Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and his passion for farming

The output of the agriculture sector was 75 percent in the '60s, now it's at 8.9 percent

At A Glance

- The amount spent buying vegetables and the country's basic staple rice from abroad is a lot of dollars bleeding out of the country, not to mention the fact that we Filipinos have become so dependent on other countries to feed us.

In a few days it will be the 106th birthday of my uncle, the late President Ferdinand E. Marcos. I started this journey of discovery of his life and works quite by accident or was it destiny? After all, his wife Imelda once declared, after trying to figure out for years why our paths continually and almost always serendipitously crossed, “Ah alam ko na (I know)! You will write about my legacy.”

Her explanation is much loftier than mine, which is that I just kept stumbling clumsily on her path. She would go on and on about me writing a book, always telling members of our family that I would write a book about her.

To become an accidental student of the life and works of my uncle, her husband, is a step closer to the fulfillment of this prophecy. This, however, is not the doing of my aunt but by their daughter, Senator Imee Romualdez Marcos. I can see now that Imee shares many traits with her father. She is resolute about ensuring her father’s legacy and salvaging what has not already been addressed, erased, or forgotten.

As an archaeologist and heritage advocate, I have a deep understanding and appreciation of her steely determination to keep the documentation of her parent’s legacy intact. Often, before embarking on a “recovery mission” in one bodega, house, or government institution that might contain documentation of her parents’ works, she would message me a virtual pat on the back and wish me luck. This has been going on since January 2021! We have recovered so much and continue to unearth more to this day but, based on the data I have, I know there is still so much more to recover, consolidate, catalog, and store for easy retrieval. There is knowledge that still needs to be shown to light.

At present, we’ve begun digitizing the speeches of my uncle and aunt from old audio reels from the 1950s to 1986. Some of the speeches were scripted but most were extemporaneous, chockfull of unfiltered thoughts, emotions, and some details that have never been made known to the public. One mystery I uncovered for my dad, as much as for myself, is why my uncle chose the course of agriculture for my dad when he went to study at the University of the Philippines.

