At A Glance

- Whether you believe in the aswang or not, the power of these stories is undeniable. They've shaped Capiz's identity, casting a long, dark shadow over the province while also providing a unique glimpse into its rich cultural narrative.

By Jacqueline Lucero

“I’m in Roxas City, Capiz,” I said casually when I picked up my friend’s call. There was a brief pause before she shot back, “Hoy, ingat ka dyan! May aswang dyan (Hey, be careful! There’s an aswang there)!” This reaction is almost automatic—mention Capiz to anyone unfamiliar with the province and you’re bound to elicit a response steeped in caution and curiosity. The idea of the aswang has seeped so deeply into the collective consciousness that it’s the first thing people associate with this charming region.

Intrigued, I couldn’t help but ask the same question when I visited Capiz for the first time, “Is there really an aswang here?” The stories had built up such a chilling reputation over the years, becoming part of the province’s identity and casting a mysterious shadow over its beautiful landscapes.

Once that thought takes root in your mind, your imagination runs wild. Every creak and rustle becomes suspect. On our first night, my companions began “hearing” things—footsteps outside their rooms, noises on their doors—and some hardly managed to sleep. The aswang paranoia was palpable. “Namamahay lang tayo (We’re just adjusting to our surroundings),” I joked, trying to lighten the mood, though I wasn’t immune to the jitters myself. To drown out the unsettling thoughts, I had my own little ritual: I looped an audio book on YouTube, plugged in my earphones, and let the comforting narrative wash over me.

The weather certainly didn’t help. On our second night, a thunderstorm rolled in like a scene from a horror movie, as if, on cue. Lightning split the sky, and a transformer outside our hotel burst with a loud crack, plunging us into darkness. The ambiance was almost too perfect, as if the universe conspired to support the aswang lore.

To delve deeper into the heart of this aswang story, we turned to Ms. Maria Makiling—better known as Airam Miriam Villarin—a true-blue Capizena born and raised in the province. Who better to ask about the origins of such a captivating tale? According to Ms. Villarin, there are three versions of how the aswang legend began.

The first version takes us back to the Spanish colonial era. Villarin shared that the people of Capiz were once afflicted by a rare disease known as dystonia. This condition caused involuntary muscle contractions, twisting people’s bodies into unnatural, zombie-like forms. The Spaniards, encountering this for the first time, were horrified and perceived these afflicted individuals as ghouls rising from their graves. What was a medical mystery to the locals became supernatural terror to the colonizers, igniting the first whispers of aswang.

The second version leads us even further back, to the time of the Datus—pre-colonial warrior leaders who trained late into the night. Understandably, their wives grew frustrated with their husbands returning home at dawn after hours of grueling practice. In jest, the men began to call their wives “Asawang Uwang,” translating to “mad wives.” Over time, as stories were passed down through generations, the term evolved. It transformed “asawang” from an annoyed spouse into something far more sinister… The aswang.

Perhaps the most intriguing version comes from the shadows of World War II. During the Japanese occupation, locals and American forces cleverly employed the aswang legend as a psychological weapon. To instill fear in the enemy, they staged a macabre scene… A dead man’s body was thrown into the river, his innards grotesquely exposed, and rumors spread that he had fallen prey to an aswang. The tactic worked remarkably well, as the terrified Japanese soldiers were spooked by the tales of these creatures. They left Capiz after only three years, a notably short stay compared to other regions in the Philippines.

These narratives not only paint vivid pictures of how the legend of the aswang has evolved but also highlight the interplay between history and myth, humor and horror. These stories aren’t just spooky campfire tales—they're deeply intertwined with the province’s past, serving different purposes throughout the ages.

Back in the present, it’s amusing how these stories still resonate with people today. Hotel housekeeping staff shared that after tourists check out, they often discover garlic—lots of it—tucked under pillows and scattered around rooms, especially near windows and doors. It’s funny how the aswang myth persists, a cultural quirk that endures despite the passage of time.

Whether you believe in the aswang or not, the power of these stories is undeniable. They’ve shaped Capiz's identity, casting a long, dark shadow over the province while also providing a unique glimpse into its rich cultural narrative. The fascination with the aswang has drawn the attention of many scholars, including Dr. Xiao Chua, a prominent historian and educator in the Philippines, who delves into the complexities of these myths and their impact on culture.

