When was the last time you looked up to a sky full of stars?

Or why we no longer marvel at the sky above us as we once did

At A Glance

- Starlight [is] a real environmental bonus, whose protection and development can allow the existence of different forms of tourism that aim to be just as sustainable.

During the latter part of lockdown, when people were finally allowed to leave their homes and freely walk around the village, I would go out at night, luxuriating in the neon-esque electric blue-colored sky that reminded me of the hues found in paintings of the Mabini Art Movement (1950s to 1970s). As a child I remember being driven along the streets of Ermita. I would be fascinated with these kaleidoscopic pops of color as we drove past the galleries and shops filled with paintings of this popular artform. Artworks of this movement were labeled “cheap art,” catering to tourists and specific clientele whose needs ran toward the decorative versus a finer aesthetic.

In an article, however, University of the Philippines professor Pearl E. Tan explained that the Mabini Art Movement should not be compared to fine art since the “aesthetic standards” of Mabini Art was very different from fine art. The former’s purpose was to make money. Artists of the Mabini Movement painted to earn a living.

On those almost solitary nightly walks with my dog Artemis, I would wish to be able to enjoy these nights longer, knowing life would get back to normal and the colors above me would begin to fade from view, as the lights of the city would begin to outshine the light of the night sky.

Is it wishful thinking to imagine a Philippines with laws that reduce light pollution? Other countries since the 1950s have adopted legislation implementing calibrated measures limiting light pollution (e.g. light haloes from streetlights, etc.). At the beginning, the restrictive measures imposed were for scientific purposes often implemented around observatories or areas of scientific research involving celestial studies.

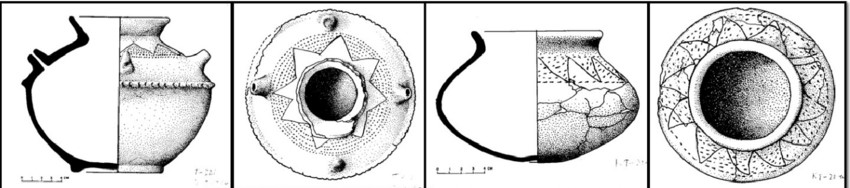

sun motif that can present the argument of importance of celestial bodies in our prehistoric belief systems (Photo Dr. Grace Baretto-Tesoro)

In their paper “Half the Park is Dark,” Bruno Charlier et al pointed out the benefits of “dark night skies.” Expanding its scope and acknowledging its importance, the paper presented “starlight as a real environmental bonus, whose protection and development can allow the existence of different forms of tourism that aim to be just as sustainable.”

There is logic in wanting to protect the dark night skies. “Since the 19th century, history has shown that we have protected areas that can provide us with fresh air, true nature, and wilderness,” which now include our need for “darkness and starlight,” Charlier pointed out. “It wasn’t long ago when the dark sky and the Milky Way were still visible in the urban skies.” Today, as the writer Jacob Hoerger explained, aside from people’s diminished appetite for manned space exploration, “we no longer marvel at the sky above us as we once did, and it has little to do with withered ambitions (for space exploration): the stars themselves are harder to see. That even the brightest constellation Orion can’t compete with the lights of Las Vegas that can be seen from eight different national parks.”

Light pollution has had an impact on various species of animals. Reports show that light from urban areas (skyscrapers, lighthouses, etc.) have caused millions of birth deaths each year and interferes with the navigation of nocturnally migrating birds, turtles (who normally are guided back to sea after laying eggs by the glitter from the water end up in beachfront residential areas). Humans too have been greatly affected causing physical and mental ill-health from long exposure to artificial light.

Good thing to note is that light-policy decisions in various countries around the world are working and have made headway in mitigating “many of the ecological, health, and astronomy-related concerns created by excessive ambient light.” To continue to effect change Night Sky defenders are making a case not only on the basis of light pollution grounded on astronomy or ecology, but on our cultural heritage as well.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has recognized the sky ‘“as an invaluable, natural human resource” in a context where its observation by humans is increasingly threatened by light and air pollution. UNESCO has considered the night sky as an extension of our natural and cultural heritage. At the moment there are 44 dark sky parks and reserves all over the world. This number is expected to increase.

Still on the subject of celestial bodies, one morning I received a message from Mother Maria, an Assumption nun from my childhood, who converted to the Greek orthodox faith decades ago and has since been based in Guatemala. She messaged to share she had just listened to a Russian speak about archeoastronomy and found it very interesting.

Archeoastronomy is the “interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary study of how people in the past understood the phenomena in the sky, how they used these phenomena and what role the sky played in their cultures.” I was fortunate to have visited Mother Maria a few years back during an icon writing program in their monastery.” “While in South America, I had a chance to visit a few Mayan sites and learned of Mayan astronomy in relation to architecture and agriculture. In short, the Mayans used the constellations to tell the passage of time. And based on their visibility or appearance in the sky they knew when to plant or when the season was about to change and how to orient their built structures etc.”

Outside of ethnoarchaeology, we Filipinos do not have much material evidence (built structures or prehistoric agricultural farm lands) to serve as solid proof people in our prehistoric past used astronomy in relation to architecture or agriculture. According to University of the Philippines professor Dr. Victor Paz, in our prehistoric past, other smaller cultural materials reflect a sensitivity to seasons and some sort of calendar for planting or harvesting and arrival of migratory animals. There is evidence, such as recurring design elements in Philippine prehistoric materials like the sunburst (dating back 2,000 years ago), that illustrate some deliberate use of astronomical symbols that could prove people in the past valued the sun (and perhaps other celestial bodies), which they gave a meaningful place in their customs and beliefs system.

On the topic of sunbursts, during proxy duties for my cousin Senator Imee Romualdez Marcos in Capiz on the island of Panay last week, I had the chance to visit the Santa Monica Parish Church or Panay Church. There is a small museum of ecclesiastic furniture, dress, and other historic religious paraphernalia located in the convent beside the church. A burdadero at heart, I made a beeline to the display of church vestments and admired the embroidery work. On the second floor, there was an ongoing exhibit or competition of Marian paintings from artists from all over the region, which was very good too.

What makes Panay Church unique, however, is its claim of holding the largest Catholic bell in the Philippines and the second largest in Asia. It’s called the Dakung Lingganay (big bell). I was fortunate to meet parish cultural heritage and tourism council head Fr. Martin Lex Gevero who toured me around the church and led me five stories up to the belfry in my three-inch wedge heels! There I saw the Dakung Lingganay measuring five feet high and seven feet in diameter. When the bells tolls (the dakung linggay is surrounded by eight smaller bells), they can be heard eight kilometers away. The foundry where the bell was cast is located not far away. Based on church records, the villagers collected 70 sacks of coins to build the bell.

Pan-ay, eight kilometers east of Roxas City, is one of the oldest towns in the Philippines. Founded by the Augustinians in 1581, it was the second Spanish settlement established after Cebu.