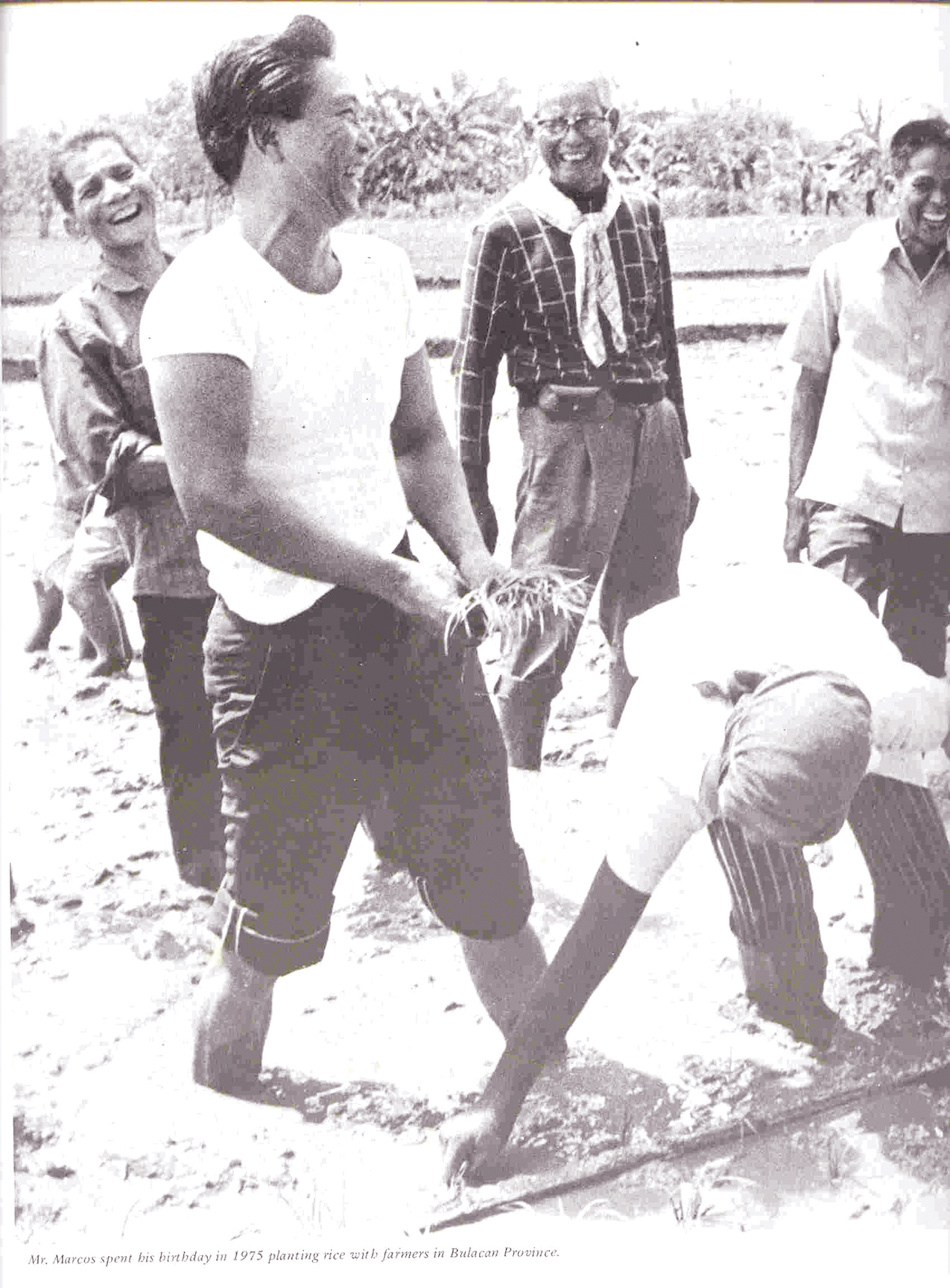

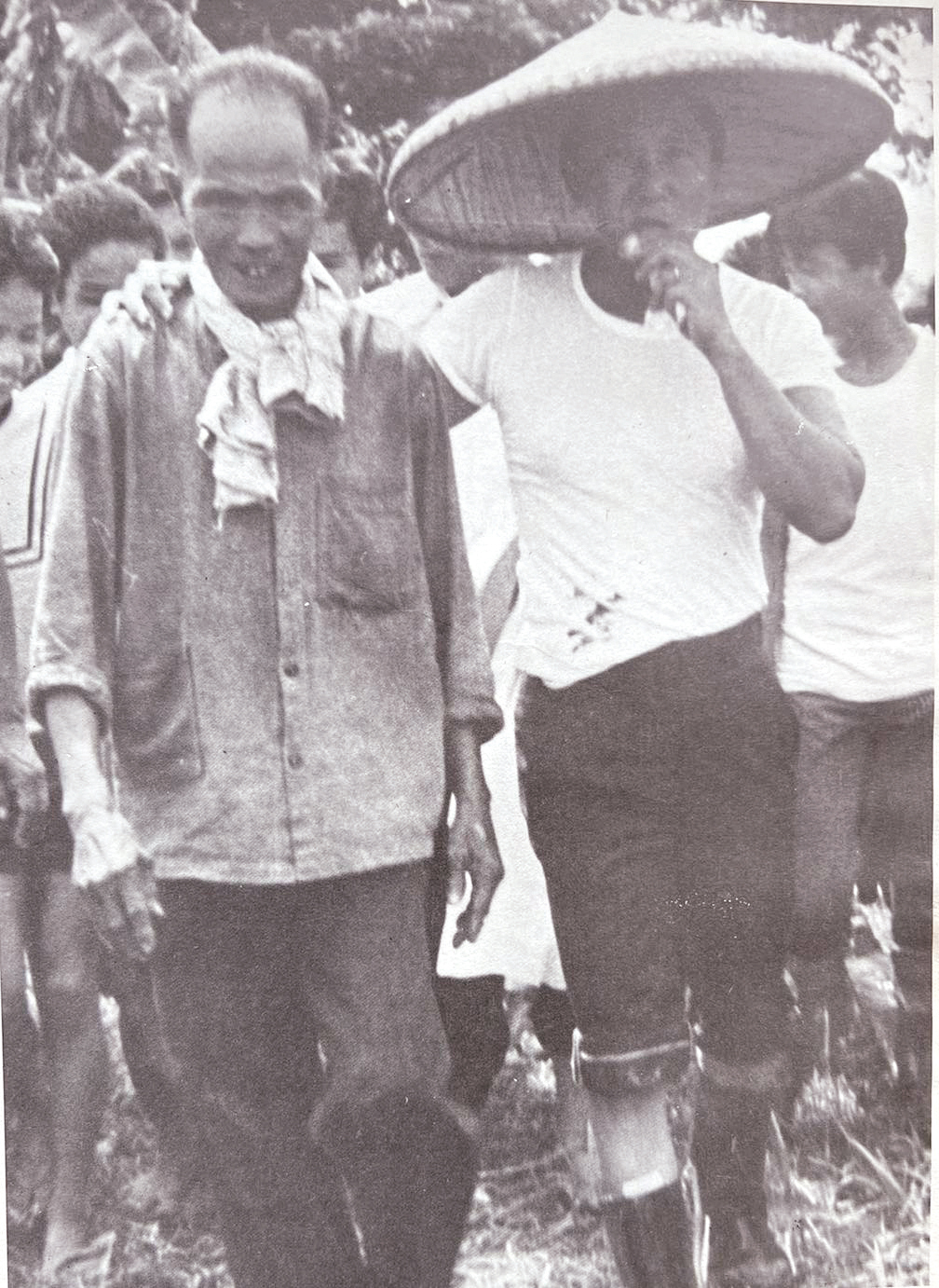

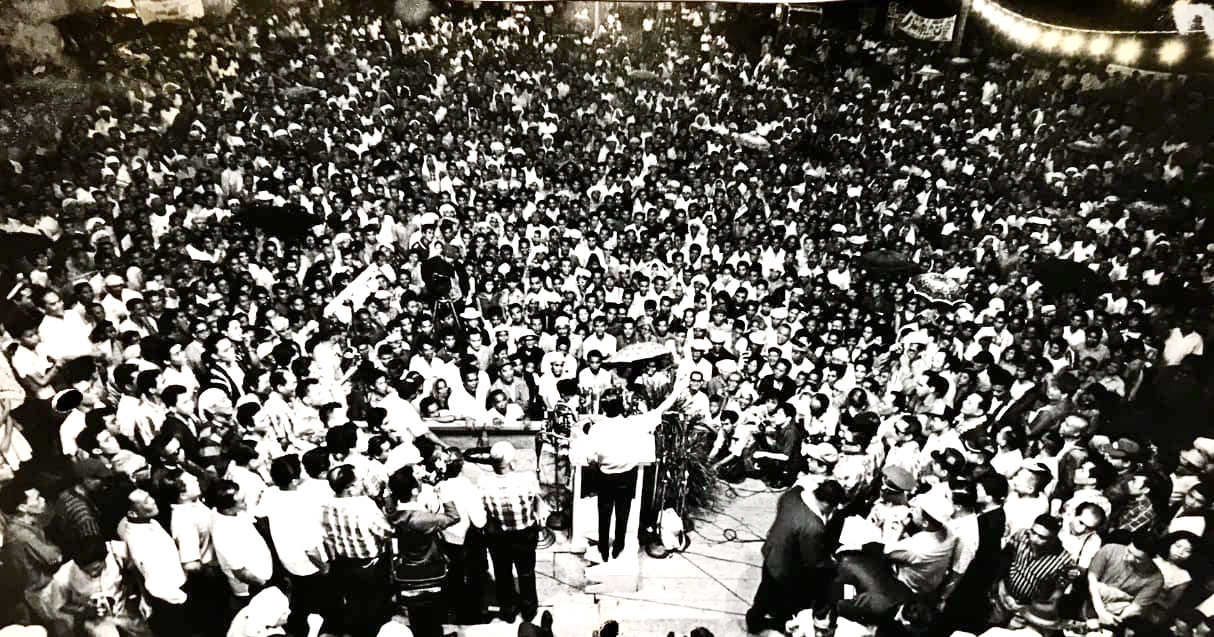

My dad wanted to be a pilot. The second to the youngest in his brood, he was a high school junior when my lolo, his father, died (my lola died when my dad was only three years old). My uncle took him in to live with them, shouldering the burden of sending him to school and getting him started in life. While listening to one recording in a rally in Cebu in 1966, my uncle revealed his kinship with farming after being taught and expected to learn how to till the land at 11 years old by his father, and that his ambition when he was a kid was to study agriculture at the University of the Philippines. Until then, no one knew about this dream of his, aside from his mother, father, and my aunt. He admitted in another speech at the 14th National Rally of the 4H Club on May 18, 1966 that “Every time I am mentally fatigued and physically weak, my mind meanders to the farm, to the farming areas.” My uncle said he had very fond memories of his childhood farming at Barrio Mainitan in Batac, in Sarrat, and in the foothills of the Cordilleras. In fact, when he was little, he was more of a farmer boy than a scholar. My uncle dreamed of retiring with my aunt in “some kind of a farm,” where they could teach their children or even grandchildren the old and pure traits of the farmer.

My uncle said during dark times—giving as an example the time he was in a prison cell awaiting trial for a crime he did not commit just before graduating from law school and when he was a guerilla soldier—he would always fall back on his childhood memories at the farm. As the President of the Republic of the Philippines, his views on farming grew even more elevated, “I take