COP29 insufficient finance goal threatens global climate action

After two weeks of grueling negotiations, the conclusion of the 29th Session of the Conference of the Parties (COP29) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Baku, Azerbaijan, left developing countries feeling disappointed. While perfection was not expected, hopes for a more ambitious and equitable outcome were high. Climate-vulnerable countries fought tirelessly to replace the outdated $100 billion climate finance goal with a more robust target that would bridge the financial gap and empower vulnerable countries to turn climate ambitions into tangible actions.

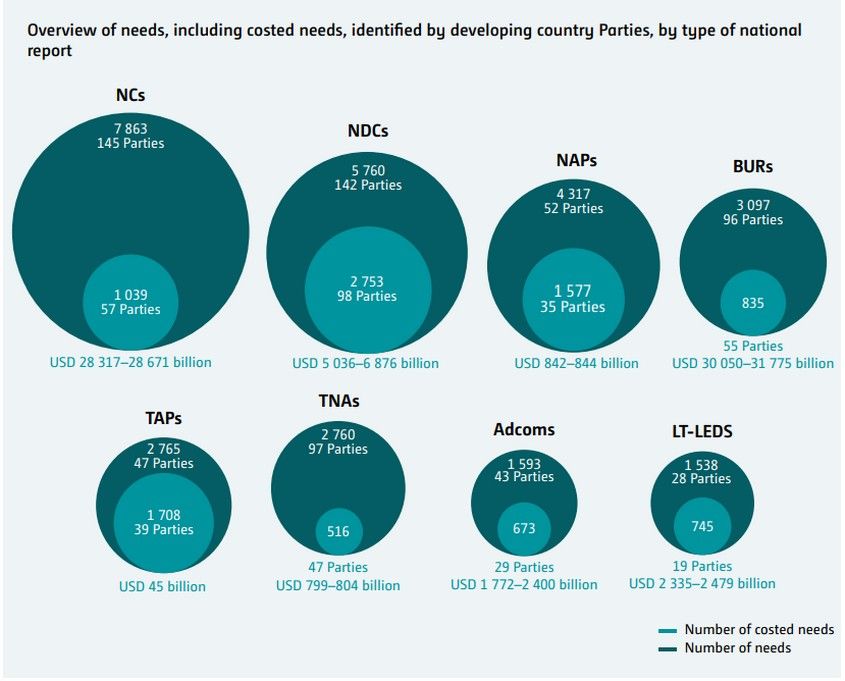

However, the developing world is left with a new climate finance goal of $300 billion annually by 2035. This amount is far beyond what the developing countries demanded in the discussions leading up to COP29. According to a report on the climate finance needs of developing countries by the UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance, developing countries would need more than $5 trillion to implement their adaptation and mitigation measures.

The underwhelming goal is one thing, but the real challenge lies in the provision and mobilization of these financial resources. The experience with the previous climate finance goal shows that developed countries struggled to mobilize the promised $100 billion. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, they only met this target for the first time in 2022, yet this claim remains highly contested by developing nations, as some argue that the target still hasn't been fully met. If this holds true, how much more difficult will it be for developed countries to meet the new $300 billion goal?

