The Da Vinci Code and how it can help solve climate change

Across three continents, five masterworks and a crucial principle of innovation for the 21st century

At A Glance

- Da Vinci's masterful knowledge of the human vision enabled him to make the <i>Mona Lisa</i> seem to flash a smile when she enters the observer's peripheral vision, but not when she is right at the center of the observer's visual focus.

By Joel Cuello, Ph.D.

The Da Vinci Principle proved transformative in the 16th century—and proves exponentially even more so today in the 21st century.

Leonardo Da Vinci, the polymathic, protean, and archetypal embodiment of the Renaissance man through his genius and prodigiously varied work, straddled disparate branches of knowledge from art and literature to architecture, anatomy, engineering, mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, philosophy, cartography, diplomacy, and more.

And after 500 years since his death, Da Vinci remains the preeminent 21st-century paragon for aptitudinal range.

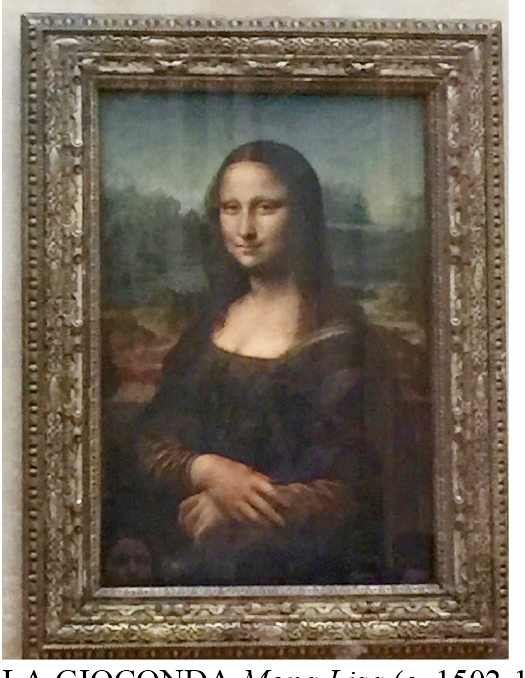

One of Da Vinci’s most celebrated areas of mastery is painting, where his oeuvre includes Virgin of the Rocks (c. 1493), Salvator Mundi (c. 1510), Portrait of a Musician (c. 1487), The Last Supper (c. 1498), and—the crème de la crème of his paintings—the Mona Lisa (c. 1516).

Likely in part because of his myriad interests, Da Vinci managed to produce only some 20 plus paintings in his lifetime or, more precisely, only about 20 plus paintings have been attributed to him, making each one of them all the more prized.

With no deliberate intention on my part, my professional academic travels in the last few years occasioned opportunities for me to view five of Da Vinci’s extant paintings spread across three continents—Europe, Asia (the Middle East), and North America.

At the Louvre Museum in Paris in 2018, I had the chance to study Da Vinci’s Virgin of the Rocks, Saint John the Baptist, and, of course, Mona Lisa as part of the Louvre’s permanent collection in its Peintures Italiennes Wing.

In the United Arab Emirates in 2019, meanwhile, I encountered at the Louvre Abu Dhabi his La Belle Ferronniere, which at the time was on loan from the Louvre Museum in Paris.

And this past October in Washington, D.C., I had a chance meeting at the National Gallery of Art with his Ginevra de’ Benci, the only Da Vinci painting on public display in the Americas.

Witnessing in person the handiworks of the quintessential Renaissance man was at once affirming and instructive.

