How to tell the statesman from the politician

Notes from the late President Ferdinand E. Marcos on leadership and the Filipino ideology

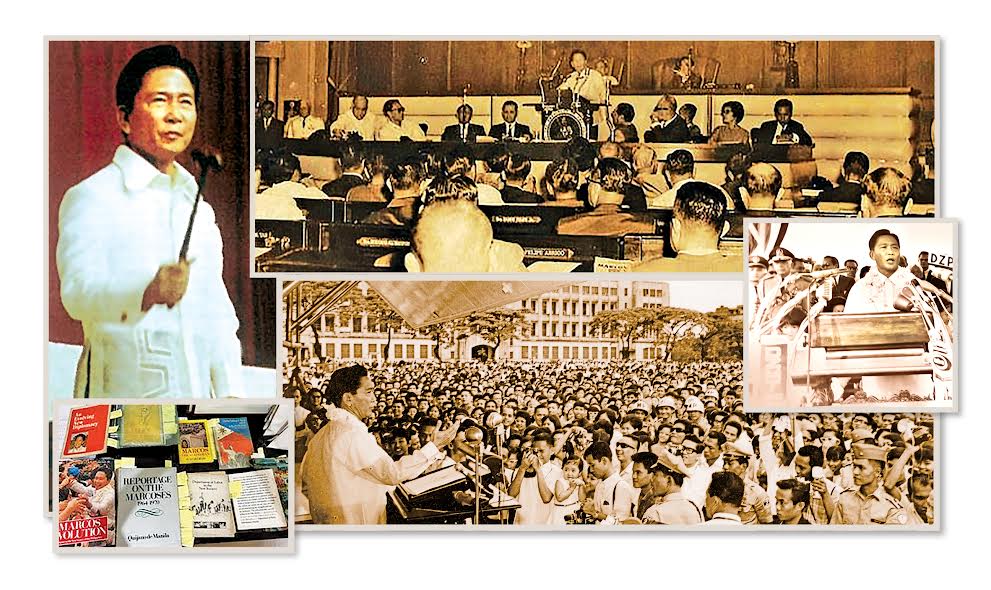

There are times I go through my uncle the late President Ferdinand E. Marcos’ (PFEM) books, speeches, and unpublished manuscripts and see words and even paragraphs that stand out as they resonate with the current political, social, and cultural conditions.

PFEM often looked back to history for guidance and I have grown accustomed to reading his views on certain sectoral issues and how he tackled them when I’m trying to figure out the rationale behind certain paths taken by the current administration.

Lately, the nation has been questioned on what has been perceived as reflective of “shortsightedness” or stop-gap reaction to issues on hand. Gone are the days of statesmen, I suppose, and all we have now are politicians. I am aware of the difference between a statesman and a politician as a concept but I cannot articulate it better than PFEM.

A few days ago, going through another crate of “tambak” papers, receipts, notes, old magazines etc., I chanced upon an unpublished manuscript of PFEM, one of a few. It’s entitled The Filipino Ideology: Philippine Pacific Crisis 1986-87 (second edition), where he illustrated the difference. For his introduction “Our Fighting Faith: The 1986 Philippine Crisis – A New Vietnam or a Third World War,” he wrote:

“Periods of crisis are periods of pragmatism. Such pragmatism can sometimes mean the abandonment of principle, and the celebration of technicism in its worst forms. This is even truer when the crisis is economic in nature and national in scope. The siren songs of exigency and unprincipled pragmatism become exceedingly alluring. They tell us, after all, that solutions are at hand, though these may not be in keeping with our national goals, or with our vision of the future, or even with our outlook as a people. They offer immediate relief not only from the economic difficulties the crisis has created but also from the political pressures that are inevitably brought to bear on leaders who must shoulder the main responsibility of the search for solutions.

A leader who is merely a politician usually bows to the pressures. But no leader who is also a statesman and who is truly concerned for the future of his nation can sacrifice that future for convenient solutions, which can relieve the difficulties, both economic and political, of the present. Such a leader knows that he must strive to solve the crisis while adhering to the principles and ideological considerations. He cannot bargain away the sovereignty that his nation has fought for so long and so bitterly. He cannot trade on the hard-won freedom of action that enables his government to plan and implement policies beneficial to the nation. He cannot surrender to the exigencies of the moment those principles history has shown the nation needs if it is to survive and flourish.

It is more dangerous short-sightedness and form of betrayal, which for monetary solutions, denies the ideological imperatives our history teaches us we need to adhere to unless we want the errors of the past repeated. This short-sightedness—to assume the lesser error—is, however, so prevalent today that we are in danger of being overwhelmed by an outlook that would surrender every principle for exigency. At no other time than now, indeed do we need to recall our ideological moorings: the social, political, and economic principles that together form the basic edifice of the Filipino ideology.”

Just to refresh people’s memory, PFEM believed the Filipino people needed a Filipino ideology that would “serve as the soul and conscience” to bind the country and people. In his book The Filipino Ideology, the late president believed that “no amount of economic progress can have an impact on Filipino society, unless it leaves an indelible imprint on the poor man—not so much in satiating his stomach as in awakening his indifferent soul. For it is one thing to receive benefits and another to derive satisfaction and fulfillment from them.”

To achieve this, PFEM wrote, man should experience “satisfaction and fulfillment from restructuring mental dispositions and evolving an authentic individual and social consciousness that holds priceless the right to freedom, justice, and honor,” something he learned from the brains of the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish colonizer, Apolinario Mabini. Mabini, who called this the “Internal Revolution,” believed that an internal revolution was necessary for the success of an “external revolution.” And it is imperative to point out that the most important field for the internal revolution is “education and culture.”

Sino nga ba tayo (who are we exactly) as a Filipino, as a people, and as a nation? Who were we before the colonizers arrived and when they did colonize us, what did our forefathers fight for or fight against? What was PMEF trying to inculcate in the minds of the Filipinos as did Mabini during the Philippine Revolution of 1896?

A good analogy would be what PFEM tried to teach his children. In his diary entry dated Jan. 9, 1972, PFEM recounted a session with his children about having “roots” or ending up like rolling stones with no direction other than what external factors could provide. At the end of his life, based on the notes and letters he left behind before his death, he urged and prayed for the next generations of Filipinos to “swear to the same persevering faith to take up the majestic cause to shield our people’s freedom, justice, dignity, and honor” even unto death—an honest dream PFEM held close to his heart and lived by for the people of our nation.