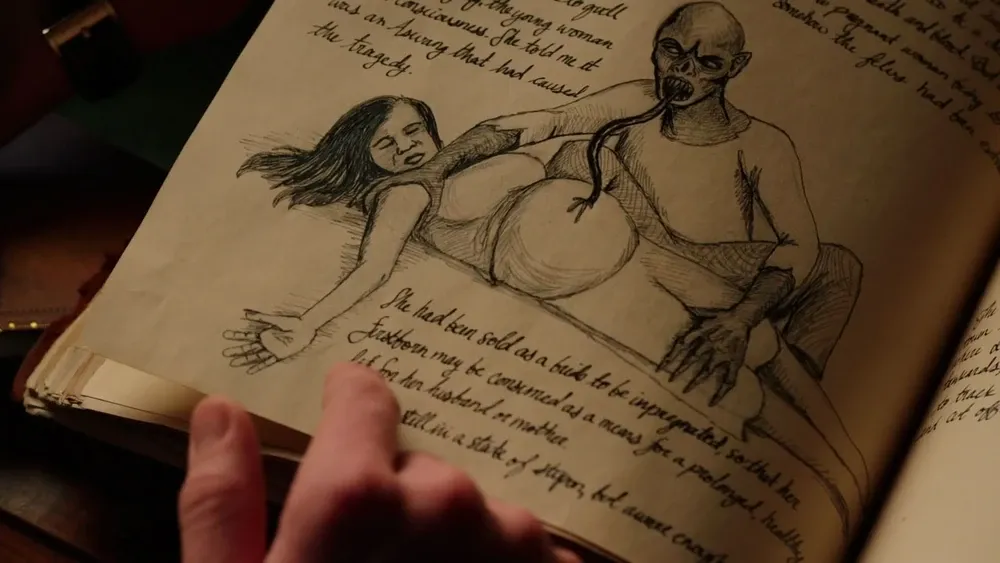

Dr. Chua often explores the rich history of Filipino legends and traditions, including the infamous aswang. This mythical creature, known for its ability to shapeshift and its frightening characteristics, occupies a significant place in the folklore of many Filipino communities. In Capiz, a province famously associated with aswang tales, these stories are woven into the very fabric of local culture and identity.

Typically depicted as a person who transforms into various forms, often at night, to hunt for prey, the aswang embodies both horror and cultural belief. Dr. Chua emphasizes that these legends are more than mere stories; they serve as cautionary tales reflecting societal fears and values.

Academic interest in the aswang extends beyond folklore. Many scholars engage in cultural studies to examine the role of such myths in shaping community identities. These tales are vital narratives contributing to the cultural heritage of Capiz and the broader Filipino identity. By understanding these legends, researchers aim to uncover the historical context and social dynamics that give rise to such beliefs.

Sociologists and anthropologists often investigate how the aswang myth reflects the fears and concerns of local communities. These stories symbolize common anxieties about the unknown and highlight the challenges posed by societal changes. The aswang becomes a mirror through which people can explore their beliefs and the cultural landscape in which they exist.

In literary studies, aswang tales inspire writers to delve into themes of fear and the supernatural. These narratives serve as a rich source of inspiration, allowing authors to explore the beauty and terror of traditional culture. The symbolism inherent in aswang stories resonates with deeper themes of morality, family, and community.

Psychologists have also taken an interest in the aswang and other mythical creatures, using them to explore the psychological aspects of fear and belief in the supernatural. Such studies can reveal how these myths influence mental health and shape individuals’ perceptions of their environment, offering insights into the ways people cope with their anxieties.

Overall, the aswang of Capiz represents a fascinating intersection of myth, culture, and psychology. These legends not only provide a glimpse into the rich cultural heritage of the Philippines but also encourage a deeper understanding of the human experience. As scholars continue to explore the significance of these stories, the aswang remains a powerful symbol of the fears, beliefs, and resilience of the communities that tell them. So, the next time someone asks, “May aswang ba sa Capiz?” you can share these captivating tales and let them decide for themselves.