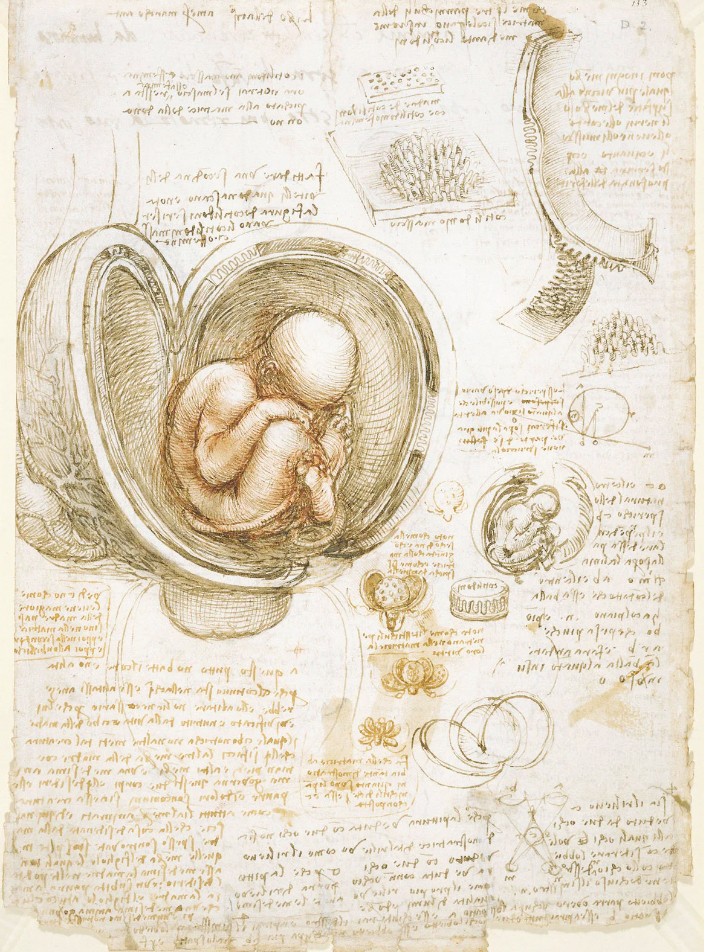

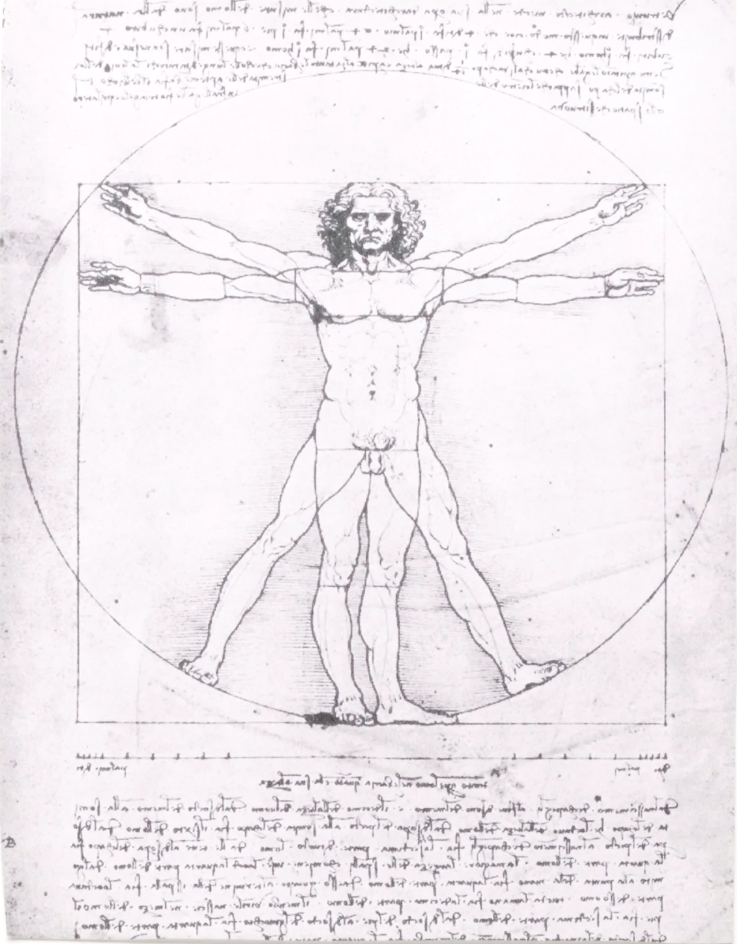

As an artist, certainly ahead of his time, Da Vinci manifestly informed his works with his expertise in other fields, particularly mathematics, architecture, and the then emerging principles of modern science and engineering, in portraying perspective, symmetry, and proportions, among others. He employed, for instance, the mathematical concepts of parallel lines, the horizon line and a vanishing point to conjure the illusion of depth on a flat canvas.

And Da Vinci’s expertise in anatomical drawings and physiology together with his investigations in optics and human vision further led him to pioneer the study of physiognomy by originating the concept of moti mentali in paintings, the depiction of fleeting and momentary mental states, thoughts, and emotions. In his groundbreaking Mona Lisa, the moti mentali concept makes the painting appear to be interactive with the observer.

Da Vinci achieved the foregoing in part through his employment of sfumato, a canonical painting technique of the Renaissance that creates soft transition, as opposed to sharp lines or borders, between areas of light and dark through subtle gradations of color and tones. Further, his masterful knowledge of the human vision, with its focal and peripheral regions, and his apparent understanding of the brain’s ability to fill in the missing details in the fuzzy peripheral image that it perceives enabled him to make the Mona Lisa seem to flash a smile when she enters the observer’s peripheral vision, but not when she is right at the center of the observer’s visual focus, making her image seemingly interactive.

During the Renaissance, Da Vinci was not only the epicenter, but the personification, of the deliberate pulling together and convergence of disparate disciplines of knowledge for the express purpose of creating new value, that is, innovation. Such resultant Da Vinci Principle proved transformative in the 16th century, and proves exponentially even more so today in the 21st century.

As today’s world continues to grow exponentially in complexity, the grand challenges currently impacting humanity and our planet—from climate change to food security to environmental degradation to public health to energy to connectivity and many more—are at once multifaceted and cross-disciplinary, requiring convergent expert knowledge from multiple disciplines to forge the sustainable and resilient solutions needed with great urgency.

Da Vinci himself and his immensely manifold works serve as a clear and present reminder today of our crucial need for an updated approach to curating, assimilating, selecting, and applying knowledge both for solutions-crafting and value-creation, that is, one that is interlinked, cross-boundary, and assiduously connective and integrative.

Louvre Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (April 2019). The author (second from left) was joined by his

then University of Arizona graduate students, from left, Matthew Recsetar, Cody Brown (alumnus),

and Shiwei He

Editor’s note: The author is a professor of Biosystems Engineering at The University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona, corresponding member of the National Academy of Science and Technology of the Philippines (NAST PHL), and past president of the Philippine American Academy of Science and Engineering (PAASE). He lives in Tucson, Arizona. [email protected].