A migrant story

A look at the waves of foreign migrant workers in the Philippines and the migration of Filipino laborers to the US in the early half of the 20th century

At A Glance

- The Japanese community grew prosperous in Davao to the point Davao became known as Davaokuo or 'Little Tokyo.'

My paternal great-great-grandmother Concepcion Talintin was a tuba drinker.

She enjoyed it very much and believed it was a cure-all. When my great-grandfather Daniel Arcilla Romualdez decided to move his family from Pandacan, Manila to Leyte to nurse his ailing health brought on by consumption (tuberculosis), his mother-in-law Concepcion gave him a prescription of tuba multiple times a day.

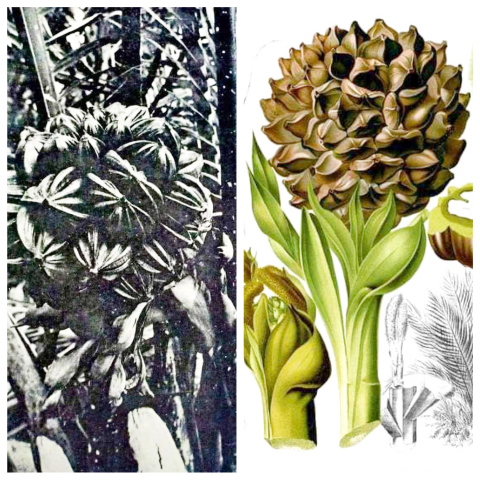

On a recent visit to Roxas City, Capiz, I found out that in the early 1900s, producing over 2,000 barrels a year, the province was one of the top producers of nipa spirits in the country. Records show that the nipa plant has curative and very functional properties. The nipa palm is a plant that keeps on giving. All its parts can be used. The sap, when distilled, becomes tuba or “nipa wine” and, if fermented longer, can be used as vinegar. The water used to boil the nipa palms was used to clean wounds. The leaves, when crushed or chewed, can be applied on centipede bites. When woven, they are used to make roofing for houses. In fact, aside from bamboo, nipa was also favored as a material used in building homes because they grew in abundance in nearby forests at that time.

To know more about the building practices using nipa, I came across a survey conducted by Professor Sato Kan among Japanese laborers based in Davao before the outbreak of World War II. I knew about the waves of migrations to Davao and some parts of Mindanao during the last century and I was aware of the population of Japanese that existed in Davao only in passing but the Sato Survey brought it all back. The survey was conducted among Japanese laborers returning from Davao after war broke out in the Pacific in 1941. The purpose of the survey was to prepare Japan to rule future “colonies,” among them the Philippines.

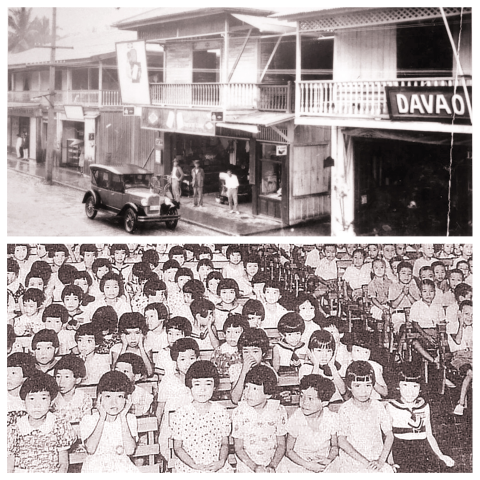

In the early 1900s, the American colonial government took steps to improve the agricultural output of the region by encouraging the establishments of agricultural colonies to be inhabited not only by Filipinos from Luzon and Visayas but other countries as well, like Japan and China. As part of the program, agricultural colonies were established in Zamboanga, Bukidnon, Agusan, and Davao. According to reports, in 1903, the first Japanese contract laborers (180 strong) in Davao was led by Suda Ryosaku. Soon these colonies would house a growing number of laborers working “rubber, copra, and hemp plantations.” The Japanese community grew prosperous in Davao to the point Davao became known as Davaokuo or “Little Tokyo.”

According to historian Teodoro Agoncillo, by the 1930s the Japanese population exceeded the Chinese in the Philippines. Out of a total population of 21,000 Japanese residents in the country, 18,000 resided in Davao. As of 2022 records, there are about 15,000 Japanese residents living in the Philippines today.

While the early half of the 20th century saw waves of foreign migrant workers in the Philippines, we also saw migration of Filipino laborers to the US with the US Immigration Act of 1924. The act allowed citizens of colonies or countries under the jurisdiction of America to work in the US, particularly on the west coast. Soon American farmers’ groups would see this “uncontrolled flood of cheap Asiatic labor,” a majority of whom were Filipino fruit pickers, as a major threat to the local labor force. In fact, The Federation of Labor in America lobbied strongly for Philippine independence after failing to convince the US congress to pass bills curtailing, if not stopping altogether, the influx of Filipino migrant workers into the country.

The Philippines gained independence from America on July 4, 1946. The event has been immortalized in an iconic image taken at Luneta Park with the Philippine flag being raised by newly elected President Manuel A. Roxas while the American flag was slowly being lowered down by then American Ambassador Paul MacNutt. News reports say that the Philippine national anthem was being played in the background. I mentioned this event in a previous article, and I mention it again because, on that trip to Capiz, I was able to visit the Capiz Museum, more formally called “Ang Panublion Museum,” in Roxas City.

The museum is a prime example of adaptive reuse since it was originally the city’s water tank, a circular structure built in 1910. After the city built a modern water system, the old water tank was left unused and forgotten until the city government drew plans to rehabilitate old government structures and create new ones. It was decided to convert the water tank into a “keeper of precious things” in the form of a museum, “Ang Panublion.” Formally opened on April 14, 2012, the museum houses things as precious as archeological artifacts, an ethnographic collection reflecting the cultures of the Indigenous people of Capiz—the Hiligaynon and the Panay Bukidnon—displays on famous Capiznons like National Artist in Music Jovita Fuentes, photographer Jesus Maria Bayot, and President Manuel A. Roxas, among notable others. The Roxas family has loaned their family collection of memorabilia and artifacts to the museum, among them the very flag that was raised on that fateful day in July that marked the beginning of the third Republic of the Philippines.