strength and courage from the fact that “the salvation of the Philippines is in the farm.” Of the population, 75 percent was in agriculture at the time. He realized that in the midst of all the big, great, and complicated plans of government—industrialization, mechanization, and drawing up all kinds of technically and expensive socio-economic programs—the government had forgotten that to raise the per capita income of the country, the government should look into raising the per capita income of the farming sector, which then, as now, comprised the vast majority of the population.

According to the International Monetary Fund in 2022, the sectors that contributed to our Gross Domestic Product (GDP) were agriculture at 8.9 percent, industry at 20.7 percent, and services with the biggest contribution at 61.4 percent. The Philippine government defines the services sector as comprised of the “transportation, communication, trade, finance, real estate, private services, and government services sectors.” This sector is considered the main driver of the Philippine economy today.

I must admit, seeing the output of the agriculture sector from 75 percent in the late 1960s to 8.9 percent in 2022, begs the question: Where are we getting our food? As of 2021, World Bank Data showed that the top importers of vegetables to the Philippines were the US, Vietnam, Indonesia, China, and Australia. A 2022 United Nations report showed Philippine imports of vegetables, fruits, and nuts were at $453.45 million. Mung or monggo beans are the biggest cereal import at 50,000 metric tons valued at about $40 million. Monggo is the low-maintenance veggie I know because my dad started planting it.

