he told me in a conversation that started with this question. “That is what they call the Talaandig textile. There are still many here in Songco. I want to explore them and draw inspiration from them.” We often chat online while he is traveling with his band, which plays all over Mindanao and sometimes even beyond.

So while he may have plans for his creative direction, the answer to that question is always open. Jhonrey is true to his roots on this island. He is always paying attention to the direction of destiny’s rhythm—the same rhythm that took him out of his difficult past into Songco.

Whatever direction that rhythm may take him, he dances, bringing out the colors of the earth along the way, one footprint at a time.