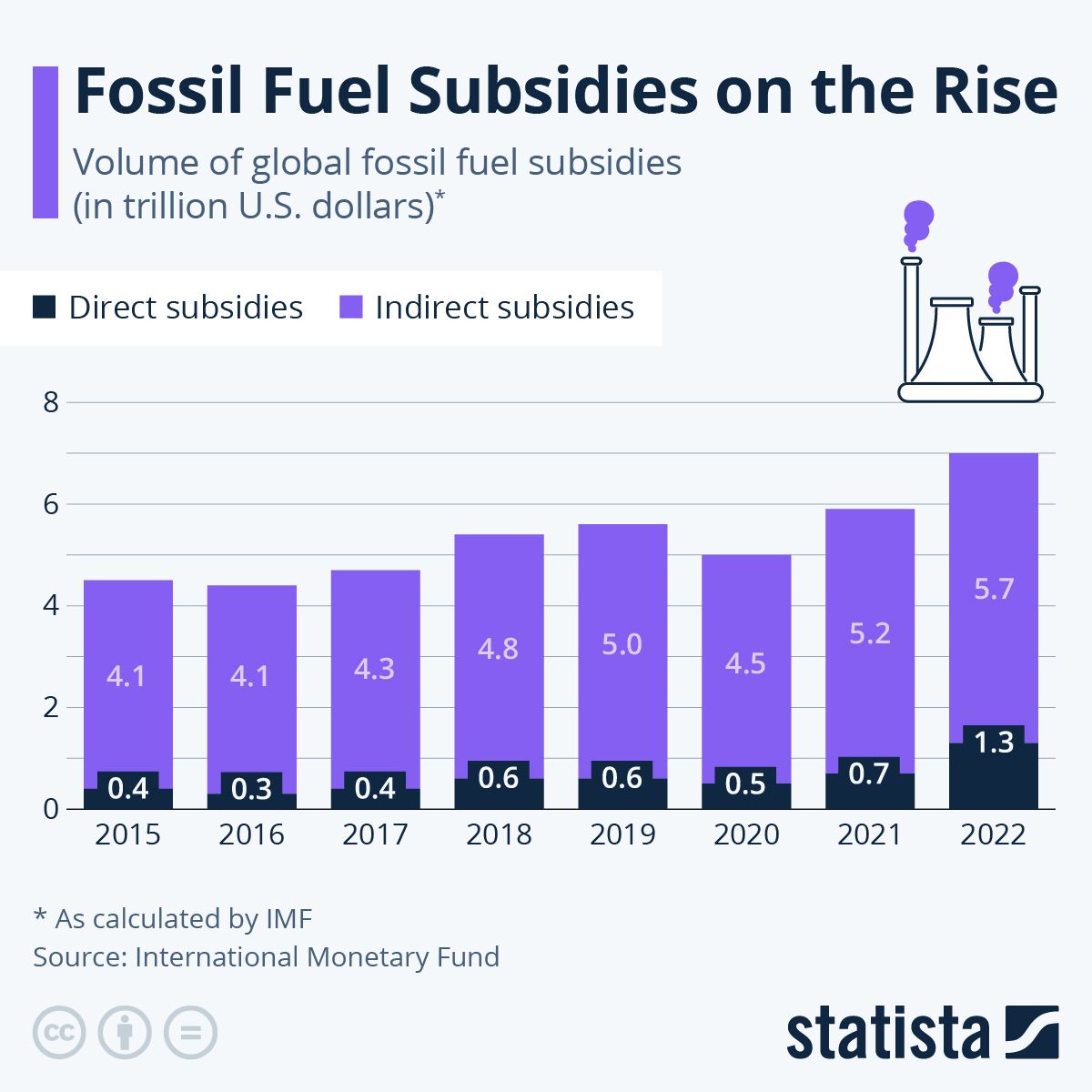

It is important to note that the obstacle is not because there’s not enough finance. There is. In fact, the world is providing an average of $7 trillion of fossil fuel subsidies every year, and countries are willing to spend almost $2.5 trillion to fuel wars. When it comes to activities that further the destruction of the environment or that lead to the loss of lives, property, and identity of people, money seems to be overflowing. This highlights that the real issue isn't resource scarcity, but the failure of the current global financial system to prioritize sustainability and climate action.

Another critical point is that under this new goal, developed countries are not the sole contributors to fulfilling the $300 billion annual goal. The inclusion of private finance as a source of the new finance goal, while seemingly expanding the funding pool, introduces accountability issues as private actors are not bound by international climate agreements. Plus, the new goal mentioned developing countries as contributors in the guise of South-South cooperation. This undermines Article 4, paragraph 3 of the UNFCCC, which clearly mentions that developed countries are responsible for providing “new and additional financial resources” to support developing countries’ implementation of climate plans.

The final COP29 agreement, in all fairness, recognizes the urgent need to reform the multilateral financial system to address the high costs of capital, limited fiscal space, and unsustainable debt levels in vulnerable countries. It also calls for making UNFCCC climate funds more accessible and effective. By incorporating these provisions, the international community sends a clear message: The global financial system must evolve to meet the demands of the climate crisis.

It is also crucial to note that the COP29 decision includes a call on all actors to mobilize efforts to scale up financing to at least $1.3 trillion annually. The "Baku to Belém Roadmap to 1.3T" will guide efforts to achieve this target during next year's climate talks in Brazil. This roadmap must be translated into real, substantial action, and not just empty promises. Otherwise, it would be both unjust and illogical to expect developing countries to craft ambitious plans to combat climate change while continually denying them the fiscal space needed to bring these plans to fruition.

At its core, this so-called finance COP has undeniably fallen short of expectations and reinforced concerns about developed countries’ commitment to climate finance. While negotiators sought to uphold multilateralism, the resulting agreement fails to address the urgent and mounting needs of vulnerable communities. For millions losing their homes to floods or their livelihoods to drought, such compromises feel like empty promises.

Still, we must not allow despair to take root. While climate advocates mourn this setback, our resolve remains unshaken. With billions of lives on the line, we have no choice but to demand a just and sustainable future. The sun must first set before shining light on a new tomorrow. Rest if you must, and when you are ready, we will rise together to rewrite a reality that leaves no one behind.

About the Author: Keith Sigfred Ancheta is a climate advocate, communicator, and stubborn optimist. He is currently working as the Climate Finance Program Officer of The Climate Reality Project Philippines.