My dad has this knack for finding things to do with the least amount of work involved for his hobbies. One time, when I visited him in Bicol, he was proudly showing me how it was so easy to grow monggo beans. You just throw the seeds and leave them. After a few months you harvest, although you will need a lot of land to make planting monggo viable since a hectare can only produce a few sacks. The Philippines has also been importing rice. As of 2021, we were holding the title as the second largest importer of rice in the world, importing rice to the tune of $1.42 billion dollars from Vietnam, Burma, Thailand, China, and India.

But I digress. The amount spent buying vegetables and the country’s basic staple, rice, from abroad is a lot of dollars bleeding out of the country, not to mention the fact that we Filipinos have become so dependent on other countries to feed us that we are now at the mercy of market forces outside, which have raised the prices of vegetables astronomically in our markets.

This matter also brings to fore the importance of ensuring our claim to the Kalayaan Group of Islands and upholding our freedom to navigate the South China Sea (SCS), which has now been threatened even more with China’s release of a new official national map this month, laying claim to most of the SCS. The SCS is important because this is where we have the main shipping lanes that lead to our ports to and from the Pacific and Indian Oceans, the Malacca Strait, etc. The Philippines still relies on the sea for the delivery of its food imports and fishing and when the freedom to navigate the sea is restricted, this will serve as a chokehold for the inhabitants of the Philippines.

I know this question has been asked, but let me ask again, “Shouldn’t our dependency on other countries for the most basic of our needs, food, be a matter of national security?”